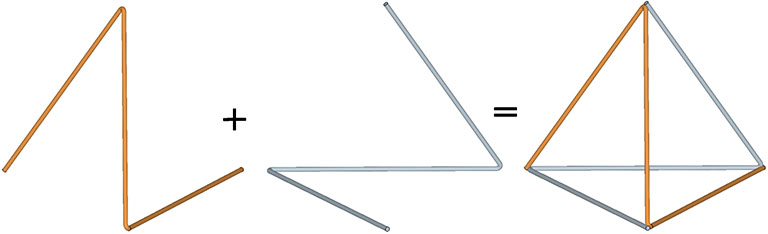

A tetrahedron may be constructed from two open-ended triangles.

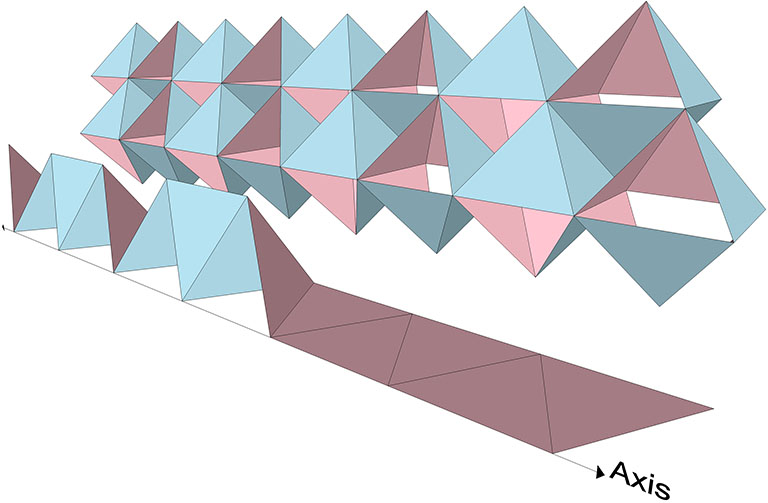

If we use this construction in the isotropic vector matrix, the open ends of each triangle join with similar triangles in the adjacent tetrahedra to form wave patterns that propagate linearly through the matrix, each oriented at 90° to the other. The entire matrix may be built though the duplication of orthogonally paired waves.

Significant to this model of the isotropic vector matrix is its demonstration of the fundamental principle that no two vectors may pass through the same point simultaneously. All vertices in the matrix redirect their vectors, rather than act as focal points for their convergence.

For each of the six axes of the isotropic vector matrix, i.e., the six vertex-to-vertex axes of spin of the vector equilibrium, there are four unique waves, two running clockwise and two running counter clockwise on either side of the axis, for a total of 24 (6×4) waves converging on and deflecting from every point.

Note that the axis that defines the linear orientation of the wave is excluded from the wave itself which traces a path along three of the remaining five edge vectors of the tetrahedron. The clockwise and counter-clockwise waves of the positive and negative tetrahedra each share one leg oriented at 90° to the wave’s directional axis, underscoring the polarization of the pair.

The six axes of the isotropic vector matrix define the six edges of the tetrahedron. The waves from these six axes wrap around each tetrahedron such that each of its six edges includes a leg from four separate waves.

This recapitulates the quadrivalent (four vectors per edge) tetrahedron that results when the jitterbug is given an extra 180° twist.

This wave pattern can also be modeled with continuous ribbons of equilateral triangles which are then folded at the same angles as the three vectors of the open-ended triangle above.

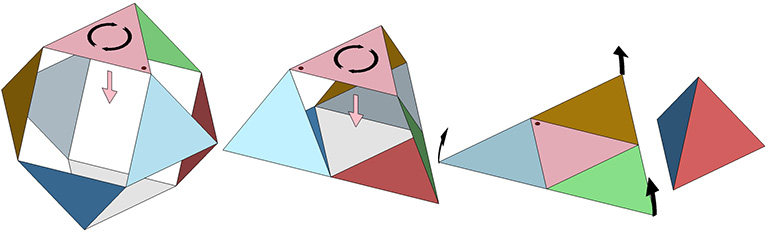

The octahedron can be constructed from four open-ended triangles.

The open-ended triangles of the octahedron may be joined in parallel linear waves that form a continuous chain of octahedra.

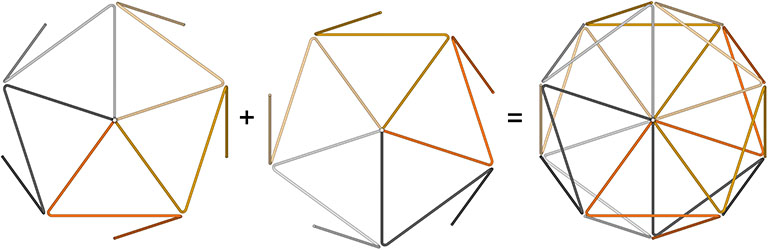

The icosahedron can be constructed from ten open-ended triangles.

There are numerous ways of joining the open-ended triangles of the icosahedron end-to-end, but all form wave-dispersal patterns in which the icosahedron appears never to repeat.