“Relationships Between First and Third Powers of F Correlated to Closest-Packed Triangular Number Progression and Closest-Packed Tetrahedral Number Progression, Modified Both Additively and Multiplicatively in Whole Rhythmically Occurring Increments of Zero, One, Two, Three, Four, Five, Six, Ten, and Twelve, All as Related to the Arithmetical and Geometrical Progressions, Respectively, of Triangularly and Tetrahedrally Closest-Packed Sphere Numbers and Their Successive Respective Volumetric Domains, All Correlated with the Respective Sphere Numbers and Overall Volumetric Domains of Progressively Embracing Concentric Shells of Vector Equilibria: Short Title: Concentric Sphere Shell Growth Rates.”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 971.01

The formulas for the close packing of spheres into clusters of triangles and tetrahedra follow the same sequential pattern as the number of unique pairings possible given a fixed number of objects. If N is the number of objects, the number of unique pairings is given by the formula, (N²-N)/2. The formula is the integral of the series (N-1)+(N-2)+(N-3)+…+(N-N), which represented graphically forms a triangle, with each element in the series forming a row of one less than the row below it. The formula for the total number of spheres comprising a triangle with n spheres along any one edge is (n²+n)/2. Because N in the previous formula equals n+1, we can rewrite the former as [(n+1)² – (n+1)]/2, and we can rewrite the latter as [(N-1)²-(N-1)]/2. In any case, if we stacked the results, they would form a tetrahedron. The formula for the total number of spheres comprising a tetrahedron with n spheres along any edge is [(n+1)³ + (n+1)]/6. This follows the pattern of the formula for the triangle, but the addition of ‘1’ follows the pattern of the formula for unique pairings.

Math sometimes hides rather than highlights patterns that would otherwise be obvious if we began with the geometric model. Spheres close pack as triangles and tetrahedra of frequency F, with F being the number of subdivisions of the edge vector. If we replaced n with F in the formulas for the close packing of spheres into triangles and tetrahedra, the formulas would be:

(F+2)²-(F+2)/2 = total spheres in triangle of frequency F

(F+2)³-(F+2)/6 = total spheres in tetrahedron of frequency F.

Both follow the pattern of the formula for pairings, and the ‘+2’ is likely the same ‘+2’ we find in the sphere shell growth rate formulas:

2F²+2 = sphere shell growth rate tetrahedron;

4F²+2 = sphere shell growth rate of octahedron;

6F²+2 = sphere shell growth rate of cube;*

10F²+2 = sphere shell growth rate of VE;

12F²+2 = sphere shell growth rate of rhombic dodecahedron*.

*The shells of the cube and the rhombic dodecahedron are not close-packed.

Fuller attributes this “additive two” to the pole of spin, a property essential to the definition of any system. But when talking about an individual sphere, he attributes the “+2” to the sphere’s two surfaces—the convex exterior and the concave interior (see Anatomy of a Sphere). When F=0, the vector equilibrium (VE) consists of a single sphere, the nucleus. But the shell growth rate formula returns 10(0)²+2 = ‘2’. Fuller, however, does not discard this as a mathematical absurdity. The universe is finite, though unbounded, and the sphere, like all polyhedra, has both a concave inside, which contains a definite part of the finite universe, as well as convex outside, that contains an indefinite part of the finite universe. See The Multiplicative and Additive Two.

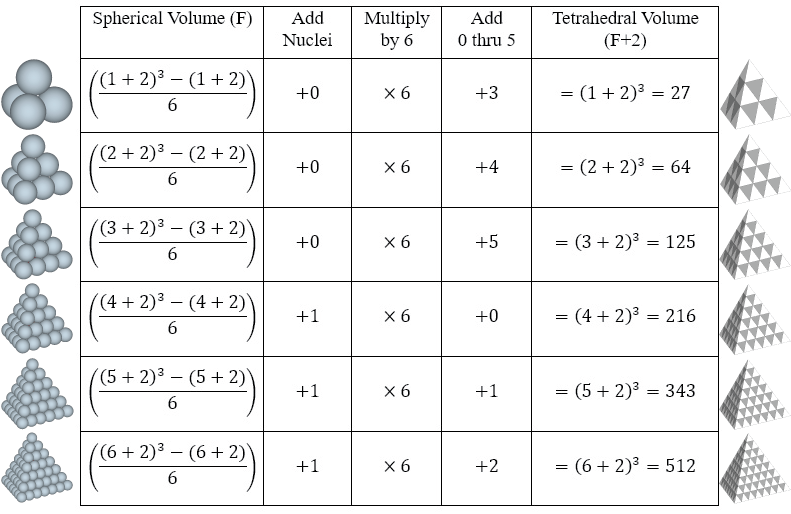

Fuller noticed a correlation between the tetrahedron’s spherical and tetrahedral volumes. By mathematically isolating the third power element in the formula for spheres, we observe a pattern that repeats in increments of 6, as disclosed in the following table:

Note further that the third-power element isolated from the spherical volume describes a tetrahedron with the same number of spaces as the number of spheres described by the original formula. For example, the spherical volume of the F1 tetrahedra in the left column of the above table is 4, and the number of spaces (i.e. octahedra) in the F2 tetrahedra in the right column is also 4. Remember that spheres and spaces exchange places in the oscillations of the isotropic vector matrix. (See also: Jitterbug, and Spheres and Spaces.)

I’m not convinced, however, that the first additive modifier (the second column of the table) is attributable to the number of nuclei. New nuclei emerge with every fourth layer, not every sixth, so Fuller may have either been mistaken, or he had a different understanding of what qualifies as a nucleus in tetrahedral clusters. Nor am I convinced of the significance that Fuller drew from the ratio between the 6 multiplier and the additive 0–5; The ratio of 6:5 is the same as 144:120, the volume of the spherical domain (there are 144 quanta modules in the rhombic dodecahedron), and the Basic Disequilibrium LCD Triangle (which divides the icosahedron by 120). Further, I do I see the 12:10 correlation that Fuller claimed existed between the volume of the outer shell in tetrahedra (see below), and the number of spheres in the outer layer of the VE (10F²+2). That’s not to say there isn’t one.

The formula for the tetrahedral volume of the VE is 20F³. We can isolate the shell volume by subtracting the volume of its interior VE, i.e., the VE of frequency (F-1): 20F³ – 20(F-1)³. The formula works out to be the following:

10(6F²-6F+2) = volume of outer shell (in tetrahedra) of VE of frequency F

which can be rewritten as: 10×[2+(12(F²-F)/2)].

Again, we have the same pattern, (F²-F)/2, seen in the formula for unique pairings. We also have the same ‘+2’ seen in the sphere shell growth rate formulas above. Further investigation would no doubt reveal other interesting patterns and correlations between the close packing of spheres and space-filling polyhedra.