The regular icosahedron has an irrational volume in both cubes and tetrahedra. Fuller accounted for this irrationality by noting that the icosahedron exists only as discrete shells and lattices; it does not close pack, either with itself or any other regular polyhedron to fill all space. Nature, therefore, had no need to assign it a volume commensurate with any of the other regular polyhedra.

Its isolation is further reinforced by its axes of spin and the 31 great circles they describe. No great circle unique to the icosahedron passes through any point of contact with spheres radially close-packed in the isotropic vector matrix. Six of its great circles pass through no points of contact, including those between spheres arranged into icosahedral shells and lattices. This isolation suggests the icosahedron to be a model for potential energy, charge, and other holding patterns of energy.

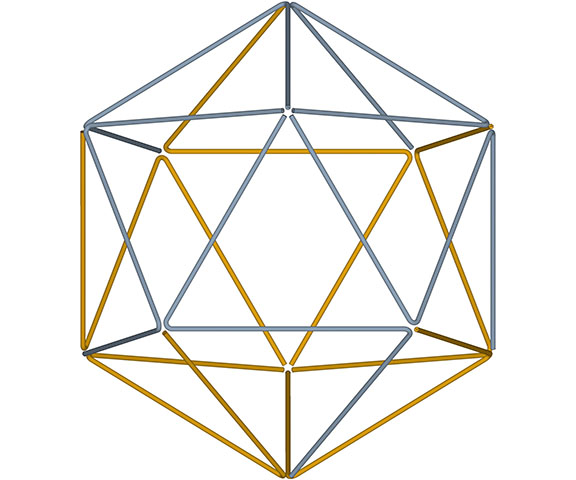

The icosahedron of edge length a has the following properties:

- φ=golden ratio, (1+√5)/2)

- Face angles: all 60°

- Dihedral angle: acos(-√5/3) or 180°-asin(2/3) ≈ 138.189685°;

- Central angle of edge: atan(2) ≈ 63.434949°

- Volume (in tetrahedra): a³×5φ²√2 ≈ 18.512296

- Cubic volume: a³×5φ²/6 ≈ 2.18169499

- A and B quanta modules: n/a

- Surface area (in equilateral triangles): 20a²

- Surface area (in squares): 5a²√3

- In-sphere radius: a×φ²√3/6 ≈ 0.755761

- Mid-sphere radius: a×φ/2 ≈ 0.809017

- Circum-sphere radius: a×(√(φ+2))/2 ≈ 0.9510565

If the nucleus is removed from a radially close-packed cluster of 13 unit radius spheres (see Vector Equilibrium and the “VE”), the remaining 12 spheres naturally rearrange themselves into the stable configuration of the icosahedron.

The icosahedron is famously derived from the golden ratio (φ), i.e., by connecting the vertices of three golden rectangles arranged orthogonally around a common center.

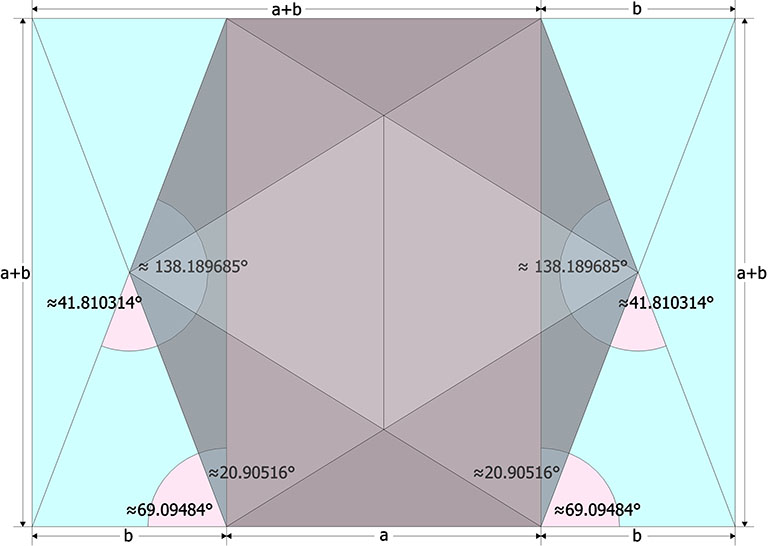

The following illustration shows how the dihedral angles of the regular icosahedron relate to the golden ratio.

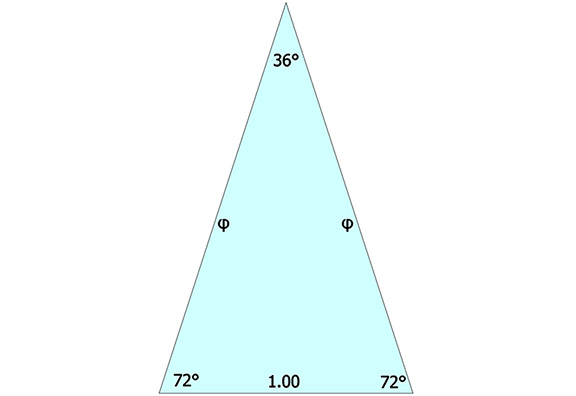

The icosahedron’s circumsphere and mid-sphere radii are the cosines of 18°, (√φ+2)/2, and 36°, φ/2, or the sines of 72° and 54°. The angles 72° and 36° define the golden triangle.

The two angles of the golden triangle are formed in the icosahedron by a lines drawn perpendicular to the circumsphere or mid-sphere radii and intersecting with a sphere of unit radius, disclosing the relationship between the icosahedron, the unit-radius sphere, and the vector equilibrium (VE).

The 36° and 72° angles also show up in the face angles of the polyhedron that complements the icosahedron in the jitterbug transformation, i.e., when the VEs have contracted into the shape of the regular icosahedron, the octahedra have expanded into the shape of its complement, and vice versa. (See: Icosahedron Phases of the Jitterbug.)

The concave forms of the regular icosahedron and its space-filling complement have, despite their different shapes, identical face angles: eight equilateral triangles (60°, 60°, 60°) and twelve isosceles triangles of 36°, 36°, 54°.

We can close up the cavities to create six irregular tetrahedra arranged orthogonally around their common centers. Curiously, the tetrahedral cavities of both the regular icosahedron and its complement have identical, rational cubic volumes of a³/12, or a combined cubic volume of a³/2, where a is the edge length.

The in-sphere radius makes an angle with the mid-sphere radius of atan(2-φ), or about 20.905157°. Some tedious trigonometry works out its length to be φ²√3/6 or about 0.75576131.

The central angle, i.e. the angle between two adjacent vertices of the icosahedron and its center of volume, is the same as the angle from a square’s mid-edge to one of its opposite corners, atan(2), about 63.43894882°.

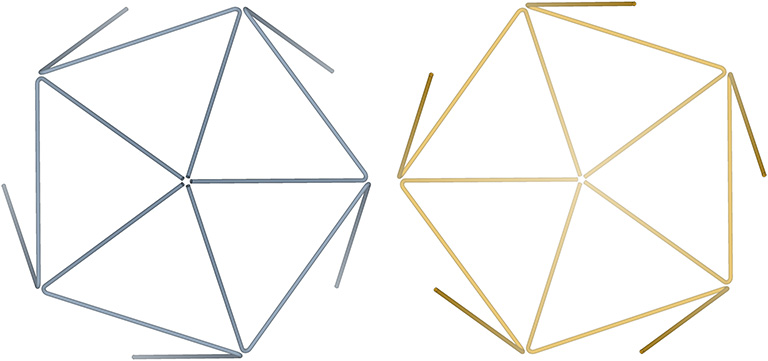

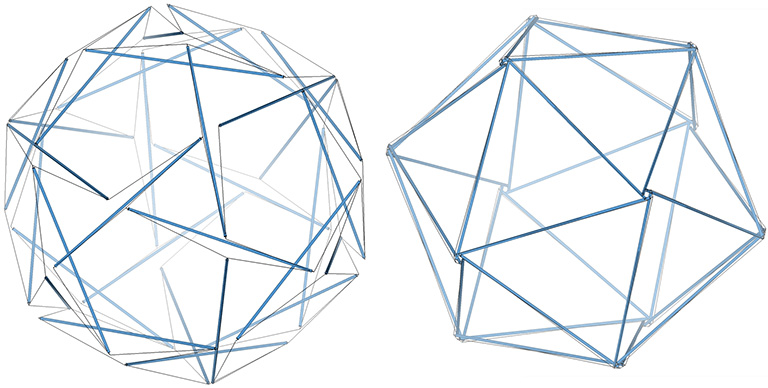

Fuller sometimes referred to the six-strut tensegrity sphere as the “tensegrity icosahedron.” Mathematicians are now calling it the Jessen Orthogonal icosahedron. See: Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron and Tensor Equilibrium, and The Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron in the Isotropic Vector Matrix. It would be perhaps more accurate to say that it approximates the shape of an octahedron (eight triangles, with six vertices meeting at mid-strut). But I prefer to call it “the tetrahedron in its tensor equilibrium phase.” It is also the shape that the VE and octahedron describe precisely midway through the jitterbug transformation of the isotropic vector matrix. See: Tensegrity; Tensegrity Equilibrium and Vector Equilibrium; Jitterbug, and; Icosahedron Phases of the Jitterbug.

The regular icosahedron in its tensor equilibrium phase (left in the figure below) approximates the shape of the icosidodecahedron.

The icosahedron has an irrational volume and so is incommensurate with the A and B quanta modules.

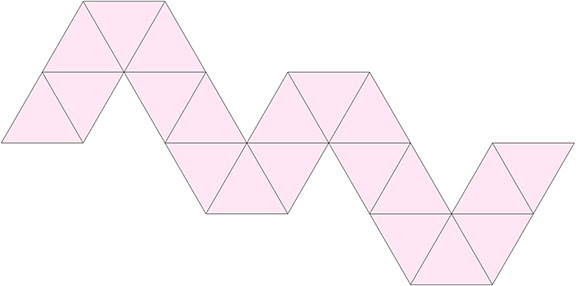

The regular icosahedron can be constructed from a single paper strip of twenty equilateral triangles.

The construction is accomplished by 19 sequential folds of atan(2√5/5).

The Raleigh Edition of the Dymaxion Airocean World Map (copyright 1954) is a variation of the cartographic projection method Fuller patented in 1946. Earth’s surface is mapped onto the planar facets of the regular icosahedron by a method Fuller called “triangular geodesics transformational projection.” It is one of the most distortion-free maps of the earth’s surface every devised. Great circles approximate straight lines, and its modules can be rearranged to reveal relationships and orientations not otherwise apparent on more conventional maps.

The map folds neatly into a regular icosahedron.

All the structural (i.e. triangulated) polyhedra may be constructed from an even number triangular helices, or what Fuller called one half of a structural quantum. The tetrahedron and icosahedron (but not the octahedron) require an equal number of clockwise and counter-clockwise helices.

The two helices each occupy their own hemisphere, with exclusively clockwise helices in one hemisphere, and exclusively counter-clockwise helices in the other. Each radiate from diametrically opposed vertices, in effect polarizing the icosahedron on one preferred axis of spin. See also: Isotropic Vector Matrix as Transverse Waves.)