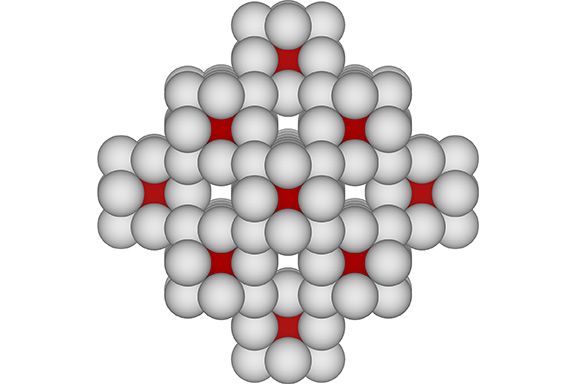

“The first layer consists of 12 spheres tangentially surrounding a nuclear sphere; the second omnisurrounding tangential layer consists of 42 spheres; the third 92, and the order of successively enclosing layers will be 162 spheres, 252 spheres, and so forth. Each layer has an excess of two diametrically positioned spheres which describe the successive poles of the 25 alternative neutral axes of spin of the nuclear group.”

— R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 222.23

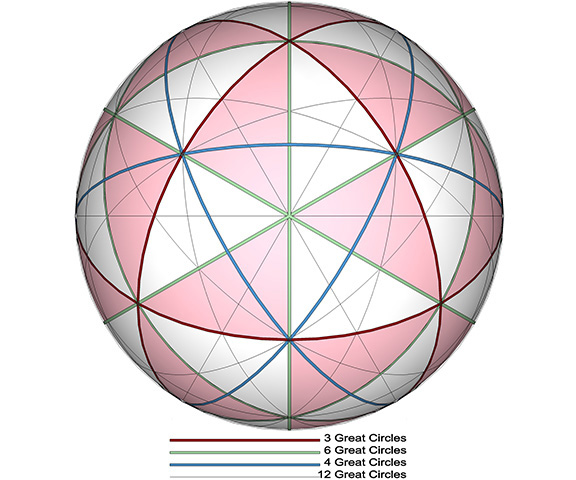

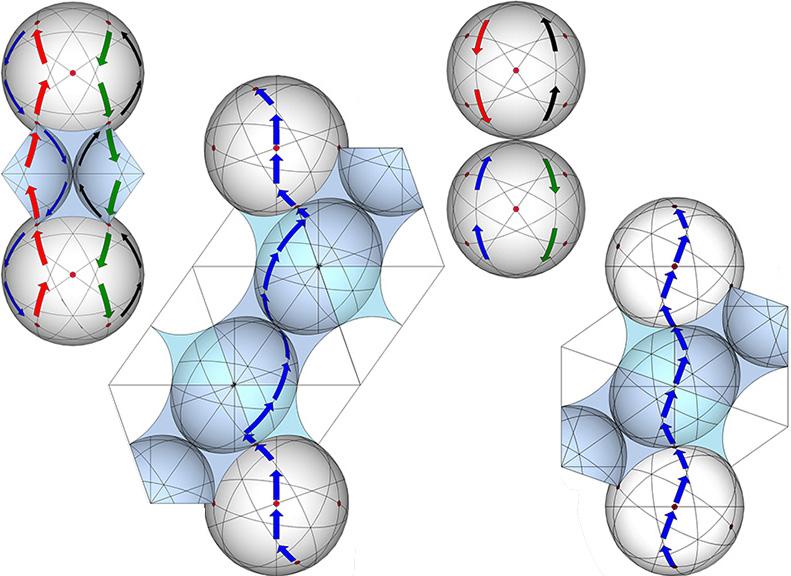

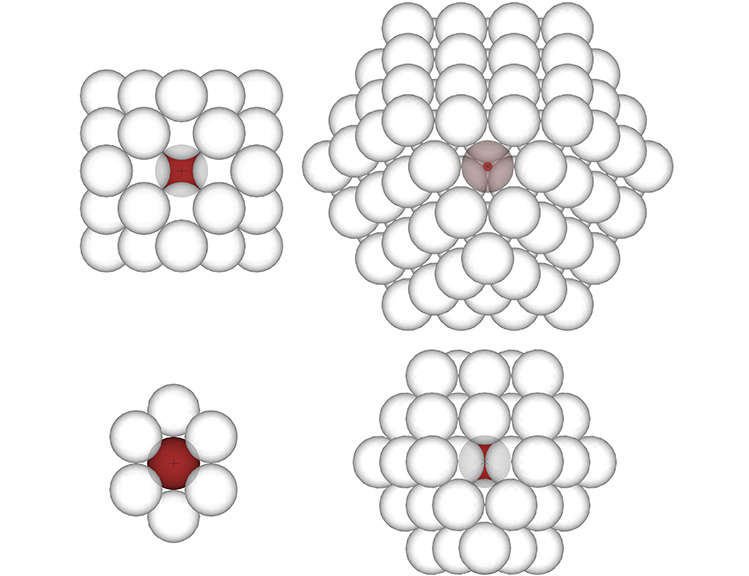

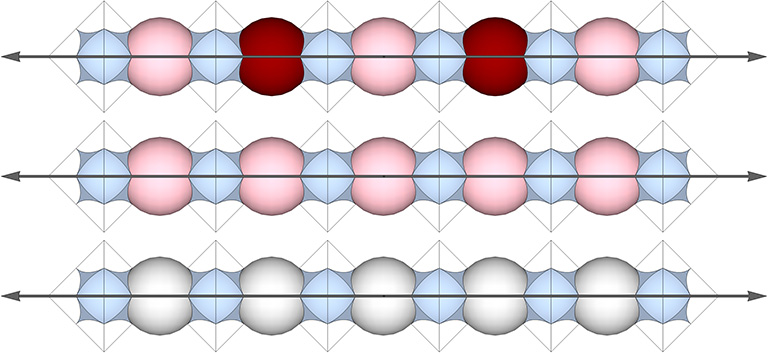

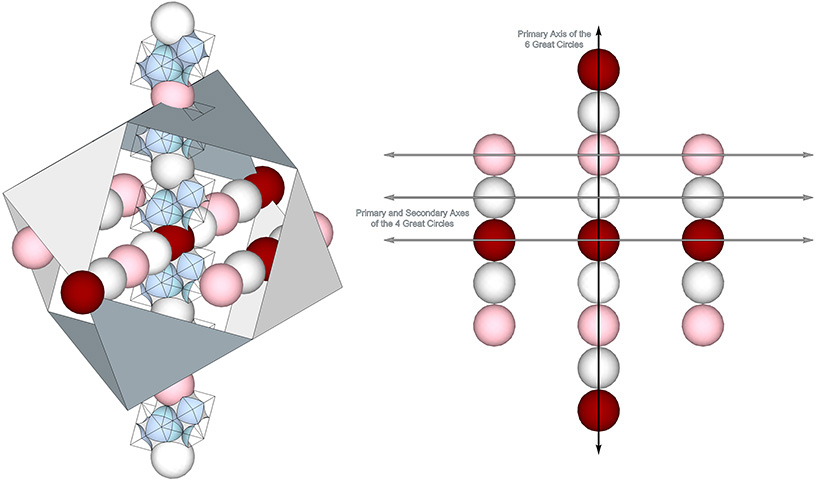

The four sets of 3, 4, 6, and 12 axes that define the 25 great circles of the vector equilibrium also comprise all line-of-sight connections between spheres radially close-packed in the isotropic vector matrix. That is, each axis proceeds directly, without deviation, through interstitial space from one sphere center to the next. This may be made more clear with the following illustration.

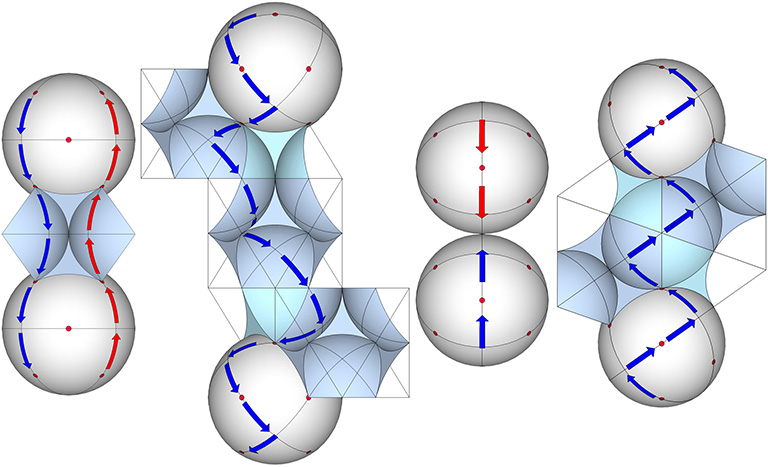

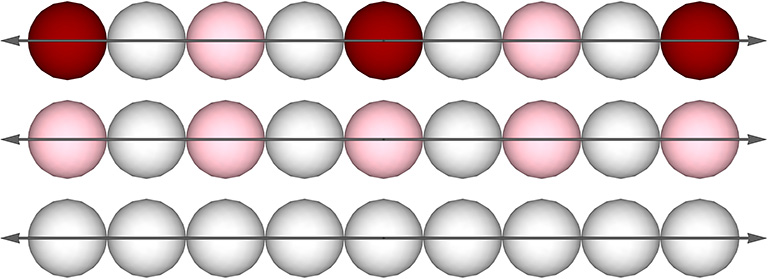

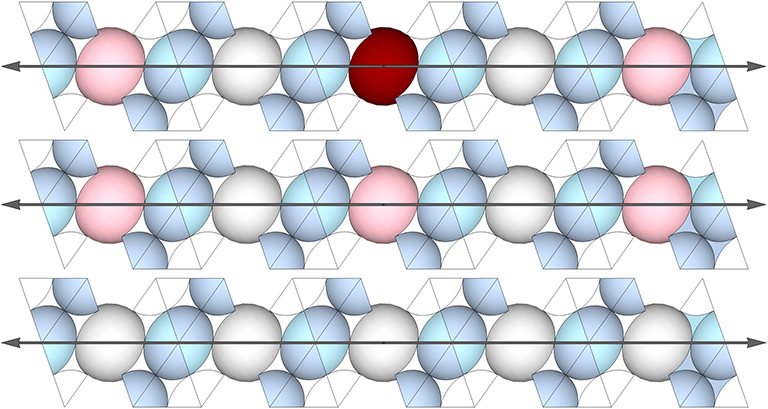

In the above illustration,

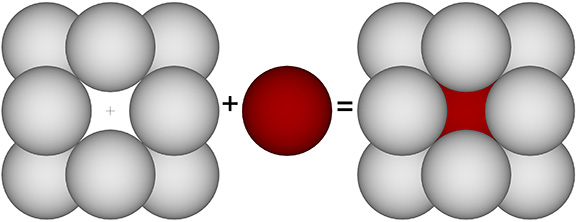

- The axis for the 3 great circles (top left) connects the semi-transparent sphere in the F2 layer with the nucleus (red), having passed through interstitial space in the F1 layer. Note that this is the only axis that provides a direct connection between nuclei and nuclear voids (see Categories of Spheres in the Isotropic Vector Matrix: Nuclei, F1 Shells, and “Nuclear Voids”). The semi-transparent sphere in the F2 layer will be surrounded by the F1 shells of its surrounding nuclei, and therefore qualifies as a nuclear void.

- The axis of the 4 great circles (top right) connects the semi-transparent sphere in the F3 layer with the nucleus (red) after having passed through interstitial space in both the F2 and F1 layers. Note that this is the only axis that provides a direct connection between nuclei; the semi-transparent sphere in the F3 layer will have its own layer of 12 spheres, and therefore qualifies as a nucleus.

- The axis of the 6 great circles (bottom left) is unique in that it forms an unbroken chain of spheres in direct contact with one another. The semi-transparent sphere in the F1 shell is in direct contact with the nucleus.

- The axis of the 12 great circles (bottom right) connects the semi-transparent sphere in the F2 layer with the nucleus after having passed through what Fuller calls the “kissing point”, i.e., the point of contact between two spheres in the F1 layer.

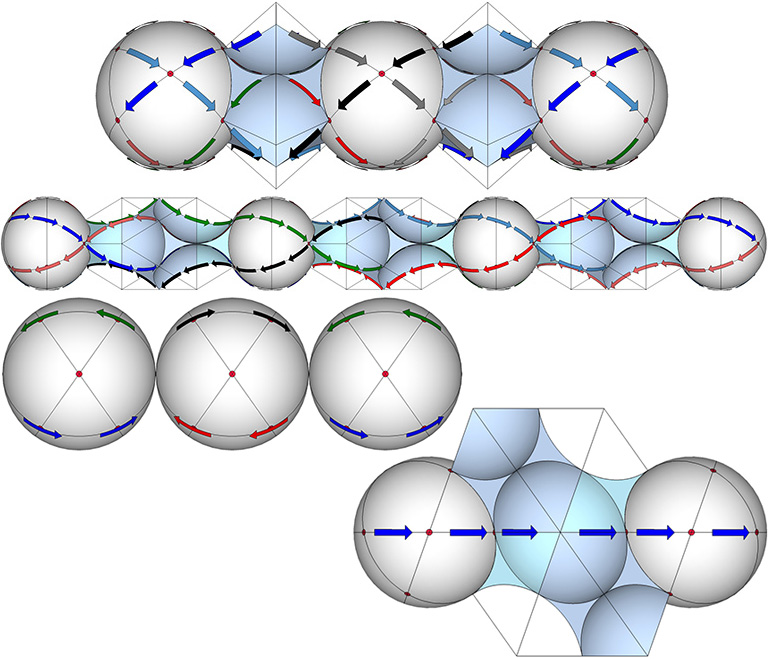

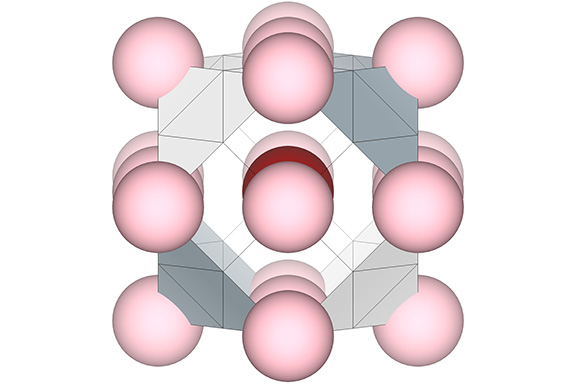

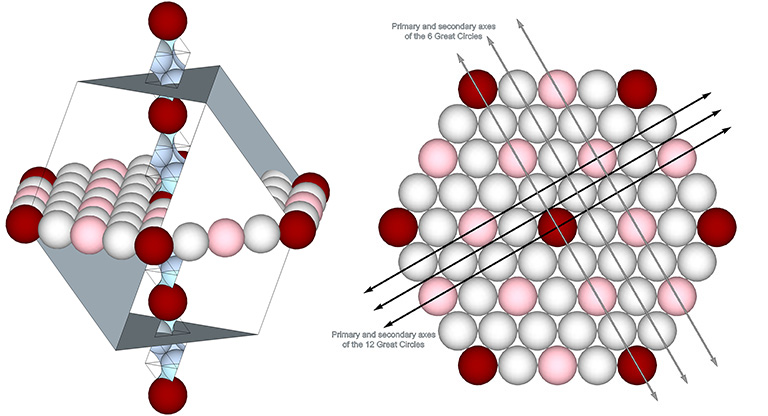

Set of 3 Great Circles of the VE

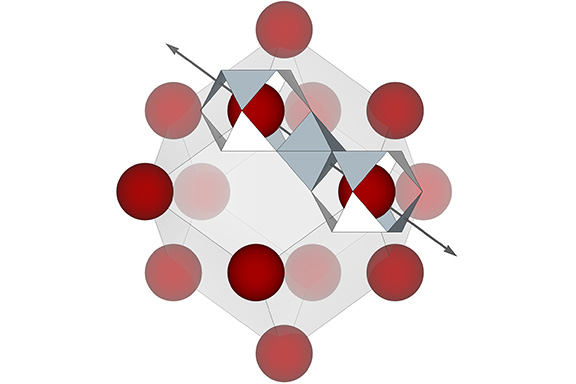

The axes of the 3 great circles pass through the centers of opposing square faces of the VE. Its primary axis connects nuclei in every fourth layer. Their great circle planes are in alignment with the three unique axes for the 3 Great Circles, and two of the three unique axes for the 6 Great Circles.

The axes pass alternately through a space (concave VE) and a sphere (convex VE). On the primary axes, the spheres alternate between nuclei (shown in red) and nuclear voids (pink). On the two secondary axes (those that do not pass through a nuclear sphere), the spheres are either all nuclear voids (pink) or spheres that occupy the F1 shells of nuclei. Shell spheres are shown in white. (See: Categories of Spheres in the Isotropic Vector Matrix: Nuclei, F1 Shells, and “Nuclear Voids”.)

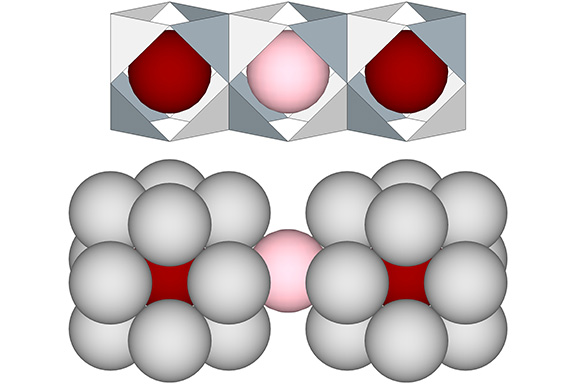

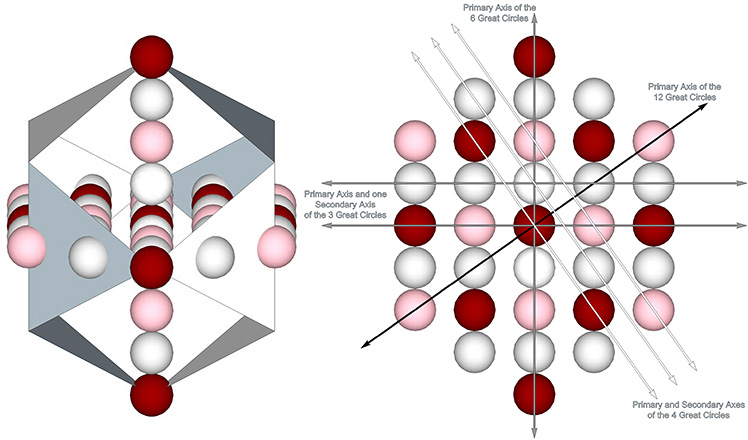

Set of 4 Great Circles of the VE

The axes of the 4 great circles pass through the centers of opposing triangular faces of the VE. Its primary axis connects nuclei in every 3rd layer. Their great circle planes are in alignment with the three unique axes for the sets 6 and 12 Great Circles.

The primary axis joins nuclei. The secondary axes join nuclear voids or shell spheres. Between each sphere on the axes is interstitial space consisting of a space (concave VE) flanked by one positive and one negative interstice (concave octahedra). See: Spheres and Spaces, and; Spaces and Spheres (Redux).

The axis of the set of four great circles is unique in that no single geodesic path directly joins the spheres along the axis. See Inter-Sphere Connections via the 25 Great Circles of the VE.

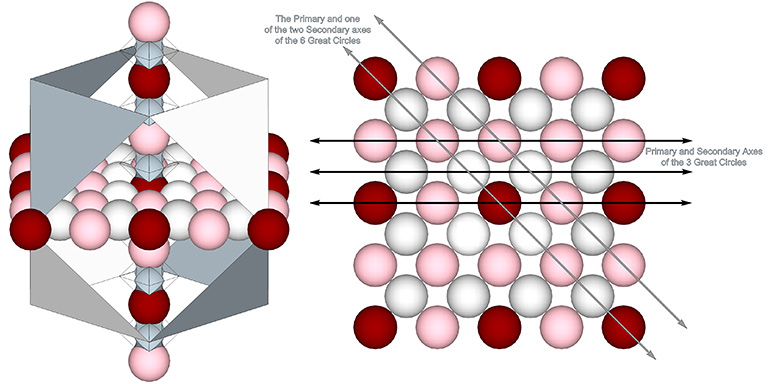

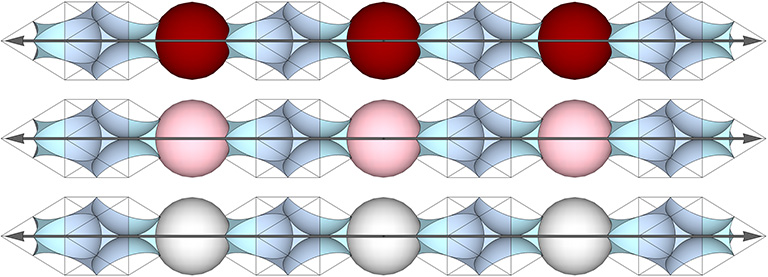

Set of 6 Great Circles of the VE

The axes of the 6 Great Circles pass through opposing vertices of the VE. Its primary axis connects nuclei in every fourth layer. Their great circle planes are in alignment with the three unique axes of the 4 Great Circles, the primary axis and and one secondary axis of the 3 great circles, and the primary axis of the 6 and 12 Great Circles.

The primary axis joins nuclei and nuclear voids between each of which is a shell sphere. One secondary axes joins nuclear voids each separated by a shell sphere, and the other secondary axis forms an unbroken chain of shell spheres.

Set of 12 Great Circles of the VE

The axes of the 12 Great Circles pass through the centers of opposing edges of the VE. Its primary axis connects nuclei in every fifth layer. Their great-circle planes are in alignment with the three unique axes of the 4 Great Circles, and the primary axis of the 6 Great Circles.

Primary and secondary axes of the 12 great circles follow the same pattern as the axes of the 6 great circles, but with all all spheres separated by interstitial space.

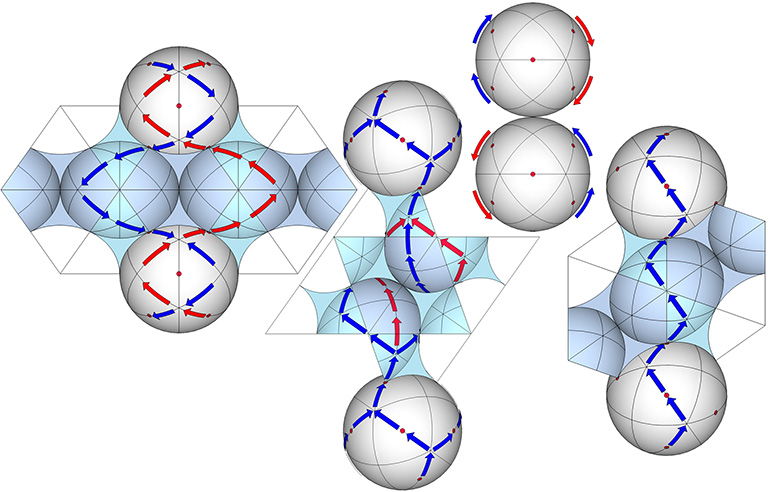

Knowing how the three categories of spheres are distributed along the primary axes should enable us to count the total number of nuclei in each shell of the vector equilibrium. The primary axes for the sets of 3 and 6 Great Circles pass through a nucleus with every fourth shell. The primary axis for the Set of 4 Great Circles passes through a nucleus with every third shell And, the primary axes of the set of 12 Great Circles pass through a nucleus with every eighth shell. It follows that only those shells which are multiples of 3, 4 and 8 contain nuclei. The F1, F2, and F5 shells, for example, have none. We also know that nuclei are evenly distributed on a grid of rhombic dodecahedra (see Formation and Distribution of Nuclei in Radial Close-Packing of Spheres), and that the shell growth formula for the rhombic dodecahedron is 12F²+2 (see Concentric Sphere Shell Growth Rates). If anyone knows, or is able to derive the formula, please share.