Fuller’s four primary models of the isotropic vector matrix—as vectors, as spheres, as the interstices between spheres, and as A and B quanta modules, are as distinct as they are inseparable. Each serves different purposes in Fuller’s geometry, and the terms used for one model are not necessarily synonymous with the same terms applied to another.

For example, the regular tetrahedron and the regular octahedron of the vector model each complement the other to fill all-space. In the sphere model, the tetrahedron is comprised of four spheres that define the domains of the tetrahedron’s four vertices in the vector model, and likewise, the octahedron is comprised of six spheres defining the domains of its vertices. These tetrahedra and octahedra do individually close-pack in the sphere model.

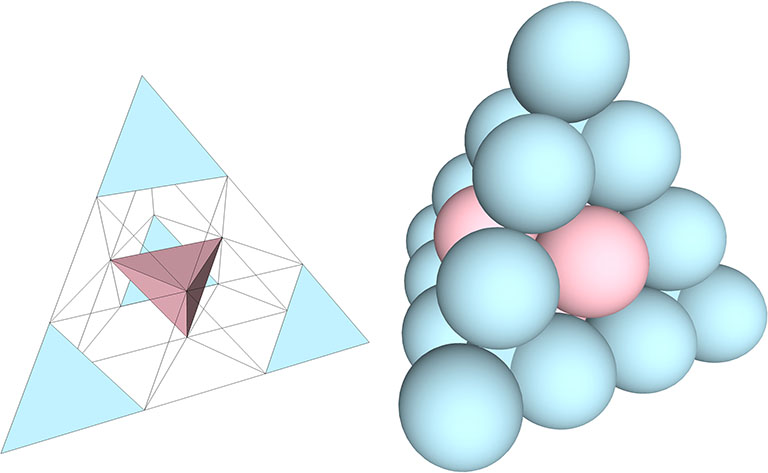

In the first illustration below, five 4-sphere tetrahedra (four positive and one negative) have been stacked to form the F3 tetrahedron on the right. On the left is the vector model of the same F3 tetrahedron. You’ll note that the domains of all the vertices are occupied by the four-sphere tetrahedra in the sphere model, even though space remains (in the shape of edge-bonded octahedra) between the tetrahedra in the vector model.

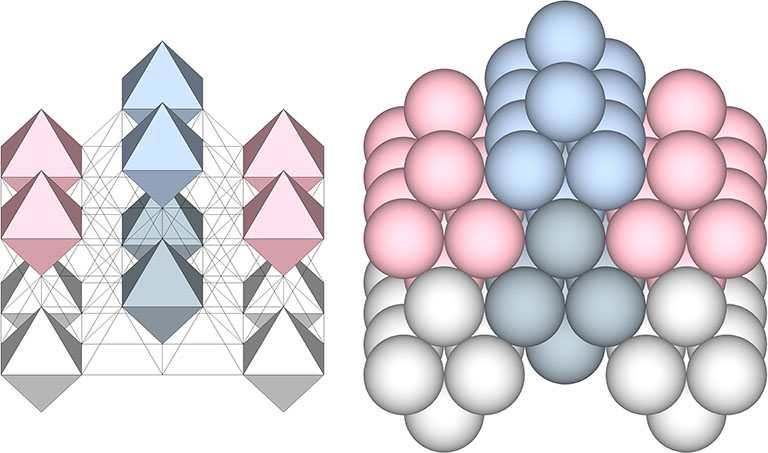

Similarly, six-sphere octahedra (right) close-pack to occupy the domains of all the vertices in the vector model (left):

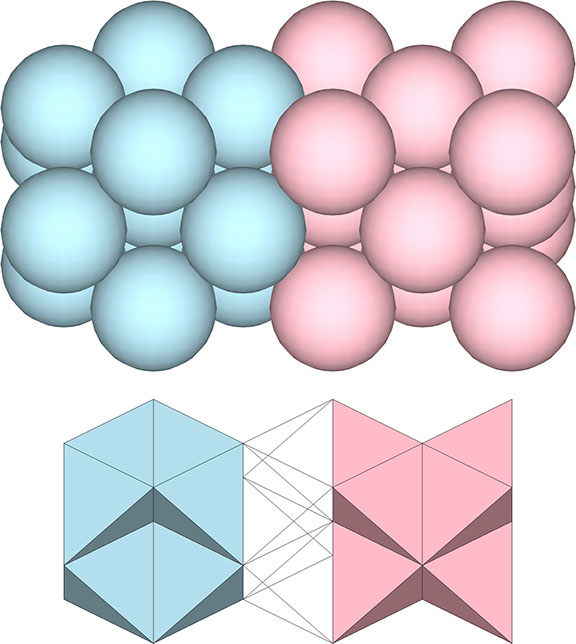

And, 13-sphere VEs and 14-sphere cubes (top) close-pack in combination to occupy the domains of every vertex in the vector model (bottom):

Incidentally, this last illustration is also a model of the jitterbug transformation. See: Jitterbug.

Another way of thinking about the different models of the isostropic vector matrix is to imagine the spheres model as squeezing the vector model’s close-packed tetrahedra and octahedra into the concave VEs and concave octahedra of the interstitial model. (See Spheres and Spaces, and Spaces and Spheres (Redux).)