What Fuller called the “topological abundance formulas” distill topology, a complex branch of mathematics, down to a handful of relationships, including a special case of Euler’s polyhedron formula. The formula states that for any spherical polyhedron, the number of vertices (V) minus the number of edges (E) plus the number of faces (F) always equals two (2). The ‘2’ is conventionally identified as the Euler characteristic ( χ ) of the sphere:

χ = V – E + F = 2

Fuller identified the ‘2’ with the polyhedron’s axis of spin, the two poles which the formula subtracts from the total number of vertices:

faces + (vertices – 2) = edges

For example, take the following four polyhedra: the four-sided tetrahedron, the six-sided cube, the eight-sided octahedron, and the twenty-sided icosahedron.

- The tetrahedron has four faces, four vertices, and six edges: 4 faces+(4 vertices – 2) = 6 edges.

- The cube has six faces, eight vertices, and twelve edges: 6 faces+(8 vertices – 2) = 12 edges.

- The octahedron has eight faces, six vertices, and twelve edges: 8 faces+(6 vertices – 2) = 12 edges.

- The icosahedron has twenty faces, twelve vertices, and thirty edges: 20 faces + (12 vertices – 2) = 30 edges.

For more on Fuller’s interpretation of the number ‘2’ in the topological abundance formula, see, Twoness: The Multiplicative and Additive Two.

The topological abundance formula and the Euler characteristic of the sphere, “2,” is related to the 720° deficit of a polyhedron’s angular abundance compared with that of its spherical counterpart, 720° being two cycles of unity, or 360°.

the sum of all angles around every vertex = (vertices x 360°) – 720°

Using the the same four polyhedra as above:

- The tetrahedron has four vertices surrounded by three 60° triangles. 3 x 60° = 180°, 180° x 4 = 720°. Four vertices x 360° = 1440°, and subtracting 720° from 1440° we get, again, 720°.

- The cube has eight vertices surrounded by three right (90°) angles. 3 x 90° = 270°, 270° x 8 = 2160°. Eight vertices x 360° = 2880°, and subtracting 720° from 2880° we get the same 2160°.

- The octahedron has six vertices surrounded by four 60° angles. 4 x 60° = 240°, 240° x 6 = 1440°. Six vertices x 360° = 2160°, and subtracting 720° from 2160° we get 1440°.

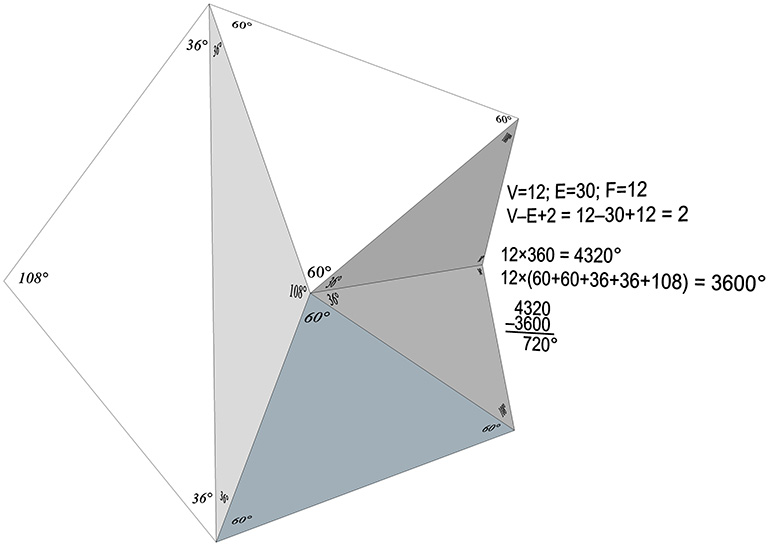

- The icosahedron has twelve vertices surrounded by five 60° angles. 5 x 60° = 300°, 300° x 12 = 3600°. Twelve vertices x 360° = 4320°, and subtracting 720° from 4320° yields, once more, 3600°.

As noted, 720° is the sum of the angles in a tetrahedron, the minimum polyhedral system. This led Fuller to state that all polyhedral systems are two cycles of unity or one tetrahedron removed from infinity. The tetrahedron has two non-polar vertices, four faces and six edges. And, in any omni-triangulated structural system, that is, for any polyhedron structurally stabilized through triangulation: the number of vertices (“crossings” or “points”) is always evenly divisible by two (2×1); the number of faces (“areas” or “openings”) is always evenly divisible by four (2×2), and; the number of edges (“lines,” “vectors,” or “trajectories”) is always evenly divisible by six (2×3). For example, the icosahedron has twelve vertices, twenty faces, and thirty edges. The number of faces is evenly divisible by two (12/2=6); the number of faces is evenly divisible by four (20/4=5); the number of edges is evenly divisible by six (30/6=5). This holds for any polyhedron of whatever size or complexity, just so long as its faces (areas, openings) are triangulated and therefore constitute a “structure” by Fuller’s definition, i.e. any system that holds its shape without external support.

The above formulas work for any polyhedron, not just the regular ones. For example, the polyhedron made from any conceivable projection of Fuller’s Basic Disequilibrium LCD Triangle would have 120 faces, 62 vertices, and 180 edges, and 62 – (180+120) = 2. All phases of the jitterbug, including those polyhedra with concave faces that comprise the icosahedron phases of the jitterbug, exhibit these regularities. All phases exhibit the same number of vertices, edges, and faces, and their surface angles all add up to 3600°.

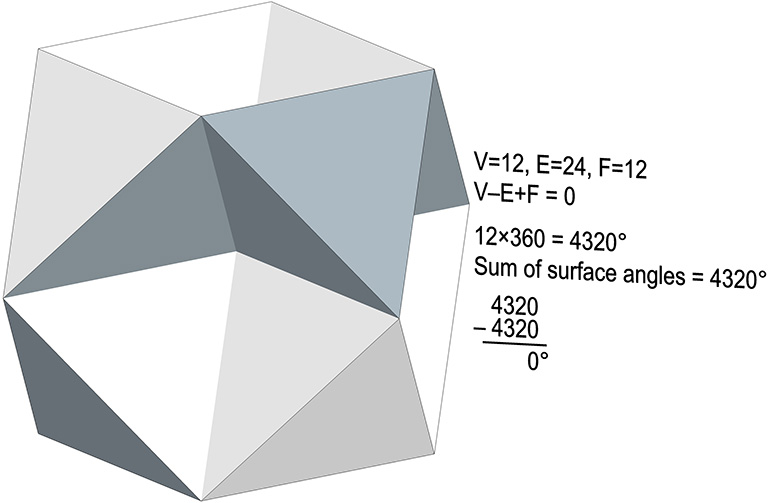

For all the icosahedron phases of the jitterbug:

V=12; E=30; F=12;

V-E+F = 12-30+12 = 2;

12×360 = 4320°;

Sum of surface angles: 3600°, and;

4320° – 3600° = 720°.

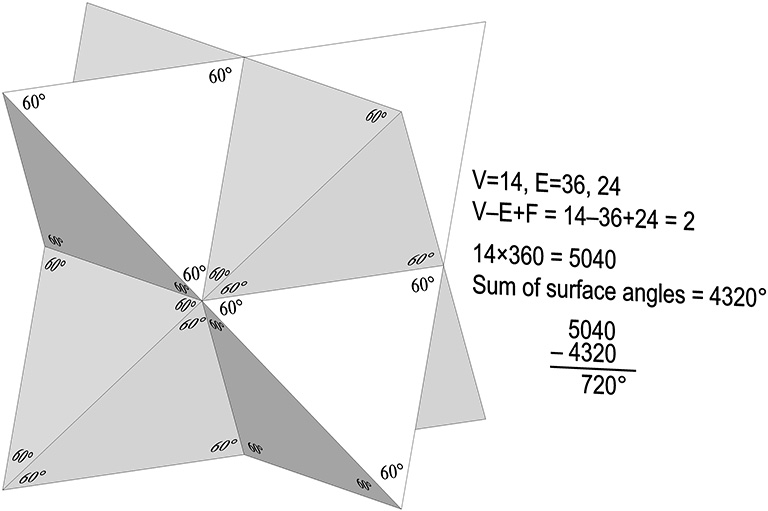

Polyhedron aggregates also seem to work. For example, a polyhedron constructed of eight tetrahedra face-bonded to an octahedron has 14 vertices, 36 edges, and 24 faces.

V=14; E=36; F=24;

V-E+F = 14-36+24 = 2;

12×360 = 4320°;

Sum of surface angles: 6(60×3)+6(60×8) = 5040°, and;

5040-4320 = 720°.

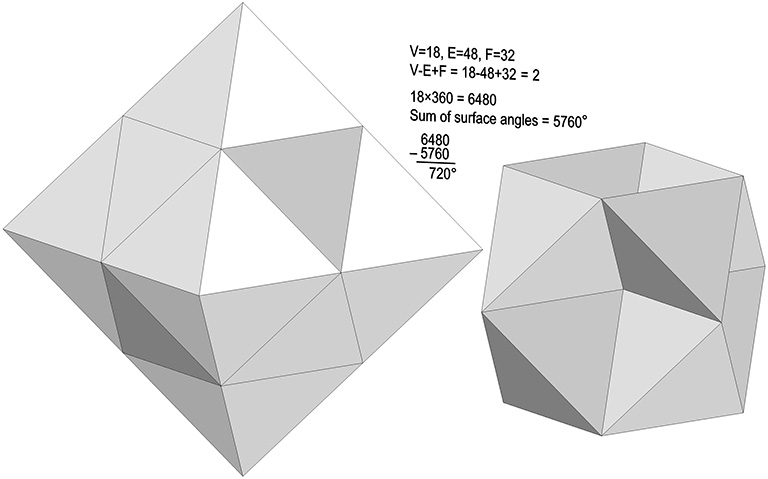

However, when we rotate those tetrahedra 90° so that they all share common vertex at the center of the VE, the formulas seem to break down. To make them work, we need to count all the edges of the eight tetrahedra, for a total of 48, and multiply the shared vertex at the center of VE by 6, making it topologically identical with the 2F octahedron.

A topological variant of the VE, the octahemioctahedron, deserves further study. Unlike the other quasiregular hemipolyhedra, the octahemioctahedron is orientable, and is topologically the equivalent of a torus. Its Euler characteristic is ‘0’, and its spherical deficit is 0°. It has 24 edges and, like the VE, eight triangular faces. But instead of six square faces its four hexagonal equatorial planes each count as one, for a total of 12 faces. The sum of the angles around each of its 12 vertices is 60+60+120+120 = 360°, and V–E+F = 12–24+12 = 0.

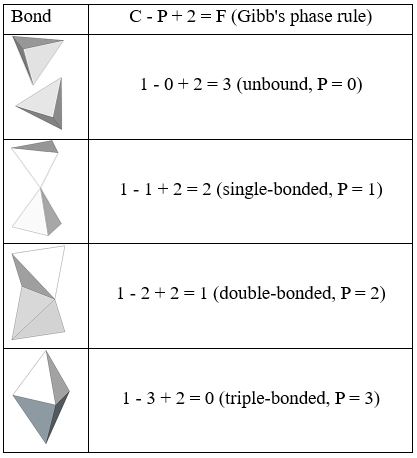

Relation to Gibb’s Phase Rule

Fuller saw a relationship between Euler’s topological abundance formula and Gibbs phase rule that goes a bit beyond the obvious. On the surface, the similarity between the two formulas is compelling. The vertices (V), edges (E), and faces (F) in Euler’s formula align neatly with the phases (P), compounds (C), and degrees of freedom (F) in Gibb’s phase rule:

V – E + F = 2

P – C + F = 2

But the relationship isn’t that simple. Phases don’t have a direct parallel in vertices, nor do compounds parallel edges, or degrees of freedom parallel faces. At least not directly.

Fuller equated the three primary phases of matter—gaseous, liquid, and water—with the bonding of polyhedra by their vertices (single bonds), edges (double bonds), and faces (triple bonds). In the following table, the degrees of freedom, F, are reduced from three (3) for unbound polyhedra where P=0, to zero (0) for triple-bonded polyhedra where P=3.

As shown in the following table, Fuller found that for any fully triangulated polyhedral system he could reduce Euler’s formula to “1 + 2 = 3” and the following three factors: the additive 2 (third column); the multiplicative 2 (4th column) and; one or more of the first four prime numbers (1, 2, 3, 5) characteristic of the polyhedral system being analyzed (fifth column). Note that the prime number in the fifth column is simply the factored reduction of the number of non-polar vertices.

As a result, Fuller proposed a revision to Euler’s formula which is a combination of the topological abundance formula and Fuller’s own formulas for sphere shell growth rates, i.e., nF²+2, with λ or μ substituting for F. The n in the growth rate formula relates to the Prime No. in the revision to Euler’s formula:

λ² -or- μ² × [Prime No.] × 2 × (1 + 2 = 3) + 2

λ = wavelength

μ = frequency – modular breakdown

For example, Fuller’s sphere shell growth rate formula for the octahedron is 4F²+2, and for F=1, Euler’s revised formula reads:

F² × [prime no.] × 2 × (1+2=3) + 2

1² × [2] × 2 × (1+2=3) + 2

= 4(1+2=3)+2

= (4 + 8 = 12) + 2

= 6 + 8 = 12 + 2 (Euler’s original formula, V+F=E+2, for the octahedron)

With Fuller’s revision of Euler’s formula, we are able to calculate the relative topological abundances of any system given a) its frequency or wavelength, i.e. number of modular subdivisions of either its radial or circumferential vectors, and b) its prime number characteristic. Its application to theoretical and experimental thermodynamics is less clear. Fuller was satisfied that he’d established a compelling geometrical correlation between “the timelessness of Euler” and “the frequency of Gibbs” (Synergetics, 1054.74), providing us with a physical model with which to conceptualize the abstract math of thermodynamics and to better understand the phase changes and equilibrium states of matter. But if Fuller adequately articulated the correlation and how to apply it, I’ve yet to disentangle it from his writings.

This topic deserves more thought and research.

Please consider, the statement “The formula states that for any spherical polyhedron, the number of edges (E) plus the number of faces (F) subtracted from the number of vertices (V) always equals two (2).”

Should it state:

“The formula states that for any spherical polyhedron, the number of edges (E) subtracted from the number of faces (F) added from the number of vertices (V) always equals two (2).”

And the expression χ = V – (E+F) = 2

Should it be: χ = V – E+F = 2, and V – χ+F = E

Good catch! I’ve removed the parentheses from the formula and changed my verbal description of the Euler characteristic. Thanks very much for pointing this out, and please let me know if you find other errors.