Note: For instructions on how to construct the Weaire-Phelan structure, see my post: Construction Method for the Pyritohedron and Tetrakaidecahedron of the Weaire-Phelan Structure.

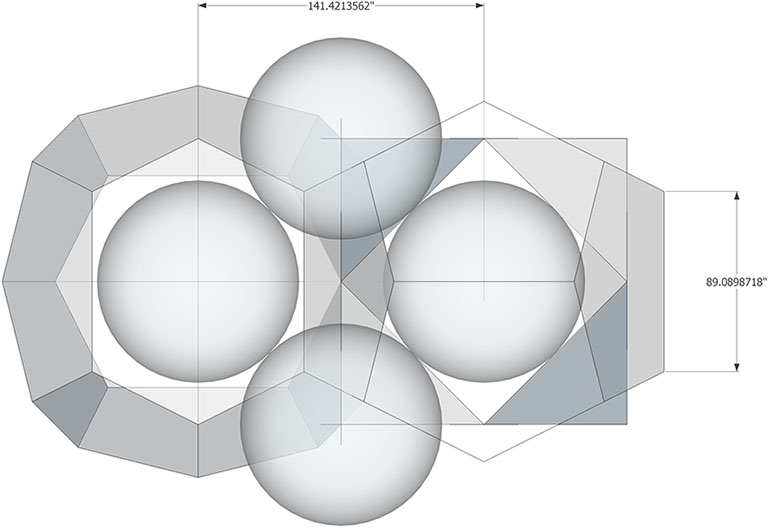

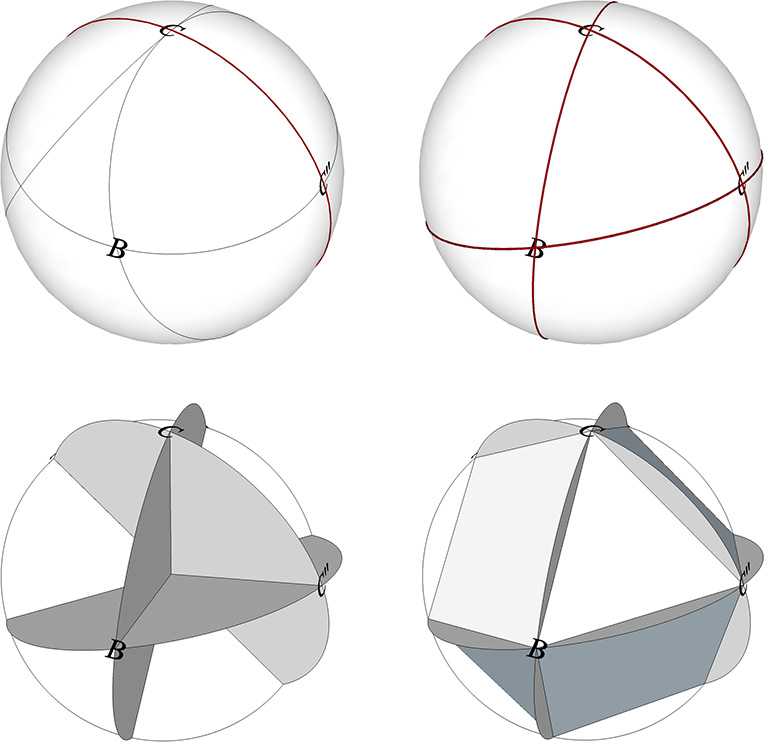

Pyritohedra and tetrakaidecahedra close pack to constitute the Weaire-Phelan structure (or Weaire-Phelan “matrix” as I prefer to call it, and, when dimensioned appropriately, align precisely with the distribution of nuclei in the isotropic vector matrix. The unit vector (d in the illustration below) is identical with the unit vector (sphere diameter) of the isotropic vector matrix.

The pyritohedron and, presumably, the tetrakaidecahedron have identical rational volumes in both cubic and tetrahedral units of measure. For the cubic volume, we take the long edge of the pentagonal face as the unit length (a in the illustrations). For the tetrahedral volume, we take the diameter of the sphere as the unit length (d in the illustrations).

When we measure the angles, edge lengths, and radii of the pyritohedron, the numbers do not inspire confidence. It would seem unlikely that so many irrational numbers could possibly result in a rational, whole-number volume. But they do.

a = long edge or base of pentagonal face

d = diameter of sphere*

d = a × ³√4 × √2/2

a = d × ³(√2/2) = (d√2)/(³√4) = d√2 × ³√(1/4)

*d is identical with the unit vector of the isotropic vector matrix. In the Weaire-Phelan matrix, it aligns with the height vectors connecting the base with the peak of the smaller of the two pentagonal faces of the tetrakaidecahedron, and to the radial vectors connecting the height vector’s endpoints (see illustration below).

The long edge of the pyritohedron’s pentagonal face, a, (which, when taken as unit length results in a cubic volume for the pyritohedron of 4a³) seems to be related to the diameter of the sphere, d, by ³(√2/2) or about 0.890898718. I don’t have a geometric proof to account for the appearance of this third root, but the number seems to work to at least 7 decimal places in my computer models, and the irrational roots cancel out perfectly in the volume calculations to produce the rational result of 24d³ for the tetrahedral volume.

Pyritohedron specifications:

- 12 irregular pentagonal faces, 20 vertices, 30 edges

- Face angles:

- atan(2√5) + atan(√5/4) ≈ 106.6015496°

- atan(√5/10)+90° ≈ 102.6043826°

- 2atan(4√5/5) ≈ 121.588136°

- Dihedral angle: 2atan(2) ≈ 126.8698976°

- Volume (in tetrahedra): 24a³√2

- Volume (in tetrahedra): 24d³

- Cubic volume: 4a³

- Cubic volume: 2d³√2

- Quanta modules: 576 modules, types unknown*

- Surface area (in equilateral triangles): 8a²√15

- Surface area (in squares): 6a²√5

- In-sphere radius: 2a/√5

- Mid-sphere radius (center to mid-long-edge): a

- Circum-sphere radius: a√5/2

*It should be possible to construct the pyritohedron from quanta modules, but may involve one or more variants of those quanta modules already described by by Fuller.

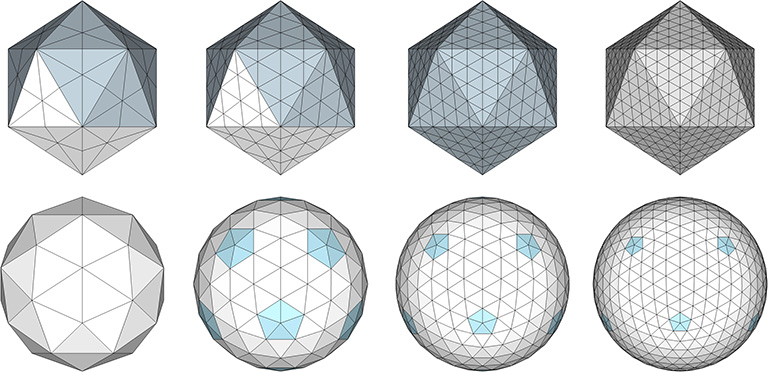

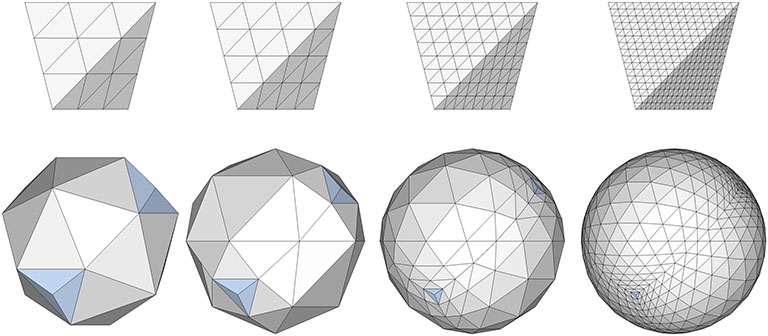

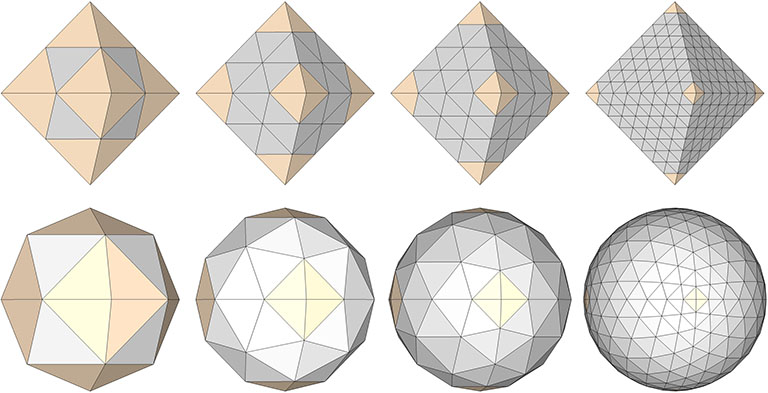

The image below shows my computer model with the calculated dimensions accurate to 7 decimal places.