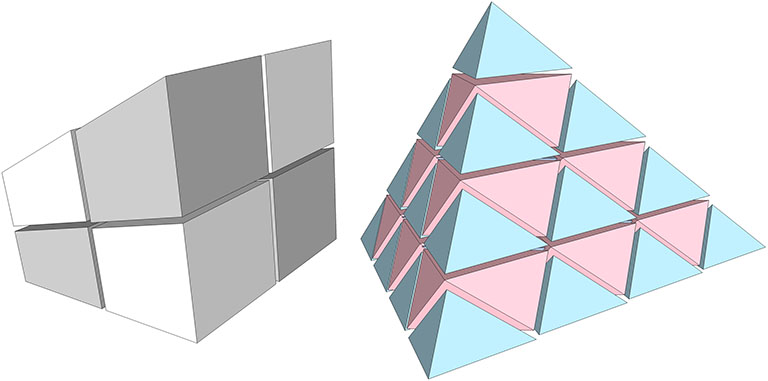

While irregular cubes subdivide into dissimilar six-sided polyhedra, any tetrahedron, regular or irregular, will always subdivide into similar tetrahedra and octahedra.

The perimeter of any rectangle defined by the section plane of a regular tetrahedron cutting perpendicularly through its edge-to-edge axis is a constant equal to 2 times its edge length.

Any tetrahedron, regular or irregular, may be sliced parallel to any one or more of its faces without losing its basic symmetry. Or, as Fuller observed, “only the tetrahedron’s four-dimensional coordination can accommodate asymmetric aberrations without in any way disrupting the symmetrical integrity of the system.” (Synergetics, 100.304)

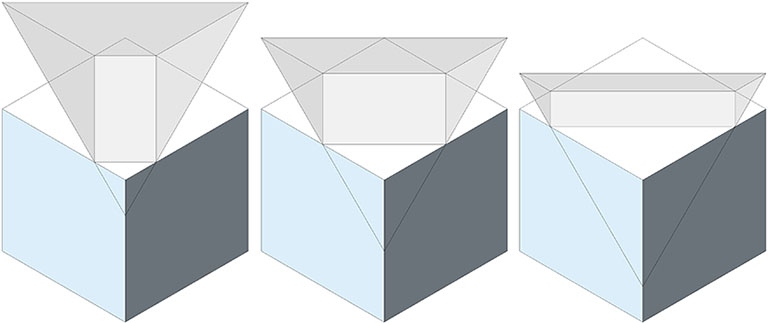

The pulling outward or pushing inward of one or more faces of the tetrahedron accomplishes the same transformation as uniform scaling would achieve. This accommodation of asymmetrical aberrations while preserving its symmetrical integrity allows for the linear translation of the its center of gravity without actually moving the tetrahedron.

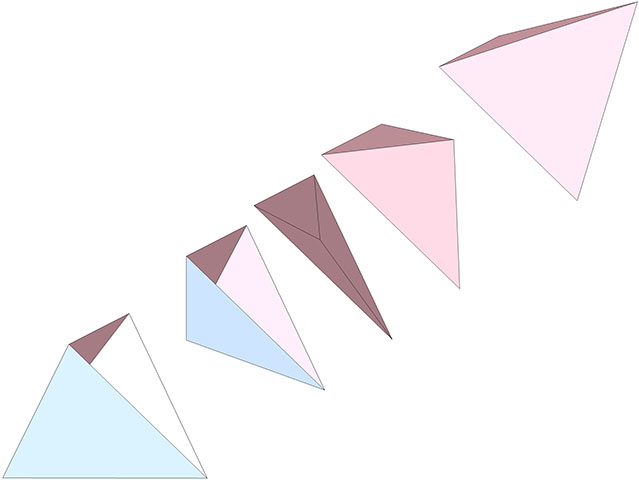

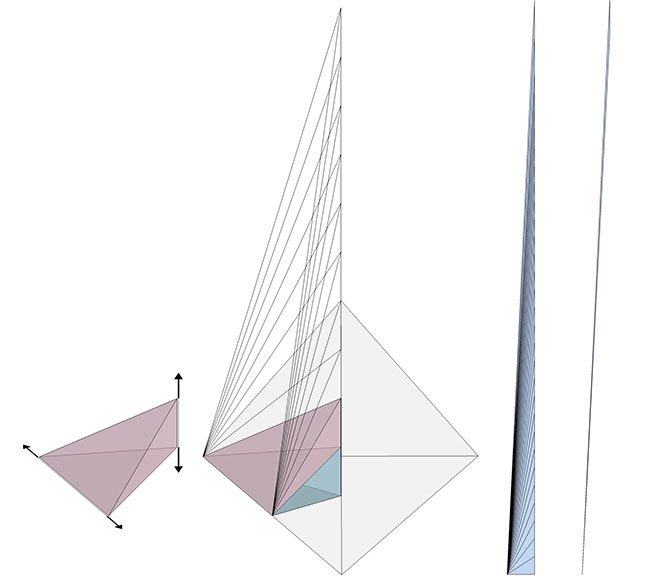

The illustration below shows the same transformation, but with the two actions performed simultaneously, i.e., the pulling outward of one face occurs at the same time and at the same rate as the other face is pushed inward. This is essentially equivalent to a linear translation of the tetrahedron. We can accomplish any translation to any coordinates using this method, something that is possible with no other polyhedron.

The tetrahedron may be turned inside out by pushing a vertex through the opening of its opposite face.

Each consecutive (non-oscillating) inside-outing produces a unique orientation of the tetrahedron, and results in an infinite or near-infinite number of helices or helical translations. See also: Tetrahelix.

The tetrahedron may also turn itself inside-out by rotating three of its triangular faces outward from their common vertex like the petals of a flower. The process may be halted before the vertices rejoin on the opposite side, with the result being an octahedron rather than another tetrahedron. In the octet truss network, the octahedra occupy the spaces between tetrahedra. In the isostropic vector matrix, the octahedron defines the space between the spheres which in turn are defined by positive and negative tetrahedra sharing a common vertex at the center of the vector equilibrium (VE). It seems appropriate, therefore, to conceive of the octahedron as a positive and a negative tetrahedron turned inside-out, as the illustration below demonstrates.

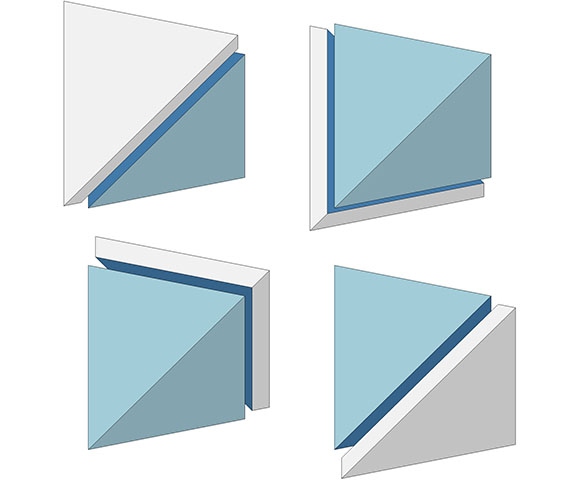

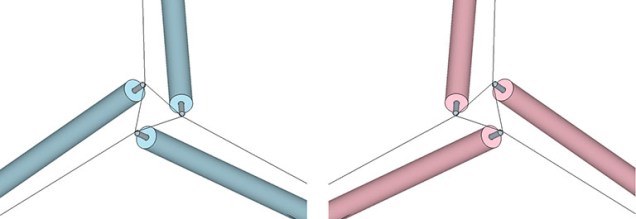

The tetrahedron is uniquely ambidextrous. By this, I mean that we can model the transformation from the positive to the negative tetrahedron non-destructively, i.e., without violating any of the principles that determine its structural or symmetrical integrity. To demonstrate, we need the tensegrity model.

As I’ve said elsewhere, anything in the universe (both physical and metaphysical as Fuller would insist on saying) that may be called structural is structured on tensegrity principles. The structural polyhedra (the tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron, and the geodesic polyhedra derived from them) can all be modeled as both polyhedral and spherical tensegrities. But only the tetrahedron may pass through its spherical phase and reverse polarity, with its vertices defined by either a clockwise or counter-clockwise tension loop. The remaining polyhedra are locked into a clockwise or counter-clockwise orientation, and cannot, non-destructively, reverse themselves. See also: Dual Nature of the Tetrahedron.

The transformation from a positive, or clockwise tetrahedron, to a negative, or counter-clockwise tetrahedron, is what spontaneously drives the jitterbugging of the isotropic vector matrix. See Jitterbug.

Fuller, taking his A and B quanta modules as inspiration, elaborated on their constancy of volume by continuing the progression out to infinity. Ultimately, we have something indistinguishable from a line, but with the volume of of the original tetrahedron. Fuller regarded this as a model of the photon. While we may imagine a photon traveling through space and time from its origin to its destination, the photon, from its own point of view, is already there.

A similar constancy is observed when we orient the tetrahedron on its edge-to-edge axes. The highly skewed half-octahedra in the illustration below each have the same volume as the original tetrahedron.