“Starting With Parts: The Nonradial Line: Since humanity started with parallel lines, planes, and cubes, it also adopted the edge line of the square and cube as the prime unit of mensuration. This inaugurated geomathematical exploration and analysis with a part of the whole, in contradistinction to synergetics’ inauguration of exploration and analysis with total Universe, within which it discovers whole conceptual systems, within which it identifies subentities always dealing with experimentally discovered and experimentally verifiable information. Though life started with whole Universe, humans happened to pick one part, the line, which was so short a section of Earth arc (and the Earth’s diameter so relatively great) that they assumed the Earth-scratched-surface line to be straight. The particular line of geometrical reference humans picked happened not to be the line of most economical interattractive integrity. It was neither the radial line of radiation nor the radial line of gravity of spherical Earth. From this nonradial line of nature’s event field, humans developed their formulas for calculating areas and volumes of the circle and the sphere only in relation to the cube-edge lines, developing empirically the “transcendentally irrational,” ergo incommensurable, number pi (π ), 3.14159 . . . ad infinitum, which provided practically tolerable approximations of the dimensions of circles and spheres.”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 982.20

It would seem that conventional 90° geometry has the advantage over Fuller’s 60° geometry in that the area of the circle in squares is stated simply as πr², while its area in equilateral triangles is the more cumbersome π4r²√3/3. But remember that the r in the equation is the circumradius of a very high frequency polygon, and not the midradius assumed by pi.

The simplicity of the formula in 90° geometry is due to the coincidence that the midradius of the unit square is identical with the square’s edges. In fact, this may be why we ended up with a 90° geometry in the first place, and not, as Fuller believed, because we thought the Earth was flat.

The same is true for volumes. The mid-sphere radius of the unit cube is identical with its edges and leads to the relatively simple formula, 4/3 × πr³, as opposed to its 60° equivalent, 6√2 × πr³.

Conversion Factors and Power Constants

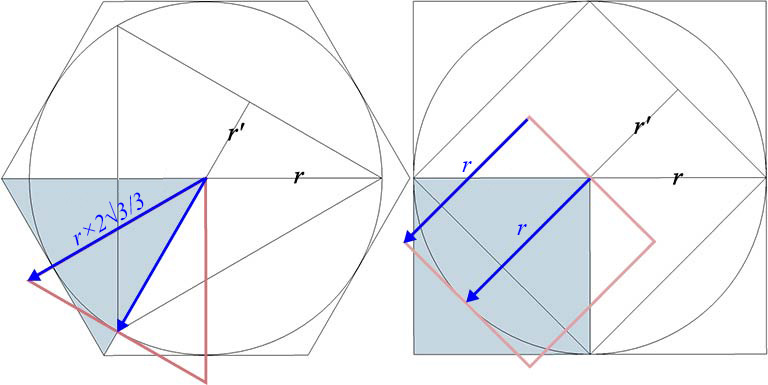

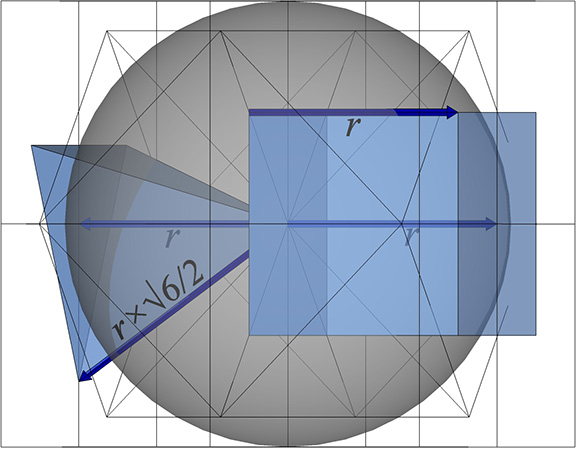

The difference between the midradius and the triangle’s edge accounts for the multiple of 2√3/3 for heights and radii in the 60° formula for areas. The difference between the mid-sphere radius and the tetrahedron’s edge accounts for the multiple of √6/2 for heights and radii in the 60° formula for volumes. See: Areas and Volumes in Triangles and Tetrahedra.

If we divide the 60° area of the circle (in triangles) by its 90° area (in squares), we get my 60° conversion factor for areas, 4√3/3. And if we divide the 60° volume of the sphere (in tetrahedra) by its 90° volume (in cubes), we get my 60° conversion factor for volumes, 6√2. These conversion factors are simply the inverses of the conventional area (in squares) and volume (in cubes) of the equilateral triangle and the regular tetrahedron. The area (in squares) of an equilateral triangle of unit edge length is: 1/2 × base × height = 1/2 × √3/2 = √3/4, and the inverse of √3/4 is 4/√3, or 4√3/3.

Area (in equilateral triangles) = Area (in squares) × 4√3/3 ≈ 2.30940108

The cubic volume of the regular tetrahedron of unit edge length is: 1/3 × base × height = 1/3 × √3/4 × √6/3 = √2/12, and the inverse of √2/12 is 12/√2 = 6√2.

Volume (in regular tetrahedra) = Volume (in cubes) × 6√2 ≈ 8.48528137

See also: General Unit Conversions.

Fuller’s Synergetics Power Constants

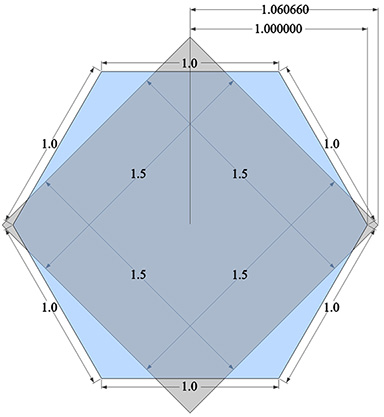

“Synergetics has discovered that the vectorially most economical control line of nature is in the diagonal of the cube’s face and not in its edge. […] The isotropic-vector-matrix’s field-occurring-cube’s diagonal edge has the value of 2, being the line interconnecting the centers of the two spheres. […] The square root of 2 = 1.414214, ergo, the length of each of the cube’s edges is 1.414214. […] Therefore, the cube occurring in nature with the isotropic vector matrix, when conventionally calculated, has a volume of 2.828428. […] This same cube in the relative-energy volume hierarchy of synergetics has a volume of 3, [and] 3 ÷ 2.828428 = 1.06066. To correct 2.828428 to read 3, we multiply 2.828428 by the synergetics conversion constant 1.06066.”

—R.Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 982.21-46 (condensed)

The first appearance of Fuller’s synergetics power constants is in a paper he published in 1950 called the Dymaxion Hierarchy of Vector Generated Field-, Volume-, Mass-, Charge-Potential of Geometric Forms. It was Fuller’s first exposition of his “Dynamic Energetic Geometry,” later to be renamed Synergetics. The paper was republished, without modification, as Table 963.10, in Synergetics I. It includes the first mention of the “A particle,” which will become his A quanta module, and the “Dymaxion,” which will become his vector equilibrium (VE). It is also the first mention of his discovery for the rational volumes of the cube, octahedron, rhombic dodecahedron, VE, and Kelvin’s truncated octahedron.

The synergetics power constants and their applications can be confusing and require, I think, some explanation. What Fuller would later call his synergetics conversion constant is referenced in Table 963.10 as a mathematical derivation of the dymaxion vector constant, or “V”. The synergetics conversion constant is the factor he uses to convert conventional (or cubic) volumes to their “energetic” volumes, while the dymaxion vector constant is two times its third root. In other words, the dymaxion vector constant is 2 times the 1st power synergetics constant which is multiplied by itself to produce the synergetics power constants for the 2nd, 3rd, and higher dimensions.

The synergetics power constants are:

1st power constant: ⁶√(9/8) ≈ 1.019824451328

2nd power constant: ³√(9/8) ≈ 1.040041911526

3rd power constant: √(9/8) ≈ 1.060660171780

4th power constant: ³√((9/8)²) ≈ 1.081687177731

5th power constant: ⁶√((9/8)⁵) ≈ 1.103131032537

6th power constant: 9/8 = 1.125

9th power constant: ²√((9/8)³) ≈ 1.193242693252

12th power constant: (9/8)² = 1.265625

Fuller’s synergetics conversion constant for volumes is the third power constant, arrived at by dividing the vector-diagonal cube’s “energetic” volume of 3 by its conventionally calculated cubic volume of 2√2.

synergetics conversion constant = 3/(2√2) = 3√2/4 = √(9/8) ≈ 1.060660172

The cube’s energetic volume is 3, a number familiar to readers as the tetrahedral volume of the unit-diagonal cube. But this is inconsistent with the cubic volume in the denominator, which assumes a diagonal twice the length. Careful reading, however, shows that the cube’s “energetic” volume, is not the tetrahedral volume of a unit diagonal cube but, rather, the cubic volume of a cube whose diagonal length is “V,” i.e., two times the 1st power constant.

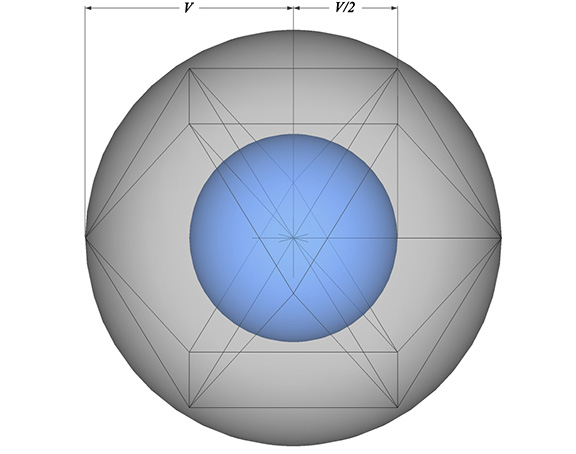

dymaxion vector constant, V = 2 × ⁶√(9/8) = ³√(6√2) ≈ 2.039648903

The “energetic” volume of the cube in the numerator of his synergetics conversion constant is the cubic volume calculated with a diagonal length of V, while the conventional volume of the cube in the denominator is the cubic volume calculated with a diagonal length of 2. The “energetic” volume (in cubes) is numerically identical with the tetrahedral volume (in tetrahedra) of a unit-diagonal cube.

Note: In Fuller’s geometry, the edges of polyhedra (or, sometimes, their diagonals) are vectors connecting sphere centers. If the radius of those spheres is taken to be unity, the vectors connecting the sphere centers must have a length two times their radius, or ‘2’. This explains why his conventionally-calculated volume of the vector-diagonal cube assumes the edges to be of length √2 rather than √2/2. On the other hand, the conversion constant I calculated above (6√2) assumes a vector length of 1. Fuller’s insistence on doubling the edge length in his cubic calculations has merit. After all, conventional geometry already assumes a vector length of 2 when it assigns a radius length of 1 to its prime sphere. It is why the circumference of the circle is 2πr rather than πd, and why cyclical unity (360°) is 2π radians.

Fuller’s primary aim with his synergetics power constants was to resolve all of the mathematical and physical constants (pi, Planck’s constant, etc.) into whole numbers or simple fractions aligned with the rational 60° coordinate system of the isotropic vector matrix. But he left it to others to work out the details. His own attempts were either flawed or unpersuasive. He proposed a whole number value for Planck’s constant (20), and at one point believed he’d succeeded in finding a rational volume for the sphere (5). He later retracted this claim, writing, “My hindsight wisdom tells me that my subconscious demon latched tightly onto this 5 and fended off all subconsciously challenging intuitions.” The “5” that his subconscious demon had latched onto is almost (but not precisely) the cubic volume of the sphere multiplied by his synergetics conversion constant raised to the 3rd power: cubic volume of sphere × (synergetics conversion constant)³ = 4π/3 × (3√2/4)³ ≈ 4.9983. He later realizes he had raised to the third power what was already his third power constant, thereby inadvertently calculating the “energetic” volume of the sphere using the 9th power constant. Had he used the 3rd power constant, the result would have been 4π/3 × 3√2/4 ≈ 4.4429—a number sufficiently distant from 5 so as not be mistaken for a rounding error due to the lack of “absolute resolvability of trigonometric calculations.” The rational value of 20 which he proposed for the Planck constant is based on the observation that its base value of 6.626070 approximates the ratio of the tetrahedral volumes of the VE and the cube.

Volume of VE ÷ Volume of Cube = 20/3 = 6.666…

The difference between 6.626070 and 6.666666 was, he believed, due entirely to our clumsy system of measurement and the units employed, a dubious claim that has mostly been ignored.

In his calculations for the cubic volume of the sphere, Fuller assumes a radius of 1, i.e. half the sphere’s diameter which has a vector length of 2. If we were instead to use my conversion constant for volumes, 6√2, rather than Fuller’s, we would need to calculate the sphere’s cubic volume using a radius of 1/2:

4π/3 × (1/2)³ × 6√2 = π√2 ≈ 4.4429

We can calculate the “energetic” (or tetrahedral) volumes of the sphere directly using Fuller’s dymaxion vector constant, V. In the figure below, the energetic volume of the blue nuclear sphere is 4/3 × π(V/2)³ = πV³/6 ≈ 4.442883. The circumsphere of the VE, the gray sphere in the figure below, has an energetic volume of 4πV³/3 ≈ 35.543064.

The 3rd root of my conversion constant for volumes, i.e., ³(6√2), is identical with Fuller’s dymaxion vector constant, V. That is, 2 × ⁶√(9/8) = ³√(6√2). In section 985.02 of Synergetics I, Fuller briefly mentions the conversion constant for areas I calculated above, 4√3/3, and applies it to the square area of unit circle, but he does not relate it to his other power constants. If we take the 2nd root of my conversion constant for areas, i.e. √(4√3/2), and apply it as the unit vector for calculations of area, the equilateral triangle has a square area of 1, the hexagon has a square area of 6, etc.

Some Coincidences and Curiosities

There may be more to Fuller’s, and my own, power constants, and I’ll circle back to this topic as fresh insights emerge. If science is to make the transition from the 90° to the 60° system of measurement and geometric modelling, the power constants, or some version of them, would seem to be relevant to the process. For now, the following coincidences and curiosities may lead me somewhere, or they may be mathematically trivial.

If we apply my 2nd power conversion constant for areas to the edge of an equilateral triangle, its area (in squares) is numerically identical to its edge value.

1/2 × base × height = 1/2 × 4√3/3 × (√3/2 × 4√3/3) = 4√3/3 ≈ 2.309401077

Fuller’s 3rd power constant is equal to the ratio of my conversion factors for heights and radii in two and three dimensions:

√6/2 ÷ 2√3/3 = 3√2/4 ≈ 1.060660172

The dymaxion vector constant (V) raised to the third power is equal to my conversion constant for volumes, 6√2, just as the third root of my conversion constant for volumes in identical with V.

V³ = 6√2 ≈ 8.485281374

My conversion constant for volumes, 6√2, is eight times the synergetics conversion constant:

6√2 ÷ 8 = 3√2/4 ≈ 1.060660172

A square with a perimeter of 6 has a radius equal to the synergetics conversion constant.

The dymaxion vector constant (V) raised to the second power is equal to the third root of 72.

V² = 2×(³√9) = ³√72 ≈ 4.1601676461

It may be only a coincidence that the prime cube consists of exactly 72 quanta modules.

A rhombic dodecahedron with a short diagonal length of √6/2—my conversion factor for heights and radii in three dimensions—has an edge length of 3√2/4, the synergetics conversion constant.