“When four tetrahedra of a given size are symmetrically intercombined by single bonding, each tetrahedron will have one of its four vertexes uncombined, and three combined with the six mutually combined vertexes symmetrically embracing to define an octahedron; while the four noncombined vertexes of the tetrahedra will define a tetrahedron twice the edge length of the four tetrahedra of given size; wherefore the resulting central space of the double-size tetrahedron is an octahedron. Together, these polyhedra comprise a common octahedron-tetrahedron system.”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 422.03

Nature’s simplest structural system is the tetrahedron. Regular tetrahedra, however, do not combine to fill all-space (as do cubes, for example). In order to fill all-space, the regular tetrahedron must be complemented by the regular octahedron. Together they produce what Fuller conceived as the simplest, most powerful structural system in the universe, the octahedron-tetrahedron system, which he was able to patent in 1961 and subsequently copyright under the trademark name, the “octet truss.”

If we stack six octahedra edge-to-edge to create a larger octahedron we discover that we have inadvertently produced eight tetrahedra at its center. The eight edge-bonded tetrahedra share a common vertex and form the vector equilibrium (VE).

Another name for this system of all-space-filling tetrahedra and octahedra is the isotropic vector matrix.

One of the simplest ways to construct the octahedron is to orient three squares to the three planes of the Cartesian grid, centered on the origin and turned so that each of their vertices lie on the axes.

The Regular Octahedron

a = edge length

- 8 equilateral triangle faces, 6 vertices, 12 edges

- Face angles all 60°

- Dihedral angle: acos(-1/3) ≈ 109.4712°

- Central angles: all 90°

- Volume (in tetrahedra): 4a³

- Cubic volume: a³×√2/3

- A quanta modules: 48

- B quanta modules: 48

- Total quanta modules: 96

- Surface area (in equilateral triangles): 6a²

- Surface area (in squares): 6√3a²/4

- In-sphere radius: a√6/6

- Mid-sphere radius: a/2

- Circum-sphere radius: a√2/2

The surface, central, dihedral, and other interior and exterior angles of the regular octahedron.

The in-sphere (center to mid-face), mid-sphere (center to mid-edge), and circumsphere (center to vertex) radii of the octahedron.

The regular octahedron consists of 96 quanta modules, evenly distributed between A and B modules with 48 each.

The regular octahedron can be constructed from a single paper strip along seven consecutive folds of atan(2√2), or approximately 70.5288°, each. See also: Polyhedra From Polygonal Strips.

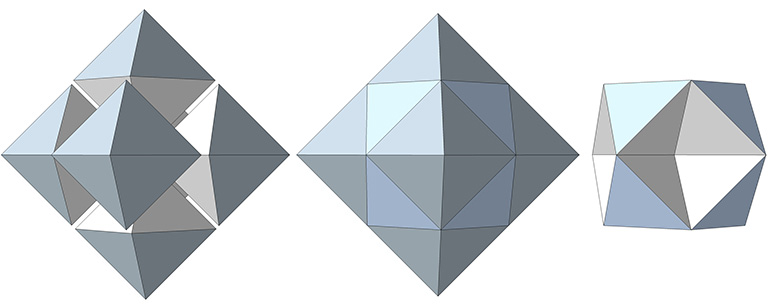

The octahedron may be produced through the unfolding of one positive and one negative tetrahedron.

The octahedron can also be produced from one positive or one negative tetrahedron alone. This produces an octahedron of four triangular facets and four empty triangular windows. This can be demonstrated through a kind of jitterbug transformation, as shown in the figure below.

Spheres close-pack as octahedra around a central sphere or nucleus in even numbered layers only. The odd numbered layers surround a space, or concave vector equilibrium (VE).

Number of spheres in outer shell: 4F²+2

F = edge frequency, i.e., the number of subdivisions per edge

Total number of spheres: (4N³+2N)/6

N = number of spheres per edge

The tensor equilibrium phase of the octahedron suggests the overall shape of the VE, with its six vertex loops forming the square “faces” of the VE. As with all polyhedra, with the exception of the tetrahedron (see: The Dual Nature of the Tetrahedron), the vertex loops are oriented in either a clockwise or a counter-clockwise direction, and when pulled in tight form the six vertices of either the positive or the negative octahedron. (See also: Tensegrity.)

In the interstitial model of the isotropic vector matrix, the spaces between spheres occupy the positions defined by the octahedra in the vector model, and by one of the two rhombic dodecahedra in the quanta model. The spaces, i.e., the space between spheres close-packed as octahedra, describe a concave VE.

In the jitterbug transformation, the concave vector equilibria (VE’s) and their enclosing octahedra transform into spheres, and vice-versa. See: Spheres and Spaces; Spaces and Spheres (Redux), and; The Jitterbug.

All the structural (i.e. triangulated) polyhedra may be constructed from an even number triangular helices, or what Fuller called one half of a structural quantum. The tetrahedron and icosahedron require an equal number of clockwise and counter-clockwise helices. However, the octahedron is curiously constructed from an even number of clockwise, or an even number of counter-clockwise triangular helices, which seems to contradict our intuitive concept of structure as a knot of positive and negative forces.

This underscores, I think, our understanding of the octahedron as the space between the spheres, and the void between the tetrahedra, of the isotropic vector matrix.

Note further that the endpoints of the helices converge on just two of the octahedron’s six vertices, resulting in a preferred axis of spin, and of wave propagation (see Isotropic Vector Matrix as Transverse Waves.)