“The tetrakaidecahedron (Lord Kelvin’s “Solid”) is the most nearly spherical of the regular conventional polyhedra; ergo, it provides the most volume for the least surface and the most unobstructed surface for the rollability of least effort into the shallowest nests of closest-packed, most securely self-cohering, allspace- filling, symmetrical, nuclear system agglomerations with the minimum complexity of inherently concentric shell layers around a nuclear center.“

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 942.70

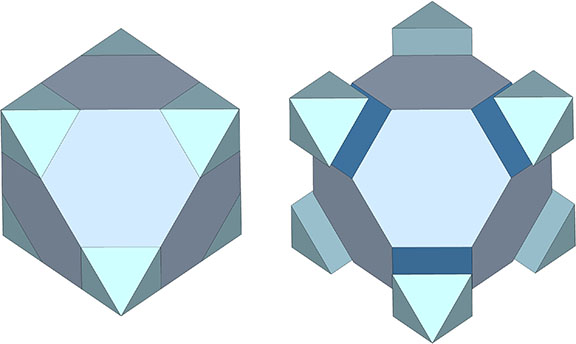

The Kelvin truncated octahedron, or Kelvin, is a space-filling, fourteen-sided polyhedron with eight hexagonal faces and six square faces, all of equal edge-length. It got its name from a problem posed by Lord Kelvin in the 19th century, to find an arrangement of cells of equal volume so that their total surface area is minimized.

Note: Fuller refers to this shape as the tetrakaidecahedron, a generic term for all 14-sided polyhedra. I reserve this term for the all-space filling complement to the pyritohedron in the Weire-Phelan matrix. See Tetrakaidecahedron and Pyritohedron.

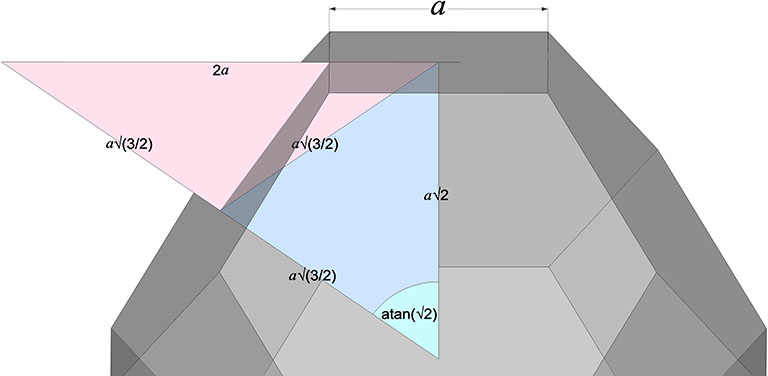

Angles and dimensions of the Kelvin tetrakaidecahedron or truncated octahedron with edge length a:

- 14 faces (8 hexagonal and 6 square), 24 vertices, 36 edges

- Face angles: 90°, 120°, 120°

- Dihedral angle: arccos(-√3/3) ≈ 125.264390°

- Central angle of edge: atan(3/4) ≈ 36.869898°

- Volume (in tetrahedra): 96a³

- Volume (in cubes): 11a³√2

- A quanta modules: 1,536

- B quanta modules: 768

- Surface area (in equilateral triangles): 8a²(6+√3)

- Surface area (in squares): 6a²(1+2√3)

- In-sphere radius (center to mid-hexagonal-face): a√(3/2) = a√6/2

- In-sphere radius (center to mid-square face): a√2

- Mid-sphere radius (center to mid-edge): 3a/2

- Circumsphere radius (center to vertex): a√(5/2)

Fuller noted that the Kelvin defined nuclear domains in the radial close-packing of unit-radius spheres.

Presently the best solution to the Kelvin problem is the Weaire-Phalen matrix, consisting of pyritohedra and tetrakaidecahedra. Perhaps not surprisingly, the Kelvin can be derived from from this matrix. Connecting radials of the tetrakaidecahedra forms the very same Kelvin as above. Its edges are of unit-length, the same as the spheres’ diameters.

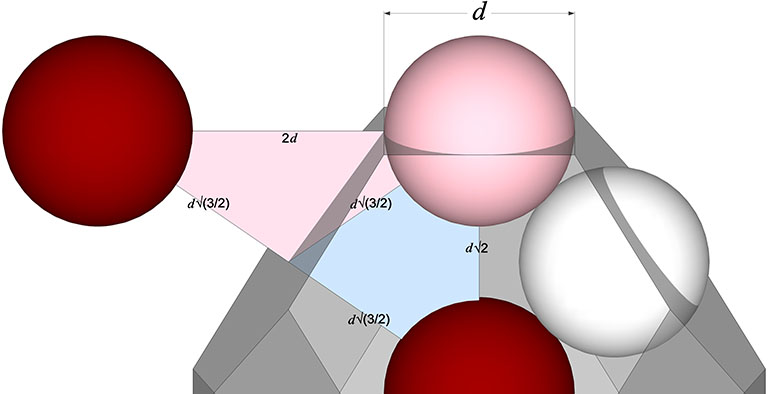

It may be easier to see how the Kelvin faces are derived from the radials of the tetrakaidecahedron if we examine one of its square faces and one of its hexagonal faces individually. The pink spheres in the illustrations below are the non-unique nuclei, those nuclei whose shells are shared with their neighbors. See Formation and Distribution of Nuclei in Radial Close-Packing of Spheres.

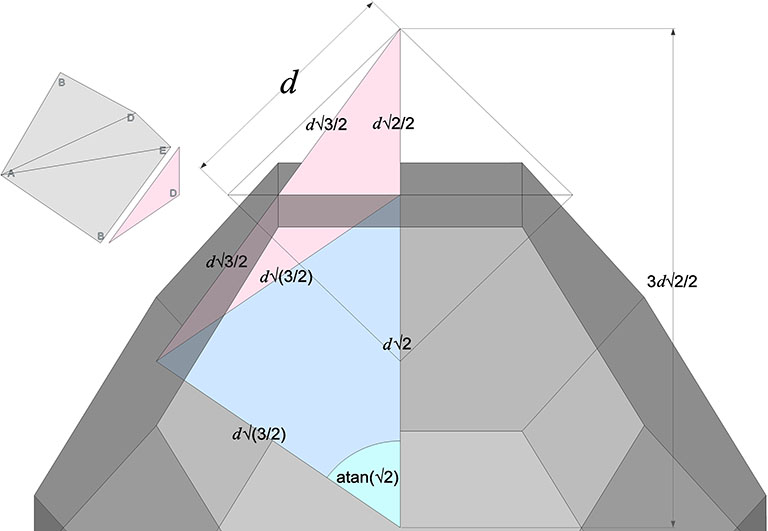

The two in-sphere radii—from center to mid-square-face, and from center mid-hexagonal-face—make an angle of arctan(√2) ≈ 54.735610° with each other. A line drawn between the mid-faces creates an isosceles triangle with a base of a√2 and sides of a√(3/2). Extending the mid-hexagon-face radius to where it crosses a line drawn perpendicular from the mid-square-face radius creates an isosceles triangle with a base of 2a (where a = edge length, unity, or sphere diameter) and sides of a√(3/2). Combining the two isosceles triangles creates a right triangle whose legs measure a√2 and 2a, and whose hypotenuse measures 2×a√(3/2) = a√6.

This triangle maps to the distribution of nuclei in the isotropic vector matrix, with unique nuclei centered on the vertices of the two non-right angles, and the nuclei that share their shells with adjacent nuclei centered on the right angle’s vertex.

Note that in the illustrations below, d = a = the sphere diameter. Unique nuclei are colored red, non-unique nuclei are pink, and the spheres occupying the shells of nuclei are white.

Extending the mid-square-face radius to a point where it crosses a line drawn perpendicular to the mid-hexagon-face radius creates a scalene triangle whose angles are curiously identical with the interior face of the B quanta module. Combining this scalene triangle with the isosceles triangle mentioned above creates a right triangle whose legs measure 2d√2/2 and d√(3/2). The mid-square-face radius extends d√2/2 beyond the face, exactly half of the face’s diagonal length, and half the mid-square-face radius. This suggests a rotational transformation of the Kelvin that may shadow the space-to-sphere, sphere-to-space transformations of the isotropic vector matrix, something begging to be investigated further, along with that curious appearance of the interior face of the B quanta module (pink in the illustration below).

If we replace the twelve vertices of a one-frequency Kelvin with spheres, we find that they occupy the spaces between the 42 spheres of the two 2-frequency vector equilibrium (VE) shell. The 2-frequency VE is significant because its shell is the last to fully enclose the nucleus without containing any new potential nuclei. The 1-frequency Kelvin complements the 2-frequency VE to fully isolate unique nuclear domains.

Kelvins with even frequencies (odd numbers of spheres to the side) are coincident with the radially close-packed spheres of the isotropic vector matrix. Those with odd frequencies (even numbers of spheres to the side) occupy the spaces between radially close-packed spheres.

At the center of odd Kelvins is a space, i.e., concave VE, and at the center of even Kelvins is a sphere. Note that the odd Kelvins in the above examples which fully isolate the nucleus have been shifted by 1/2 of a sphere diameter out of their natural position in the matrix. (See also: Spaces and Spheres (Redux), and; Spheres and Spaces.)

In the figures below, spheres and spaces are represented by the two quanta module constructions of the rhombic dodecahedron.

Fuller conceived the Kelvin as a truncated tetrahedron…

…and associated it with his Seven Axes of Symmetry.

Fuller’s conception of the Kelvin as a truncated tetrahedron, rather than a truncated octahedron, is perhaps due to its association with the spherical form of the tensegrity tetrahedron, the six-strut tensegrity sphere or Jessen Orthogonal Icosahedron.