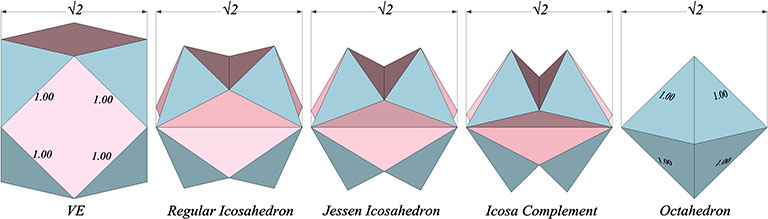

“Transformation of Six-Strut Tensegrity Structures: A six-strut tensegrity tetrahedron can be transformed by changing the distribution and relative lengths of its tension members to the six-strut icosahedron [Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron]. A theoretical three-way coordinate expansion can be envisioned with three parallel pairs of constant-length struts in which a stretching of tension members is permitted as the struts move outwardly from a common center. Starting with a six-strut octahedron, the structure expands outwardly going through the icosahedron phase to the vector-equilibrium phase. When the structure expands beyond the vector equilibrium, the six struts […] lose their structural function (assuming the original distribution of tension and compression members remains unchanged). As the tension members become substantially longer than the struts, the struts tend to approach relative zero and the overall shape of the structure approaches a super octahedron.”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 725.02

Fuller recognized that the six-strut tensegrity structure (which he often referred to as the “tensegrity icosahedron”) and the polyhedron that we are here calling the Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron, was actually a transformation of the tensegrity Tetrahedron. As I’ve said elsewhere, all that can be reasonably called “structure” in the universe is, fundamentally, a self-supporting integrated system of continuous tension and discontinuous compression that Fuller termed, Tensegrity.

The Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron represents the spherical, or what I’m calling the “tensor equilibrium” phase, of the tetrahedron. It occurs at the halfway point in the transformation by which the tetrahedron reverses itself, from its positive (clockwise) to its negative (counter-clockwise) state and vice versa. (See illustration below.) The tetrahedron may be unique in this ability. See Dual Nature of the Tetrahedron.

Approximately midway between its vector-equilibrium phases, the jitterbug describes the regular icosahedron. The collapsing VEs and expanding octahedra, however, do not simultaneously describe the regular icosahedron. The common shape, precisely midway between the transformation from one to the other, is actually the shape of the six-strut tensegrity sphere. This is the “tensor equilibrium” phase of the isotropic vector matrix, in contrast to the more familiar “vector equilibrium” phase.

Fuller neglected to give the shape a name, perhaps failing to appreciate its full significance. Other mathematicians, namely Borge Jessen, have taken credit for its “discovery,” and Wikipedia affirms its identity as the Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron.

Tensor equilibrium is made intuitively obvious with a physical model of the six-strut tensegrity sphere constructed of rigid struts and elastic tendons.** By pulling apart or squeezing together any one pair of opposing struts, the whole structure symmetrically expands and contracts, i.e. “jitterbugs” between the vector equilibrium states of the VE, at maximum separation, and the octahedron, when each strut pair is bunched together. Between these two maximally stressed states is the Jessen orthogonal icosahedron, or six-strut tensegrity sphere, the unstressed state about which the tensegrity oscillates.

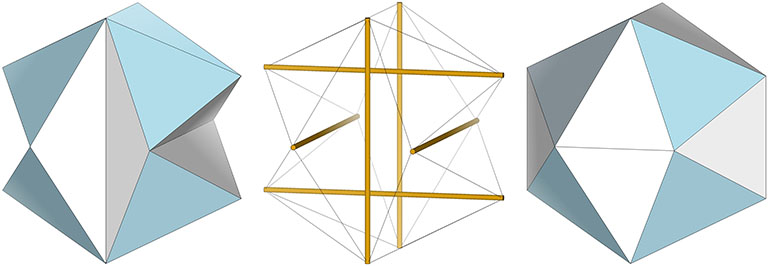

The tensor equilibrium state is also physically and convincingly demonstrated with the models in the following illustration.

The model on the left is the six-strut tensegrity sphere with its continuous web of tension replaced by rubber-band slings. Second from left is a model built with elastic loops stretched between the edges of a cubic scaffold with frictionless rings. Second from right is the conventional model of the six-strut tensegrity sphere. All of these models slip naturally into their equilibrium state which conforms precisely to the shape of the Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron on the far right.

** For detailed instructions for constructing these and other models relevant to Fuller’s geometry, see the page, Model Making, on this web site.

If the long edges of the Jessen’s concave faces are imagined to be the struts of the the six-strut tensegrity sphere, their length would be the square root of two (√2) — the same as the diagonal of the square face of the unit-edge VE and the circumsphere diameter of the unit-edge octahedron. Given a strut length of √2, the Jessen has a rational tetrahedral volume. If the struts are taken to be of unit length, the Jessen has a rational cubic volume.

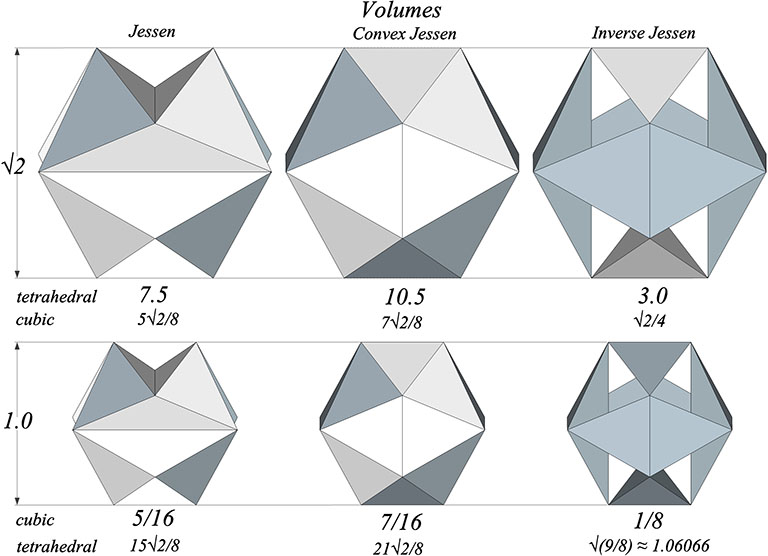

If the strut length (d) is taken to be √2,

- the concave Jessen’s tetrahedral volume is exactly 7.5, and;

- the convex Jessen’s tetrahedral volume is exactly 10.5.

If the strut length (d) is taken to be of unit length (1.00),

- the concave Jessen’s cubic volume is exactly 5/16, and;

- the convex Jessens cubic volume is exactly 7/16.

The polyhedral form of the Jessen can be represented as six irregular tetrahedra occupying the Jessen’s concavities (right column in the above illustration). With the length of their long edge (strut) equal to √2 their combined tetrahedral volume is 3, the same tetrahedral volume as the unit-diagonal cube. With a unit strut length (d=1), their cubic volume is 1/8, and their tetrahedral volume is, significantly, exactly the value of Fuller’s “Synergetics Conversion Constant,” √(9/8), approximately 1.066066. See Pi and the Synergetics Constants.

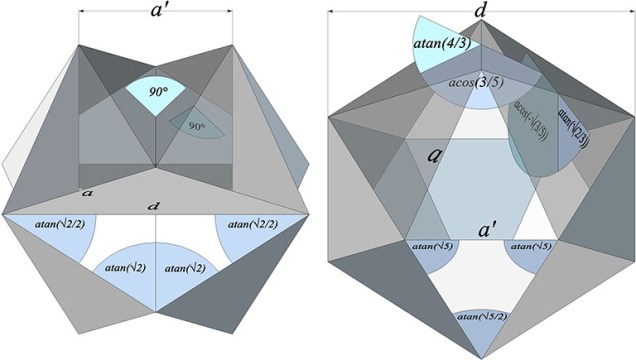

“Orthogonal” refers to the Jessen’s definitive concave form in which its dihedral angles are all 90°; that is, all of the Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron’s faces meet at right angles. In the Jessen’s convex form, the cosine of one dihedral is the second root of the other: acos(-3/5), and; acos(-√(3/5)), which seems somehow significant.

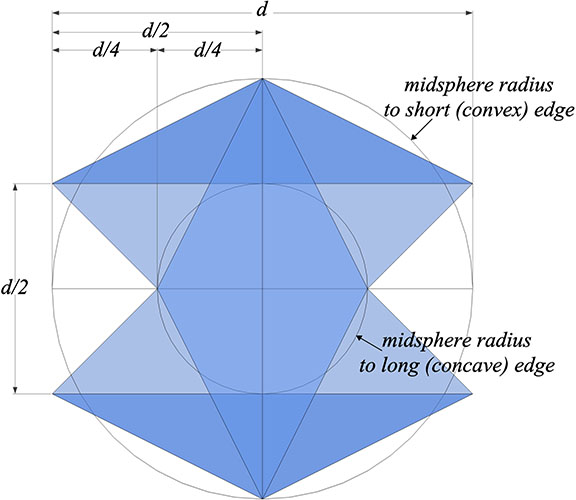

The smallest radius of the Jessen is the midsphere radius to its long (concave) edge, and is exactly 1/4 the strut length, or d/4. In its convex form, the midsphere radius to its short (convex) edge is now doubled to d/2. This may be made more clear in the following illustration:

All the other radii are irrational with respect to both the edge length (a) and strut length (d).

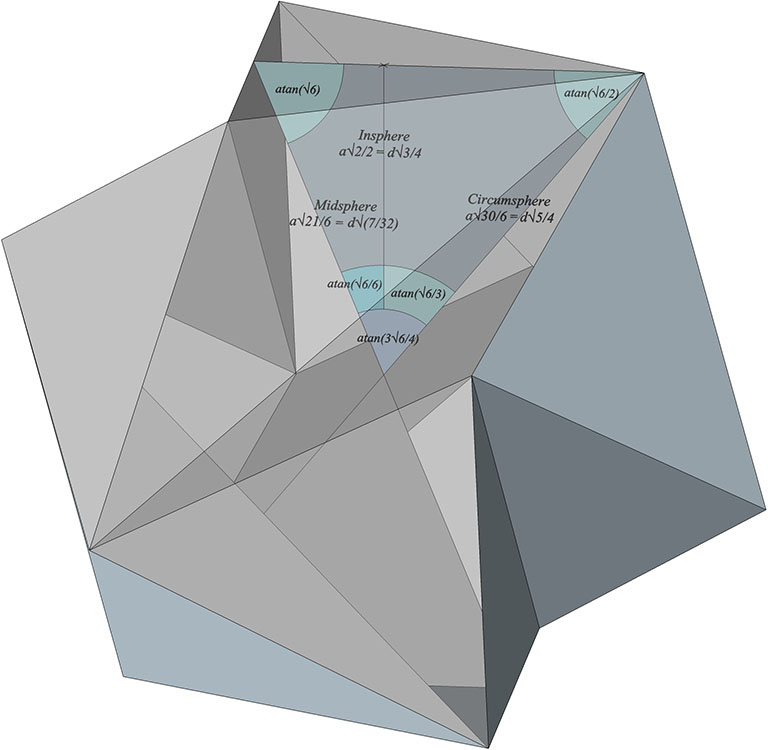

The Jessen’s circumsphere radius and the midsphere radius to its edge (a) forms a triangle of atan(√6), atan(√6/2), and atan(3√6/4). The insphere radius divides the latter angle into atan(√6/6) and atan(√6/3).

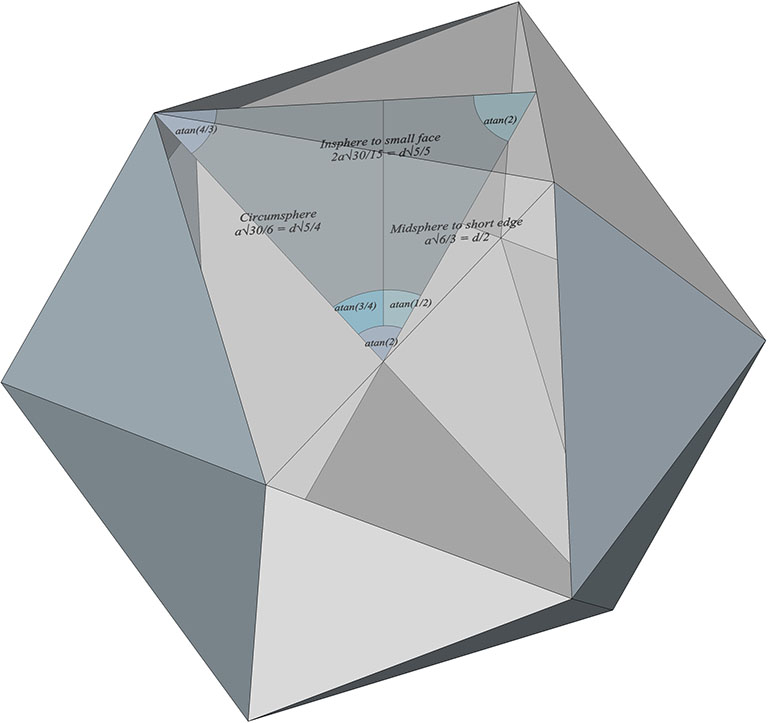

The Jessen’s circumsphere radius and the midsphere radius to its short (convex) edge (a’) forms an isosceles with rational trigonometry: atan(2), atan(4/3), and atan(2). The insphere radius divides the latter angle into atan(1/2) and atan(3/4).

The dimensions of the Jessen relative to its tendon (aka edge) length (a), and its strut (aka long edge) length (d) are provided below:

a = edge (tendon) length

a’ = short edge length of convex face

d = long edge (strut) length

d = a × 2√6/3

a = d × √6/4

a’ = a × √6/3 = d × 1/2

Insphere radius = a × √2/2 = d × √3/4

Insphere radius to small face = a × 2√30/15 = d × √5/5

Midsphere radius = a × √21/6 = d × √14/8

Midsphere radius to short edge of convex face = a × √6/3 = d × 1/2

Midsphere radius to long edge of concave face = a × √6/6 = d × 1/4

Circumsphere radius = a × √30/6 = d × √5/4

Face angles (convex): atan(√5/2), atan(√5/2), atan(√5)

Face angles (concave): atan(√2/2), atan(√2/2), acos(-1/3)

Dihedral angles (convex form): acos(-3/5); acos(-√(3/5))

Dihedral angles: all 90°

Cubic Volume (concave form) = a³ × 5√6/9 = d³ × 5/16

Tetrahedral Volume (concave form) = a³× 20√3/3 = d³ × 15√2/8

Cubic Volume (convex form) = a³ × 7√6/9 = d³ × 7/16

Tetrahedral Volume (convex form) = a³× 28√3/3 = d³ × 21√2/8

As noted earlier, the Jessen has rational cubic volume of 5/16 when the strut length (long edge) is of unit length; the Jessen has a rational tetrahedral volume of 7.5 when the strut length (long edge) preserves its length at vector equilibrium, i.e. √2. This is a gratifying result, and reinforces my view that the Jessen models an equilibrium phase of the isotropic vector matrix.

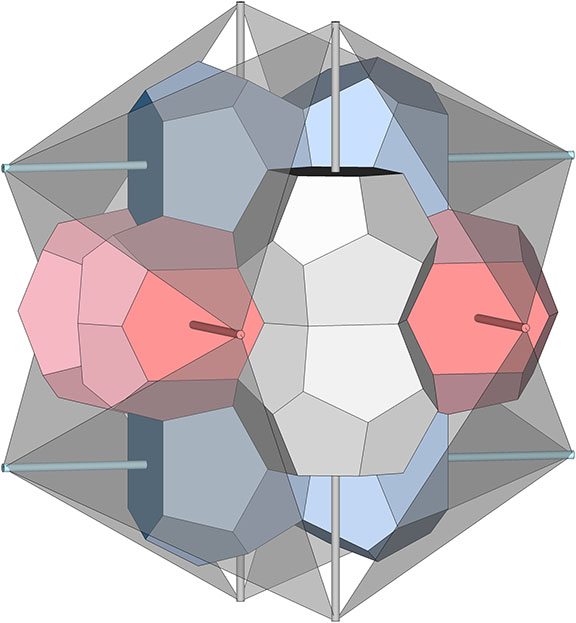

The Jessen icosahedron is a truncation of the pyritohedron.

The struts (or long edges of the concave faces) of the Jessen align with the tetrakaidecahedra of the Weaire-Phelan matrix. (See: Tetrakaidecahedron and Pyritohedron.)

These and other clues seem to point to a relationship between the tetrakaidecahedron-pyritohedron matrix (aka, the Weaire-Phelan structure) and tensor equilibrium, in addition to the relationship between the close packing of the voids in foam matrices with the close-packing of spheres and the distribution of nuclei in the isotropic vector matrix.