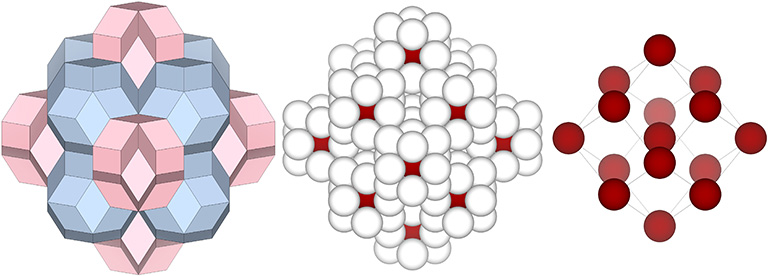

The rhombic triacontahedron has 30 faces, 60 edges, and 32 vertices. Each of its 30 faces is a golden rhombus, i.e., the length of its long diagonal is related to the length of its short diagonal by φ, the golden ratio: (√5+1)/2 ≈ 1.61803398875

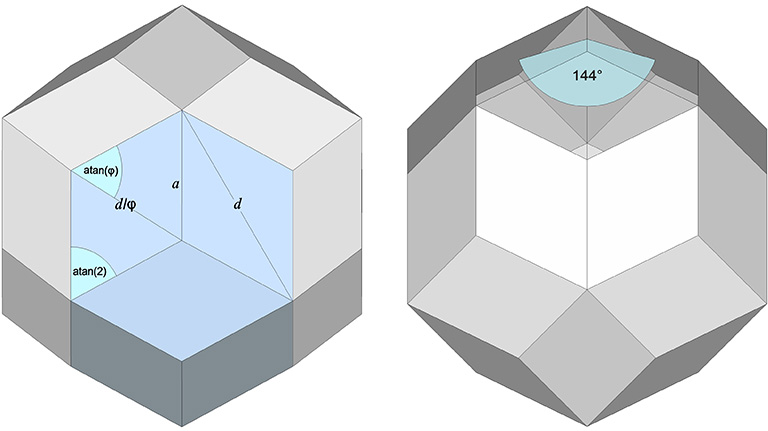

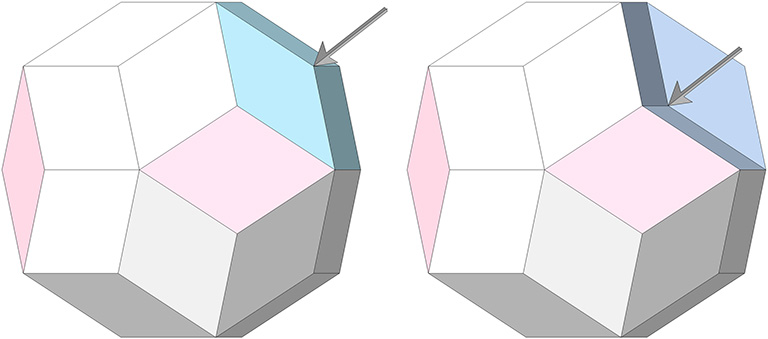

If the long diagonal is taken as d, the length of its short diagonal is d/φ. Its face angles are atan(2) ≈ 63.434948823°, and 2atan(φ) ≈ 116.565051177°. Its dihedral angle is 144°.

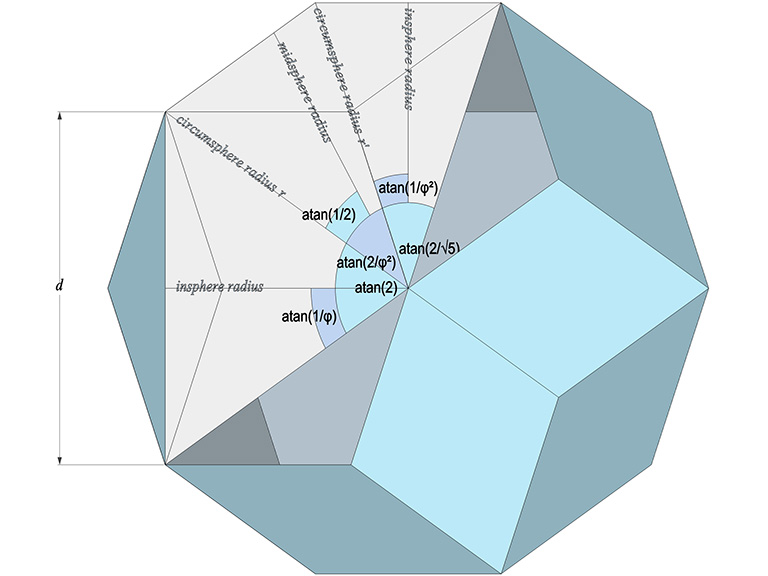

The central angle of its long diagonal, d, is atan(2) ≈ 63.434948823°. The central angle of its short diagonal, d/φ, is atan(2/√5) ≈ 41.810314896°. The central angle of its edge, a, is atan(2/φ²) ≈ 37.377368141°.

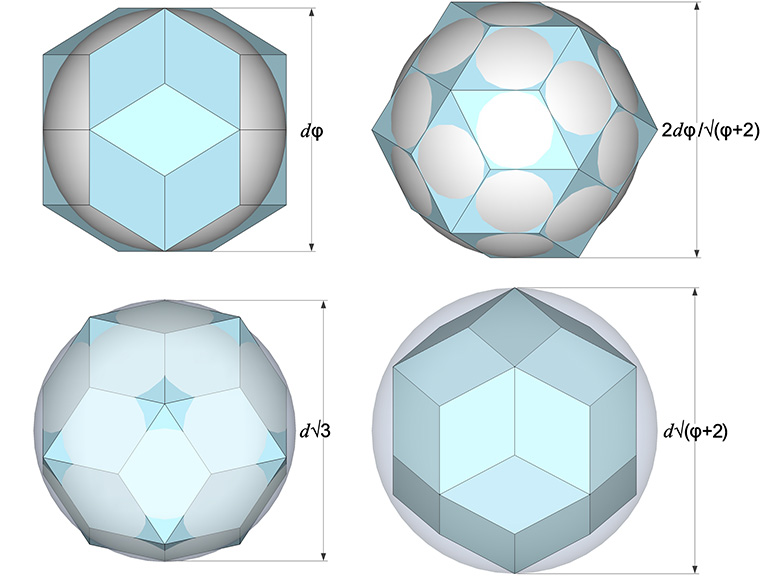

The in-sphere diameter is dφ. The mid-sphere diameter is 2dφ/√(φ+2). The circum-sphere diameter, i.e., the diameter measured by connecting opposite vertices bounded by four rhomboid faces, is d√(φ+2). The diameter measured by connecting opposite vertices bounded by three rhomboid faces, is d√3.

φ = Golden Ratio = (√5+1)/2

Dimensions in units of edge length, a:

- a = edge length

- Volume (cubic) = a³ × 4√(5+2√5)

- Volume (tetrahedral) = a³ × 4√(5+2√5) × 6√2

- In-sphere radius = a × φ²/√(1+φ²) = φ/√(3-φ)

- Circumsphere radius r = a × φ

- Circumsphere radius r‘ = a × φ√(3/(φ+2))

- Mid-sphere radius = a × 2φ/√5

Dimensions in units of the long diagonal, d:

- d = long diagonal

- Volume (cubic) = d³ × 5/2

- Volume (tetrahedral) = d³ × 15√2

- In-sphere radius = d × φ/2

- Circumsphere radius r = d × √(φ+2)/2

- Circumsphere radius r’ = d × √3/2

- Mid-sphere radius = d × 1/√(3-φ)

Identities:

- a = d × √(3-φ)/2

- d = a × 2/√(3-φ)

- d/φ = short diagonal

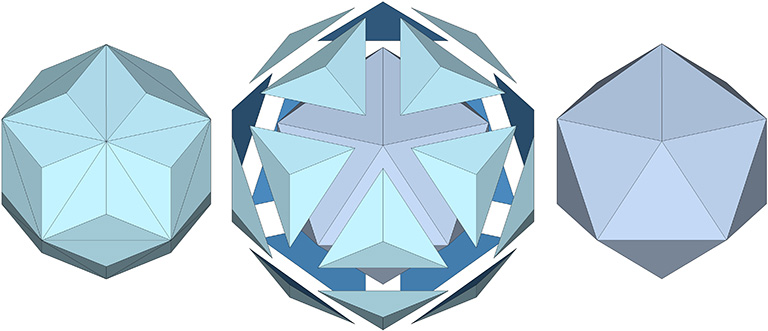

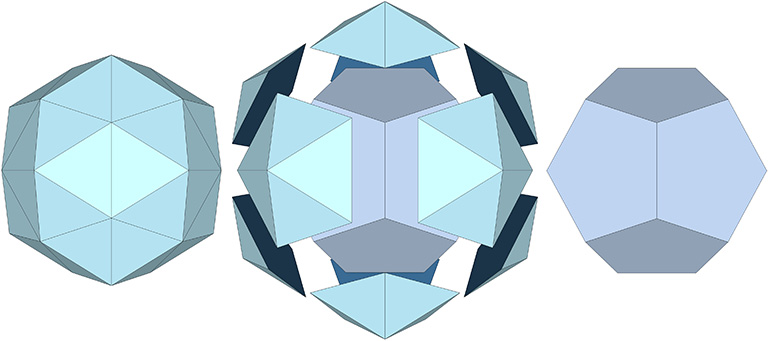

Truncating the rhombic triacontahedron on the long diagonal of its rhomboid face describes the regular icosahedron.

Truncating the rhombic triacontahedron on the short diagonal of its rhomboid face describes the pentagonal dodecahedron.

Connecting the face centers describes the icosidodecahedron.

When a concentrated load is applied radially (toward the center) to any vertex of a polyhedral system, it tends to cause a dimpling effect. As the frequency or complexity of the system increases, the dimpling becomes progressively more localized, and proportionately less force is required to bring it about.

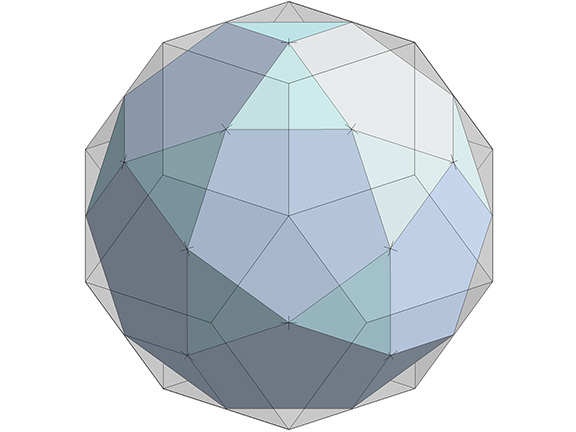

The rhombic triacontahedron may be a limit case in which the dimpling of its eight three-vector vertices produces a concave rhombic triacontahedron that close-packs with the convex triacontahedron to fill all-space.

The convex and concave rhombic triacontahedra close-pack radially around a common center as rhombic dodecahedra, a pattern which is identical to the distribution of unique nuclei in the isotropic vector matrix. (See Formation and Distribution of Nuclei in Radial Close-Packing of Spheres.)

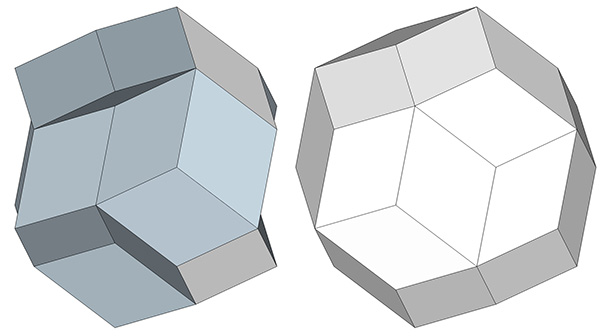

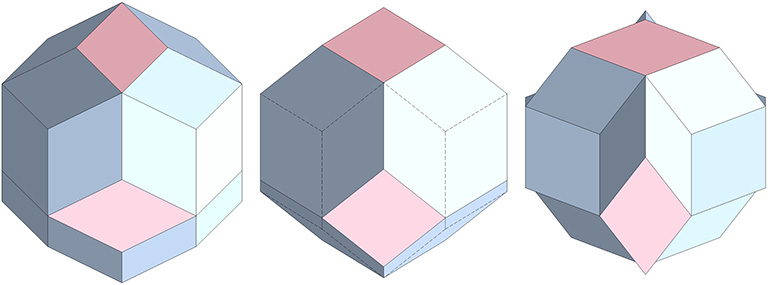

If the edge length is preserved, i.e., if we imagine the rhombic triacontahedron constructed of rigid struts and flexible connectors, it will undergo a jitterbug-like transformation into the all-space-filling Kelvin truncated octahedron at the halfway point in the transition between its convex and concave forms.

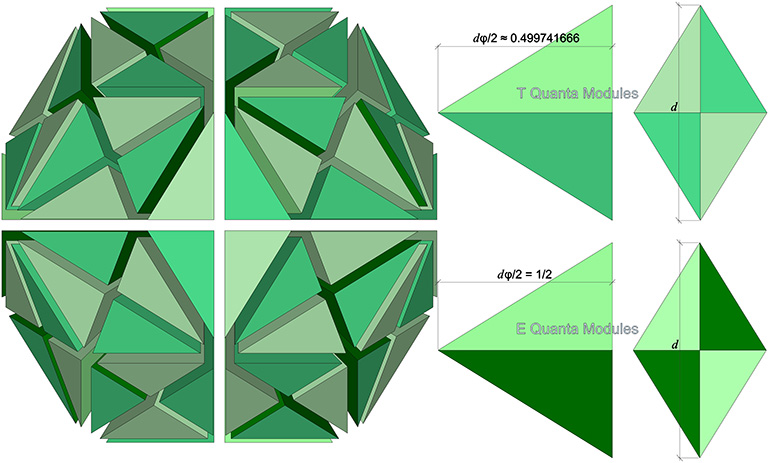

The in-sphere diameter of the rhombic triacontahedron with a tetrahedral volume of 5 is approximately 0.000517 less than the prime unit vector. This is an exquisitely small difference, and Fuller initially believed it to be due to the low resolution of the trigonometry tables he was using. The rhombic triacontahedron can be divided into 120 identical tetrahedra, and with a tetrahedral volume of five, each of the these 120 tetrahedra would have precisely the same volume as the A and B quanta modules, i.e., 1/24th of a unit tetrahedron. These he called the T quanta modules (‘T’ for ‘Triacontahedon’).

Subsequent calculations proved that the rhombic triacontahedron with a unit in-sphere diameter would have a tetrahedral volume of slightly more than 5. So, though his T quanta modules had a rational volume of 1/24th of the unit tetrahedron, the dimension corresponding to the in-sphere radius was awkward and irrational. The quanta module derived from the rhombic dodecahedron with a unit in-sphere diameter was subsequently named the E quanta module (‘E’ for ‘Einstein’). See T and E Quanta Modules.

For a rhombic triacontahedron with a tetrahedral volume of 5:

- 120 T quanta modules

- d = ³√(√2/6)

- In-sphere diameter = dφ ≈ 0.999483332262

For a rhombic triacontahedron with an in-sphere diameter of 1:

- 120 E quanta modules

- d = φ-1

- Volume (tetrahedral) = d³ ×15√2 = (φ-1)³ × 15√2 ≈ 5.007758031333.

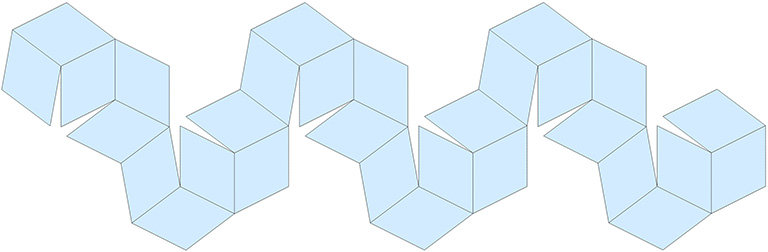

The rhombic triacontahedron may be unspooled into a continuous chain of rhombuses.

The construction is accomplished by 29 sequential folds of 36°.

Hello. It is a a very useful description of the tetrahedron. I particularly enjoyed your animation of a simple way to construct it with paper. Would you please also include how to make it with straws?

Thanks, Esteban. I’m rather proud of having solved that particular paper-folding puzzle. Paper or cardboard is probably the most suitable material for modeling the rhombic tricontahedron. One constructed using sticks and flexible connectors as I describe on my Model Making page would not hold its shape. Without the addition of diagonal bracing, it would just flop around a very unsatisfying way. I have, however, seen tensegrities built with straws and rubber bands, if that’s what you’re thinking of. I recently came across a 60-strut reciprocal tensegrity construction that reduces to either a stable icosahedron with doubled-up struts, or to an *un*stable rhombic triacontahedron. I’ll be sharing that in an upcoming post, if you’re interested.

Yes, I am interested in all you can provide to build straw or dowel models. They teach more mathematics than only the numbers.

I like the rhombic triacontahedron because it is the highest number of equal faces a geodesic sphere can have. Of course, my intention is to stabilize the geodesic sphere by adding shorter straws for the short axis of each rhombus. If you are interested, I can describe the system which I am using to do it.

Sure. I’d be interested in knowing more about what you’re trying to do. And I’m happy to help any way I can. I’ll be posting some new models and instructions soon, and I’ll try to make room for the rhombic triacontahedron. Let’s continue this conversation in email.