“The geometrical model of energy configurations in synergetics is developed from a symmetrical cluster of spheres, in which each sphere is a model of a field of energy all of whose forces tend to coordinate themselves, shuntingly or pulsatively, and only momentarily in positive or negative asymmetrical patterns relative to, but never congruent with, the eternality of the vector equilibrium. “

— R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, section 205.01

Vectors connecting the centers of unit-radius spheres clustered around a common nucleus define the VE, or vector equilibrium.

In the VE, the number of modular subdivisions, i.e. frequency, of the radii is exactly the same as the number of modular subdivisions of the chords. Frequency may refer, then, to the number of shells surrounding the nucleus or to the number of subdivisions of any edge vector.

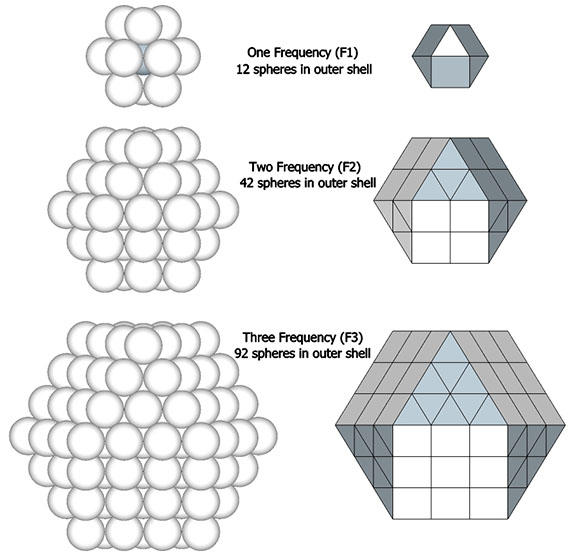

The radial close packing of equal radius spheres about a nuclear sphere forms vector equilibria of progressively higher frequencies. The number of spheres in the outer shell is always the frequency (F)—the number of subdivisions of the radial or edge vectors running through the sphere centers—raised to the second power, which is then multiplied by ten, then added to two, or 10F²+2. In the illustration below, the F1 VE (with unit radial and edge vectors) has twelve spheres in its outer shell: (10×1)+2=12. The F2 VE (whose radial and edge vectors have been divided into two subdivisions) has 42 spheres in its outer shell: (10×2²)+2=42. The F3 VE (with three subdivisions) has 92 spheres in its outer shell: (10×3²)+2=92.

Shell Volume (in spheres or vertices) of VE = 10F²+2

The cumulative number of spheres in a radially close-packed array is therefore:

10(F12+F22+F32+ … +Fn2)+2Fn+1,

which integrates to:

(20F3+30F2+22F+6)/6

The polyhedral shape of these nuclear assemblages of closest-packed spheres is always that of the vector equilibrium, having always six square, and eight triangular faces, for a total of fourteen. The square faces are the equatorial sections of six half-octahedra, and the triangular faces are the bases of eight tetrahedra. If the tetrahedron is taken as unity, the volume of the vector equilibrium is twenty (20). The volume in tetrahedra of any series of vector equilibria of progressively higher frequencies is always frequency to the third power times 20.

Volume (in tetrahedra) of VE = 20F³

The VE is the only construction of radially close-packed spheres that produces uniform and uninterrupted layers. Radial close-packing as octahedra is achieved only with even-numbered layers (odd numbered layers are centered on spaces), and radial close packing as tetrahedra and cubes is achieved only with every other even layer (odd numbered layers are centered on either a positive or a negative tetrahedron, and every other even layer is centered on a space).

In A and B quanta modules, the VE of frequency, F, equal to 1 consists of 336 A quanta modules and 144 B quanta modules for a total of 480 quanta, a volume of 480÷24=20 tetrahedra.

The polyhedron associated with the external shape of the VE is conventionally recognized as the cuboctahedron, or the truncated cube. That its edge lengths are identical to the length of its circumsphere radii was perhaps less well known, and its association with the radial close-packing of unit-radius spheres was either unknown or dismissed by mathematicians as of peripheral interest. For Fuller, these characteristics were central to his search for the geometric analog to his more general statement of Avogadro’s proposition, that under under identical, unconstrained, and freely self-interarranging conditions of energy all elements will disclose the same number of fundamental somethings per given volume. This was discovered to be his octet truss, or isotropic vector matrix, and the vector equilibrium (VE) is its metonymous form.

The question of structure, too, has historically been peripheral to the study of pure geometry; the subject was left to the engineers, and the engineers had for millennia been mostly stone masons for whom one geometric shape was as solid as the next. Fuller’s octet truss and geodesic structures were unknown until the “space age” of the mid-twentieth century. In the absence of its radial vectors, the remaining circumferential (edge) vectors of the cuboctahedron are left unsupported and will collapse, just as the vector model of the cube it was based on will collapse without additional triangulation. Neither is structural, if by “structure” we mean something that holds its shape without external support. In the absence of gravity and the solid earth beneath them, few man-made structures fit this definition.

A third point of contention that Fuller had with conventional geometry was its attention to linear growth and parallel lines, which he attributed to our flawed notion of a flat earth that extended to infinity, and a single direction for “up,” the equal and opposite direction of our “down-to-earth” sensibilities. Nature, if unconstrained, prefers radial (outward-inward) growth with circumferential (precessional-perpendicular) constraints.

The 12-strut tensegrity sphere approximates the overall shape of the VE, and perfectly models what Fuller meant by this. Like all his tensegrities, its structural integrity is maintained by a balance between the radial compression of its struts, and the circumferential tension of its tendons. The twelve-strut tensegrity sphere will torque naturally into the tensegrity octahedron, a transformation recapitulated in the vector model of the jitterbug.

The VE consists of four great circles, i.e., four 3-strut triangles in the twelve-strut tensegrity sphere, or four hexagons in the vector model.

It is likely no coincidence that the surface area of the sphere is equal to the combined surface areas of the VE’s four great-circle disks. The two sides of each disk account for both the convex external surface of the sphere and its concave internal surface. (See: Anatomy of a Sphere.) In the bow-tie construction of the VE, produced by folding the great circle disks along the VE’s central 60° angles, both surfaces are exposed, one inside the square faces, the convex, energy-dispersing surface, and the other inside the triangular faces, the concave, energy-focusing surface. This interpretation of the bow-tie model is strengthened by the quanta model in which the square faces expose the energy-dissipating B modules, and the triangular faces expose the energy-conserving A modules. (See: A and B Quanta Modules.)

The Seven Axes of Symmetry common to all the regular polyhedra correspond to the 4 axes of spin running through the VE’s eight triangular faces, plus the 3 axes running through its six square faces, the former disclosing spherical VE and its four great circles, and the latter disclosing the spherical octahedron and its three great circles.

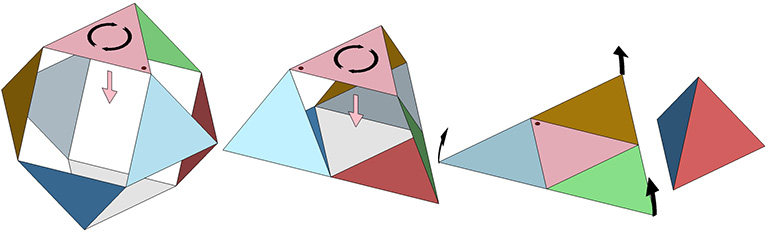

Transformations of the VE disclose the regular icosahedron, the Jessen icosahedron (or six-strut tensegrity sphere), the regular octahedron, and the regular tetrahedron. The transformation to the regular icosahedron is perhaps best modeled in the radial close packing of spheres. With the removal of the central sphere, the twelve remaining spheres naturally reposition themselves into the shape of the icosahedron.

The transformation to the Jessen orthogonal icosahedron is perhaps best modeled in the jitterbugging of the six-strut tensegrity, or tensegrity tetrahedron which, in its most relaxed, spherical, or equilibrium state is identical with the Jessen icosahedron.

The transformation to the regular octahedron is disclosed through torquing of the 12-strut tensegrity (see above), but is perhaps most convincingly modeled in the jitterbug transformation by the coordinated rotations of its eight triangular faces.

The transformation of the VE into the regular tetrahedron can be accomplished in the vector model by adding a 180° twist to the downward motion of the jitterbug.

But the transformation of the VE into a tetrahedron is perhaps best modeled in the six-strut tensegrity sphere (aka Jessen icosahedron) which occurs at the precise midpoint of the jitterbug transformation. (See: Icosahedron Phases of the Jitterbug.) From here, the VE may continue its transformation into the octahedron, or it can be torqued into the shape of a regular tetrahedron. A clockwise or counter-clockwise torque will produce either a positive or a negative tetrahedron. (See: The Dual Nature of the Tetrahedron.)

For me, the most compelling model of the jitterbug transformation, which Fuller identified with wave-particle duality, the equivalence of mass and energy, the balance of disintegrative, radiational forces (compression) with integrative, gravitational forces (tension), and which he intuited as a generative metaphor for nearly everything in the physical sciences, if not for everything that is thinkable, is the following: eight, six-strut tensegrity spheres surrounding a common center, and transforming between positive and negative tetrahedra.

This model is illustrated below, with four of the eight, six-strut tensegrity spheres torquing clockwise to form the positive tetrahedron, and the other four torquing counter-clockwise to form the negative tetrahedron, which then switch roles to reverse the process. The result is an oscillation between the VE, with the eight tetrahedra all sharing a common vertex at its center, and the octahedron, with the eight tetrahedra projecting from its eight faces. In the context of the isotropic vector matrix, all the vertices of all the tetrahedra always converge on the center of a VE, but these convergences shift by one-half wavelength with each cycle, exchanging the nuclear spheres (vertex convergences) at the centers of the VEs, with the nuclear space at the centers of the octahedra. (See also: Spheres and Spaces.)