“… we observe the child taking the “me” ball and running around in space. There is nothing else of which to be aware; ergo, he is as yet unborn. Suddenly one “otherness” ball appears. Life begins. The two balls are mass-interattracted; they roll around on each other. A third ball appears and is mass-attracted; it rolls into the valley of the first two to form a triangle in which the three balls may involute-evolute. A fourth ball appears and is also mass-attracted; it rolls into the “nest” of the triangular group. . . and this stops all motion as the four balls become a self-stabilized system: the tetrahedron.“

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 100.331

“The mathematics involved in synergetics consists of topology combined with vectorial geometry. Synergetics derives from experientially invoked mathematics. Experientially invoked mathematics shows how we may measure and coordinate omnirationally, energetically, arithmetically, geometrically, chemically, volumetrically, crystallographically, vectorially, topologically, and energy-quantum-wise in terms of the tetrahedron.”

—ibid., 201.01

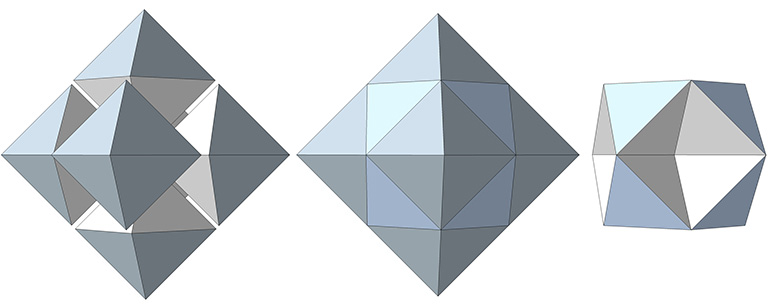

Nature’s simplest structural system is the tetrahedron. Regular tetrahedra, however, do not combine to fill all-space (as do cubes, for example). In order to fill all-space, the regular tetrahedron must be complemented by the regular octahedron. Together they produce what Fuller conceived as the simplest, most powerful structural matrix in the universe, the octahedron-tetrahedron matrix, which he was able to patent in 1961 and subsequently copyright under the trademark name, the “octet truss.”

This complementary relationship between the tetrahedron and its space-filling counterpart, the octahedron, is demonstrated by stacking four tetrahedra vertex-to-vertex to create a larger tetrahedron. In doing so, we discover that we have inadvertently produced an octahedron at its center.

Fuller considered this system of all-space-filling tetrahedra and octahedra to be nature’s own coordinate system: the isotropic vector matrix.

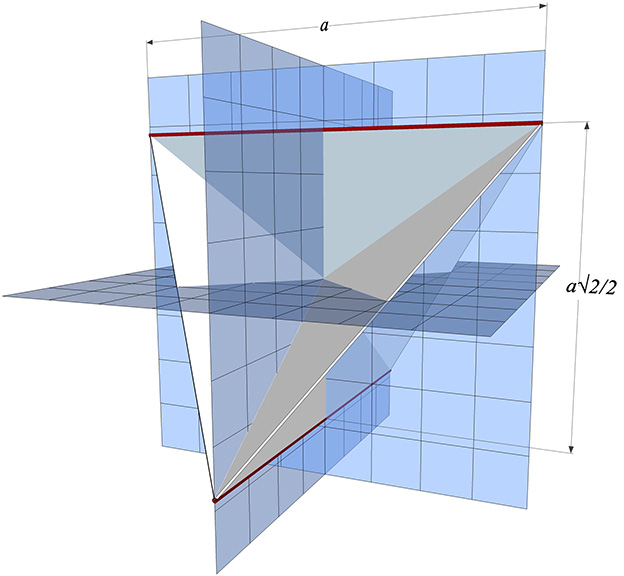

The regular tetrahedron is perhaps most easily conceived on the orthogonal grid as two unit length edges separated by a distance of √2/2 and oriented at 90° to the other (thick red lines in the figure below). Connecting their endpoints forms the the regular tetrahedron of edge length, a.

The Regular Tetrahedron

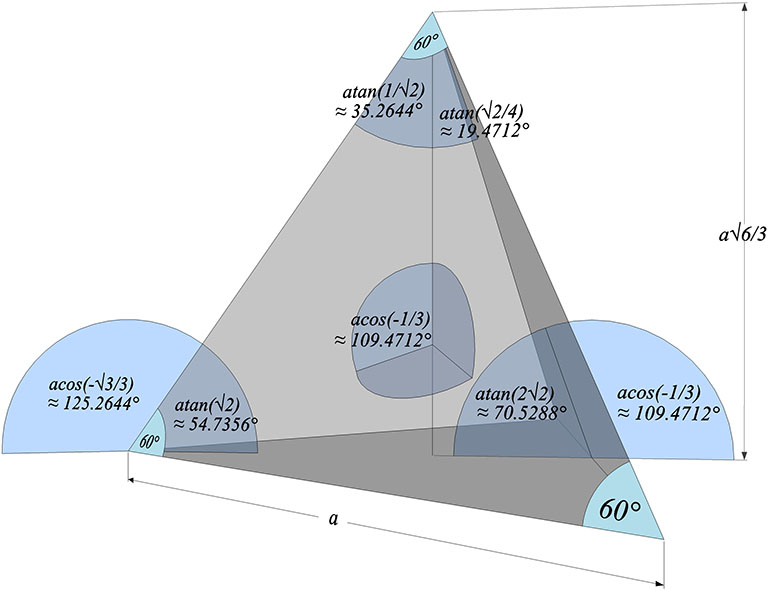

a = edge length

- 4 equilateral triangle faces, 4 vertices, 6 edges

- Face angles all 60°

- Central angles all arccos(-1/3) ≈ 109.4712°

- Dihedral angle: atan(2√2) ≈ 70.5288°

- Volume (in tetrahedra): a³

- Cubic Volume: a³√2/12

- A Quanta Modules: 24

- B Quanta Modules: 0

- Surface area (in equilateral triangles): 4a²

- Surface area (in squares) 4a²√3/4

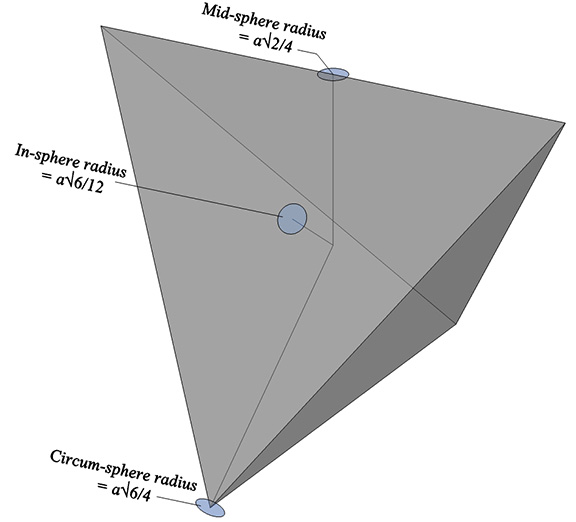

- In-sphere radius (center to mid-face): a√6/12

- Mid-sphere radius (center to mid-edge): a√2/4

- Circumsphere radius (center to vertex): a√6/4

The surface, central, dihedral and other angles of the regular tetrahedron:

The in-sphere radius (center to mid-face), mid-sphere radius (center to mid-edge), and circumsphere radius (center to vertex) of the regular tetrahedron:

The regular tetrahedron has three natural poles, or axes, of spin, the three axes running between mid-edges.

The A quanta module is derived from the regular tetrahedron. Through symmetrical quartering and bisecting the regular tetrahedron is divided into 24 A quanta modules, 12 positive and 12 negative.

The regular tetrahedron can be constructed from a paper strip with three consecutive folds of arccos(-1/3), approximately 109.4712°.

Spheres close pack as tetrahedra in even-numbered layers around octahedra (spaces) and VEs (spheres). In odd-numbered layers, the spheres surround a positive or negative tetrahedron (concave octahedron interstice). The growth pattern repeats every fourth layer, with the first layer surrounding a positive tetrahedron (concave octahedron interstice); the second layer surrounding an octahedron (concave VE space); the third layer surrounding a negative tetrahedron (concave octahedron interstice); and the fourth layer surrounding a VE (sphere).

Number of spheres in outer layer: 2F²+2

F = edge frequency, i.e., number of subdivisions per edge

Total number of spheres: [(N+1)³-(N+1)]/6

N = number of spheres per edge

A single sphere is free to rotate in any direction. Two tangent spheres are free to rotate in any direction but must do so cooperatively. Three spheres can rotate cooperatively about a single axis, i.e., they may involute and evolute along an axis perpendicular to the line connecting them with the center of the group. The addition of a fourth sphere acts as a lock, preventing all from rotating independently of the others. No rotation is possible, making the minimum stable closest-packed-sphere system: the tetrahedron.

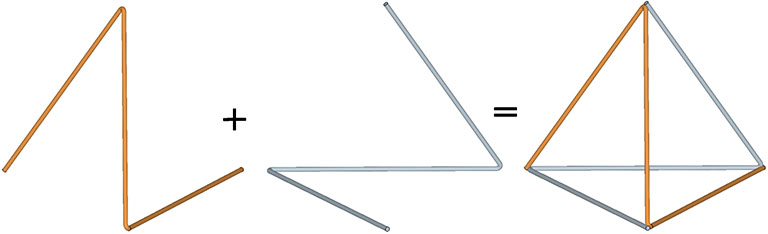

Two triangular helical units combine to form one 4-sided tetrahedron. 1+1 = 4. Fuller would use this as a primary example of synergy and complementation. The two additional triangles were always there but invisible until the first two were combined into a system.

The tetrahedron in its tensor-equilibrium phase has the overall shape of the Jessen orthogonal icosahedron. This 6-strut tensegrity is uniquely ambidextrous, i.e., neither right- nor left-handed; the vertex loops may be pulled inward to generate either a positive or a negative tetrahedron.

In the interstitial model of the isotropic vector matrix, the interstices occupy the positions defined by tetrahedra in the vector model, and by cubes in the quanta model. The interstices, i.e. the space between spheres close-packed as tetrahedra, describe a concave octahedron. (See Spheres and Spaces.)

This concave octahedron and its enclosing tetrahedron retain their shape and position throughout the jitterbug transformation. Only their orientation changes, with the tetrahedron rotating 90° between phases. See: The Jitterbug.

In any omni-triangulated structural system, that is, for any polyhedron structurally stabilized through triangulation:

- the number of vertices (“crossings” or “points”) is always evenly divisible by two;

- the number of faces (“areas” or “openings”) is always evenly divisible by four, and;

- the number of edges (“lines,” “vectors,” or “trajectories”) is always evenly divisible by six.

This holds true for any polyhedron of whatever its size or complexity, just so long as its faces (areas, openings) are all triangulated and therefore constitute a “structure” by Fuller’s definition, i.e. any system that holds its shape without external support. The point here is that the same numbers, two, four, and six, fundamentally describe the tetrahedron:

- The number of (non-polar) vertices in a tetrahedron is two;

- The number of faces (“areas” or “openings”) in a tetrahedron is four, and;

- The number of edges (“lines”, “vectors”, or “trajectories”) in a tetrahedron is six.

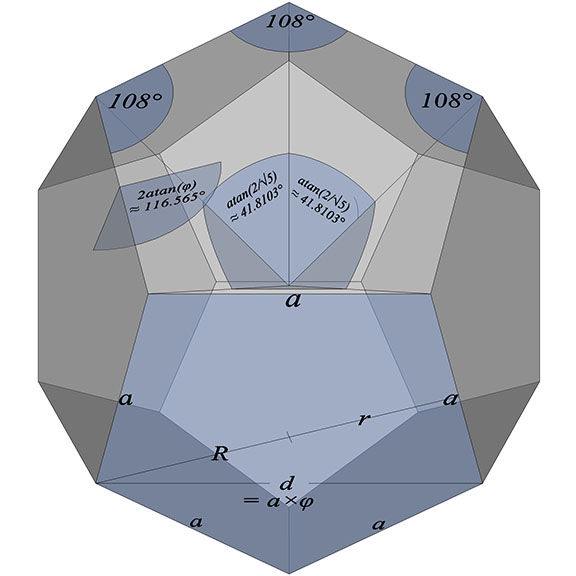

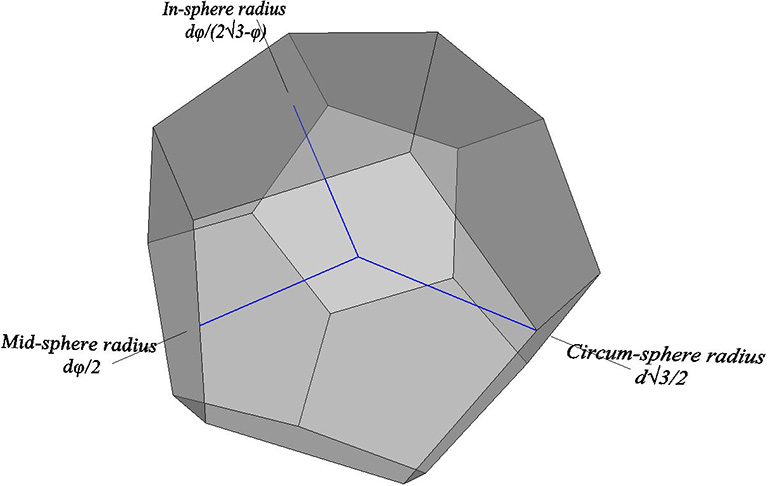

The tetrahedron is the minimum structural system and therefore the prime unit of volumetric measurement in Fuller’s geometry. The regular tetrahedron, unit-diagonal cube, octahedron, vector equiilbrium (VE), rhombic dodecahedron, and other polyhedra, both regular and irregular, all have rational, whole number volumes when measured in tetrahedra. See also: Polyhedra With Whole Number Volumes; Areas and Volumes in Triangles and Tetrahedra, and Calculating Volumes of Regular Polyhedra.