“The closest-packed symmetry of uniradius spheres is the mathematical limit case that inadvertently captures all the previously unidentifiable otherness of Universe whose inscrutability we call space. The closest-packed symmetry of uniradius spheres permits the symmetrically discrete differentiation into the individually isolated domains as sensorially comprehensible concave octahedra and concave vector equilibria, which exactly and complementingly intersperse eternally the convex “individualizable phase” of comprehensibility as closest-packed spheres and their exact, individually proportioned, concave-in-betweenness domains as both closest packed around a nuclear uniradius sphere or as closest packed around a nucleus-free prime volume domain.”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 1006.12

Spaces, like spheres, have surfaces. The interstitial model of the isotropic vector matrix (IVM) makes evident that it is the sphere’s surfaces (both its convex and its concave surfaces) that matter. Electric charge is carried on the surface of the conductor. Molecular biology is all about the lock and key system of protein surfaces and shapes. The surface of the “space” in the isotropic vector matrix is a continuity broken only be the seams at the interface of the concave “spaces” and “interstices” (see below). These seams align with the four great circles of the vector equilibrium (VE), and describe the most efficient paths between the points of contact with adjacent spheres. See also: Anatomy of a Sphere.

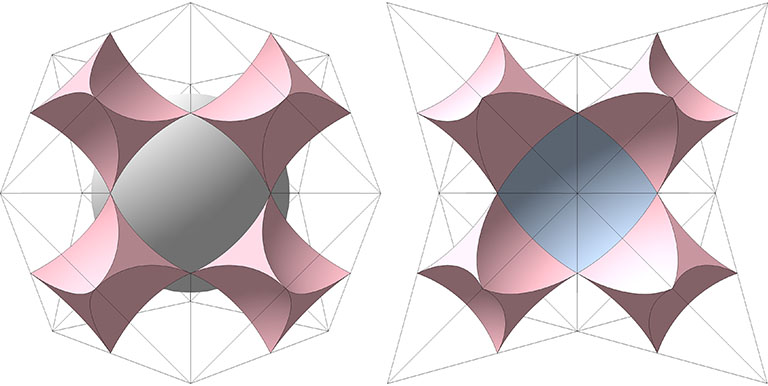

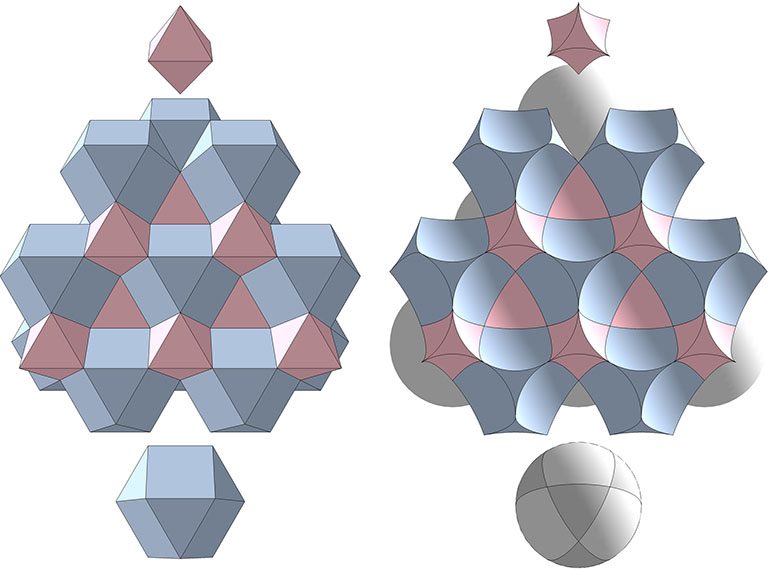

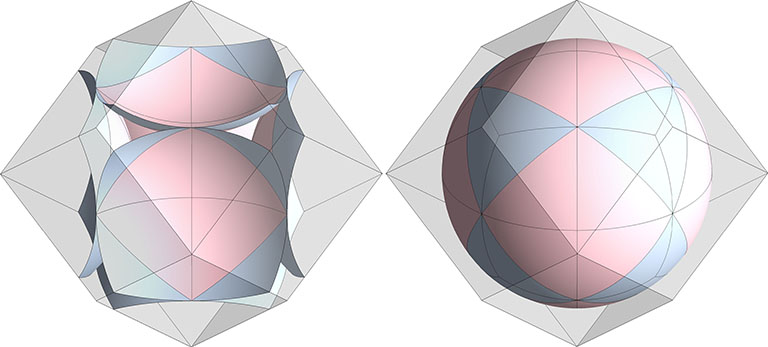

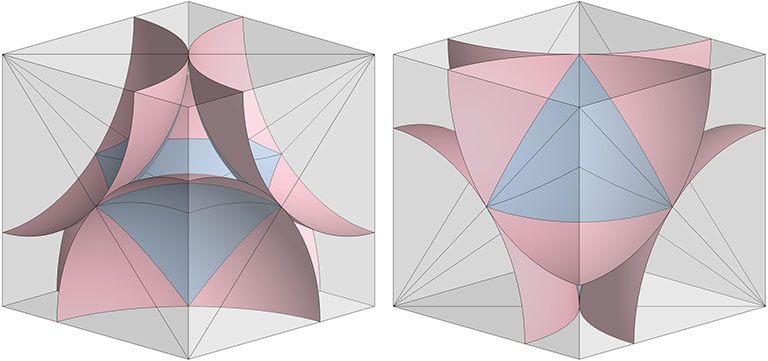

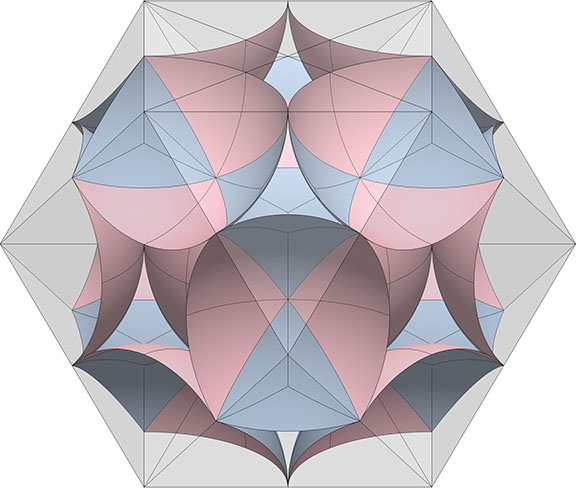

The figure below shows the exact correlation between two models of the isotropic vector matrix, a correspondence that Fuller attempted to describe in the excerpt I’ve quoted above.

Though the VEs (blue) and octahedra (pink) on the left align with the spaces (blue) and interstices (pink) on the right, close inspection of the above models reveals a key difference. The model on the left does not distinguish between spheres and spaces. While on the right the difference is obvious, on the left both spheres and spaces are represented by identical VEs. The ambiguity is apt: In the isotropic vector matrix, there is a one-to-one identity between the spheres and spaces; one is simply the other turned inside out.

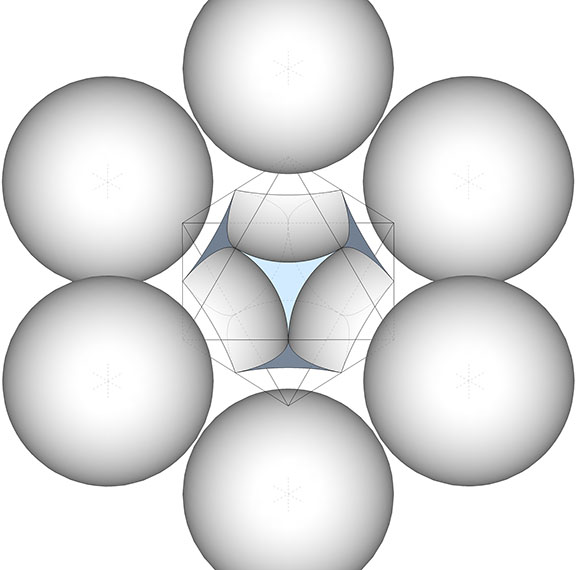

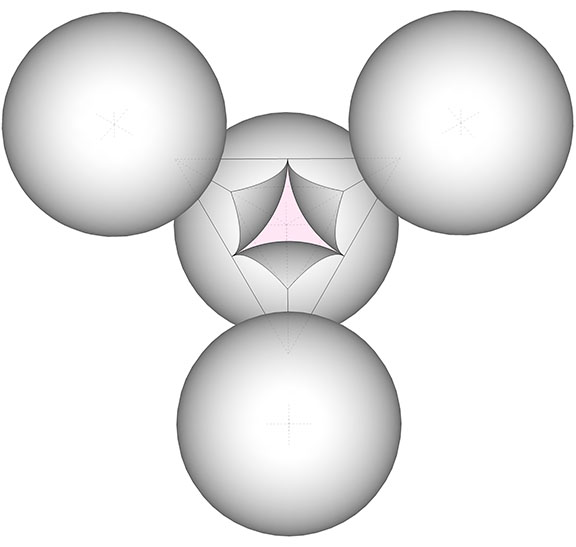

The model on the right is what I’m calling the interstitial model of the isotropic vector matrix. It consists of concave vector equilibrium (VE) spaces and concave octahedron interstices. The concave VE is the shape of the void at the center of six close-packed spheres defining the octahedron. The concave octahedron is the shape of the void at the center of four close-packed spheres defining the tetrahedron.

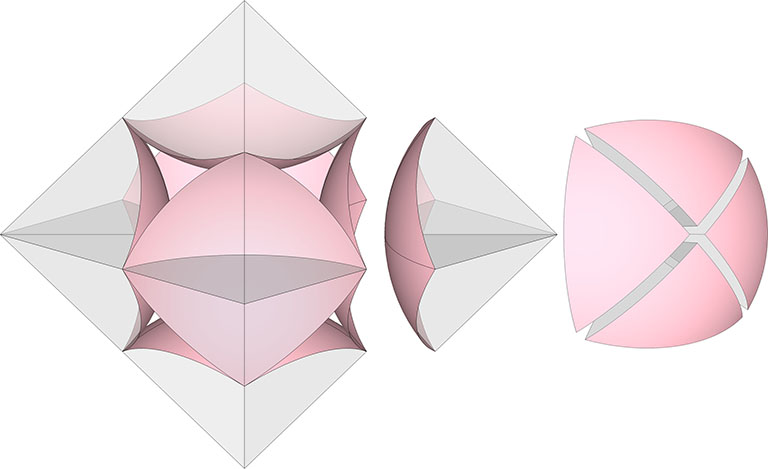

Concave VE (“space”)

Because it occupies the space in the isotropic vector matrix that is replaced by a sphere in the jitterbug transformation, I reserve the term “space” for the concave VE at the common center of the six close-packed spheres of the regular octahedron.

Concave Octahedron (“interstice”)

The void at the center of four close-packed spheres has the shape of a concave octahedron which I call the “interstice” to distinguish it from the “space” referred to above. The interstices maintain both their shape and position during the jitterbug transformation, while their 90° rotations articulate the sphere-to-space oscillations described below.

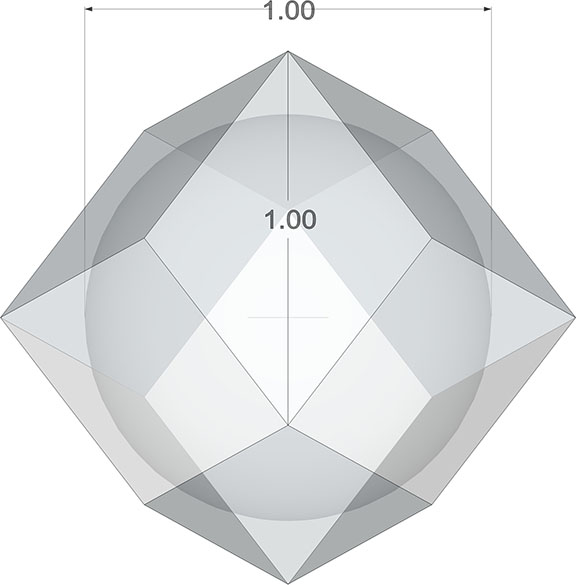

Spherical Domains

The polyhedra of the isotropic vector matrix divide the spheres into rational sections which, when added together, constitute the polyhedron’s spherical domain. Fuller thought this rationality was sufficient to eliminate pi (π) from his geometry. He’d already shown that the volumes of most polyhedra were rational if instead of the cube we used the regular tetrahedron as the unit volume. And if we replaced the irrational volume of the sphere with the rational sections carved from the rational polyhedra, pi was irrelevant.

| Rhombic Dodecahedron | 144 quanta modules | 1 spherical domain |

| Vector Equilibrium (VE) | 480 quanta modules | 3.40 spherical domains |

| Cube | 72 quanta modules | 1/2 spherical domain |

| Octahedron | 96 quanta modules | 3/5 spherical domain |

| Tetrahedron | 24 quanta modules | 1/5 spherical domain |

Octahedron

The six spheres at the vertices of the octahedron define the concave vector equilibrium space at its center. The planar facets of each vertex carve a 1/10 section from its sphere. The 1/10 section is further subdivided to form the four 1/40 sections used in the spherical domain calculations. The total spherical domain of the planar octahedron is 3/5.

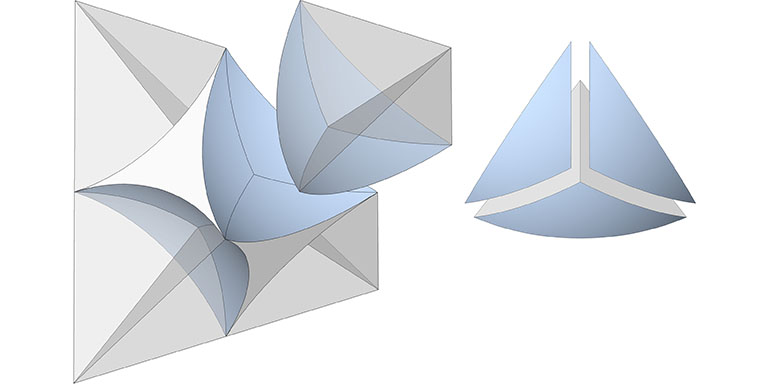

Tetrahedron

The four spheres at the vertices of the tetrahedron define the concave octahedron interstice at its center. The planar facets of each vertex carve a 1/20 section from its sphere. The 1/20 section is further divided to form the three 1/60 sections used in the spherical domain calculations. The total spherical domain of the planar tetrahedron is 1/5.

Rhombic Dodecahedron

There are two rhombic dodecahedra in the isotropic vector matrix—one with a space at its center, and one with a sphere. For the rhombic dodecahedron with a space at its center, each of the six acute vertices define the center of a sphere from which the planar facets of each carve a 1/6 section. Both of the planar rhombic dodecahedra contain precisely one spherical domain.

Note that one is made from the other by reversing the 1/6 sections so that their peaks point either inward to define the sphere, or outward to define the space.

Cube

There are two cubes in the isotropic vector matrix, one a 90° rotation of the other. Their rotation comprises the jitterbug transformation and the exchange between spheres and spaces. Four of its eight vertices each define the center of a sphere from which the planar facets of each carve a 1/8 section. The planar cube contains precisely 1/2 spherical domain.

Vector Equilibrium (VE)

The twelve vertices of the VE each define the center of a sphere from which the planar facets carve a 1/5 section. These plus the nuclear sphere add to a total of 3.4 spherical domains.

Ratio of Spheres to Spaces in the Isotropic Vector Matrix

While the sphere-to-space ratio differs for the polyhedra, when the isotropic vector matrix is considered as a whole the ratio approaches that of the rhombic dodecahedron; rhombic dodecahedra close pack exactly as spheres close pack, and the rhombic dodecahedron constitutes one spherical domain.

The volume of the unit-diameter sphere is π√2 tetrahedra and the volume of the rhombic dodecahedron which contains that sphere is six unit tetrahedra. So, the sphere-to-space ratio is (π√2)/(6 – π√2), or ≈ 2.853275. Fuller wanted this number to be rational. It is not.

Sphere-to-Space and Space-to-Sphere Oscillation of the Jitterbug

The interstitial model provides the most literal interpretation of the space-to-sphere oscillations of the jitterbug. The tetrahedron’s polarity reversal is accomplished by a 90° rotation of the concave octahedron interstices which alternately disclose the nuclear sphere, on the left in the illustration below, and the nuclear space, on the right: