“Vector equilibrium accommodates all the inter-transformings of any one tetrahedron by polar pumping, or turning itself inside out. Each vector equilibrium has four directions in which it could turn inside out. It uses all four of them through the vector equilibrium’s common center and generates eight tetrahedra. The vector equilibrium is a tetrahedron exploding itself, turning itself inside out in four possible directions. So we get eight: inside and outside in four directions. The vector equilibrium is all eight of the potentials.”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 441.02

The axes of the set of 4 great circles of the vector equilibrium (VE) stands apart from the other three sets in its significance to the rest of Fuller’s geometry:

- It is the axis on which the vector model rotates and contracts in the jitterbug transformation. (See: Jitterbug.)

- Each of its four great circles passes through six of the twelve points of tangency between radially close-packed spheres, making it the most versatile of what Fuller called “railroad tracks of energy” in the isotropic vector matrix. (See: Great Circles: The 25 Great Circles of the Vector Equilibrium (VE); and The 25 Great Circles of the VE (new illustrations).)

- It is the only axis that connects nuclei directly to other nuclei, and forms the 14-around-1 rhombic dodecahedra matrix on which nuclei are distributed. (See: Formation and Distribution of Nuclei in Radial Close-Packing of Spheres.)

- It is the only axis along which no single great circle route can be directly traced. (See: Inter-Sphere Connections via the 25 Great Circles of the VE.)

- Its four great circles define the spherical vector equilibrium.

- The combined area of its four great circle planes is identical with the surface area of the sphere of the same radius.

- The axis forms a channel for the polar pump model of the jitterbug transformation, which is the topic of this article.

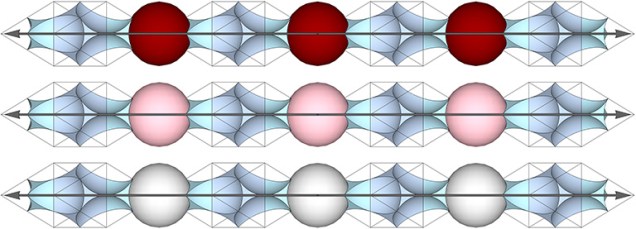

The primary axis of the set of four great circles directly connects each nucleus with 8 of its 14 surrounding nuclei with no intervening spheres between them. Its secondary axes also connect like spheres: nuclear voids with nuclear voids, and; F1 shell spheres with F1 shell spheres. (See: Categories of Spheres in the Isotropic Vector Matrix: Nuclei, F1 Shells, and “Nuclear Voids”). Each sphere is separated along each axis by interstitial space consisting of one concave VE and two concave octahedra. (See: Spaces and Spheres (Redux) and Spheres and Spaces.)

If we imagine the matrix shuttling spheres exclusively along these axes, each cycle of the jitterbug produces identical results and no change is perceived in the configuration or orientation of the discrete cubes and VEs described in my previous article, Blinkers, the Jitterbug, and the “Crystalized” Isotropic Vector Matrix.

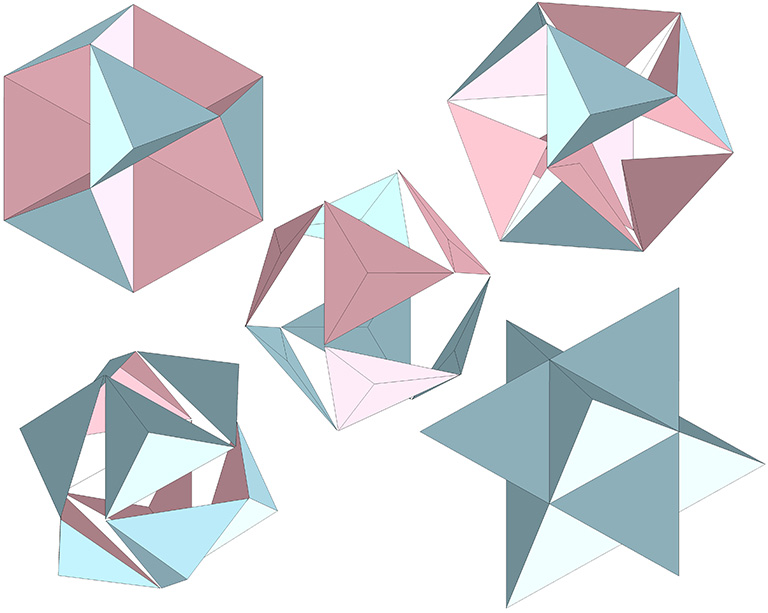

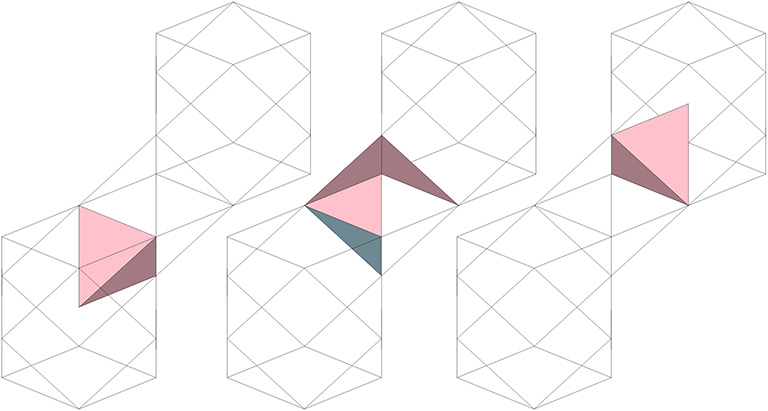

The jitterbug is, essentially, the positive-negative oscillation of tetrahedra, and Fuller consistently viewed this oscillation as the vector equilibrium (VE) exploding itself, its eight tetrahedra forcing their common vertex out through their opposite faces to form the star octahedron, or cube, as illustrated below.

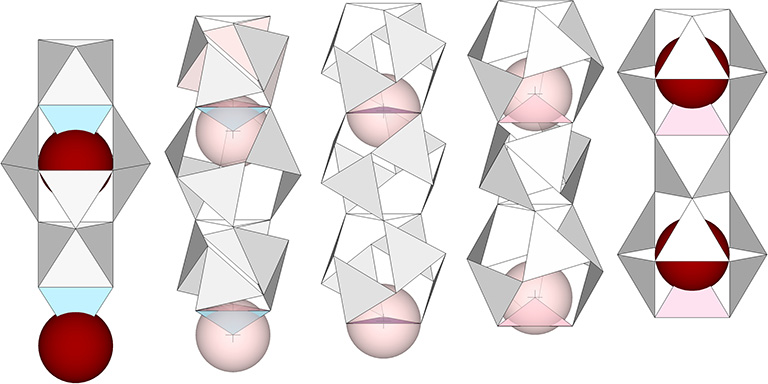

The following illustrates how this model of the jitterbug might be conceived as the shuttling of nuclei into and out of the octahedra as they unfold into VEs and fold back again into octahedra. This is the same space-to-sphere, sphere-to-space oscillation as in all other models of the jitterbug—the only difference being the axis along which the adjacent space (the concave VE that is replaced by a sphere) is perceived to lie.

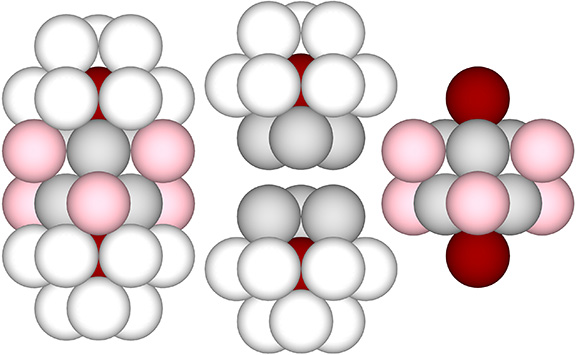

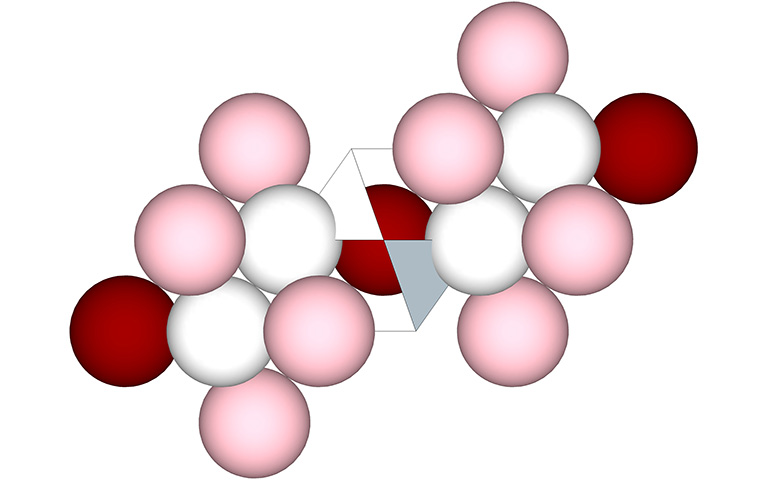

In the illustration below, the six spheres of the octahedron (gray spheres) contribute 3-spheres each to the F1 shells of two nuclei (center) aligned on opposing points of each of the cube’s (right) four diagonals, one of which is the primary axis of the four great circles connecting nuclei (red spheres), and the others are secondary axes connecting nuclear voids (pink spheres). This polarization of the nuclei to just one of the four axes may explain why Fuller referred to its migration along this axis as a “polar” pump.

In the following illustration, two of these polarized cubes are shown straddling a VE with which they share a nucleus.

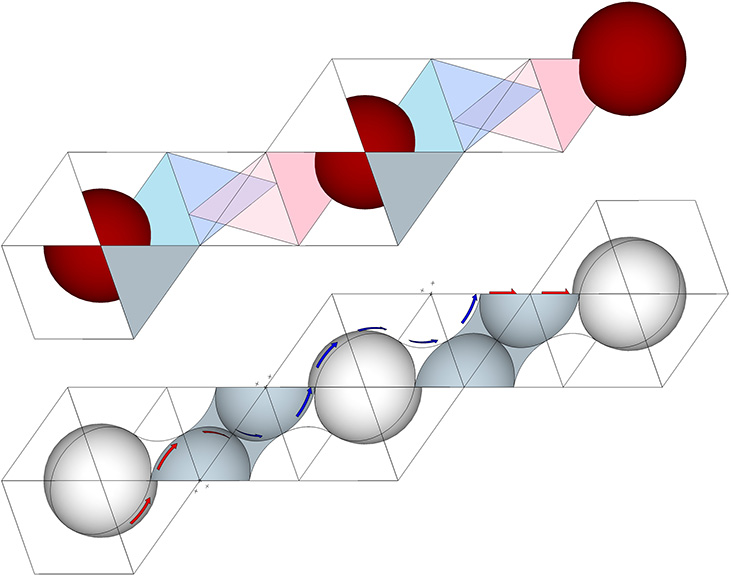

At the top of the illustration below, the cubic clusters of close-packed spheres have been replaced with octahedra, inside of which are the inside-outed tetrahedra from their adjacent VEs. Below that, the octahedra and tetrahedra have been replaced with concave VE spaces and concave octahedron interstices. Arrows indicate how the set of four great circles constitute the shortest-distance geodesics connecting spheres along the axis. Note that the path makes a sharp right angle at the halfway point. For each of the eight possible geodesics (for which only one is shown), the red arrows change to blue arrows at the point of tangency between two of the six spheres of the octahedron that sits between the VEs. This mirrors the positive-negative oscillations of tetrahedra.

Another way of looking that this is to have the tetrahedra unfold and wrap themselves around the octahedra, then unwrap and refold themselves into tetrahedra at the octahedron’s opposite pole.

Click to view animation under a separate tab.

The octahedron sits between a positive and a negative tetrahedron in the isotropic vector matrix, and accommodates their inside-outing, or positive-negative oscillations, both internally, i.e., as inside-outed tetrahedra clustered inside the octahedron, and externally, i.e., as tetrahedra unfolded and wrapped around its surface. The model provides a way of visualizing the jitterbug transformation on an otherwise fixed matrix.