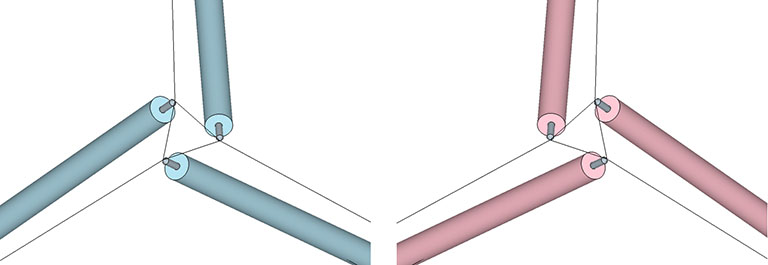

All polyhedra are either left- or right-handed and, with the exception of the tetrahedron, there is no transformation that can be modeled by which one becomes the other. The handedness of a polyhedron is not readily apparent when viewed as a solid or as a vector model with single-point vertices. However, when modeled structurally as tensegrities their handedness becomes obvious.

The tetrahedron is uniquely ambidextrous. From its relaxed state as the six-strut tensegrity sphere, it is both itself and its inverse. The transformation can go either way, producing either a positive or a negative tetrahedron. All configurations between the spherical and polyhedron phases are structurally stable, but once the choice is made to transform either in a clockwise or counterclockwise direction the ambiguity collapses into into either a positive or a negative tetrahedron. To transform back to its inverse, the tetrahedron must first pass through its spherical phase. For more information, see Tensegrity.

The Jitterbug is an oscillation between positive and negative (left-handed and right-handed, clockwise and counter-clockwise) tetrahedra.

The bow-tie construction of the rhombic dodecahedron has an extra arc along the short diagonal of each of its rhomboid faces. Removing the extra arc discloses the spherical rhombic dodecahedron as the equivalent of two tetrahedra, one positive and one negative.

For more information, see Great Circle Bow-Ties of the VE.

Turning a regular tetrahedra inside-out, i.e., forcing a vertex through its opposite face (the tetrahedron is the only regular polyhedron that can do this), produces either the star tetrahedron, or the tetrahelix, and neither close-pack to fill all-space. In fact, it’s possible that no two tetrahedra in the helical and star structures produced by serial inside-outing will ever have precisely the same orientation in a fixed coordinate system. Fuller may have attributed the difference between the tetrahedron’s mirror-image, inside-outing polarity and its rotational, axial polarity to the multiplicative (concave-convex) vs. additive (polar) duality of all polyhedral systems. (See: The Multiplicative and Additive Two.)

Perhaps a more interesting model of the tetrahedron turning itself inside out is one that results in an octahedron rather than another tetrahedron. The faces of the regular octahedron can be unfolded like the petals of flower to produce two tetrahedra, one positive and one negative with rotational (non-mirror-image) polarity. The rotation along the fold lines is exactly 180° from tetrahedron to octahedron, or from octahedron to tetrahedron. We may conclude that the octahedron is two tetrahedra turned inside out.

That the octahedron’s volume is 4 compared with the tetrahedra’s combined volume of 2 suggests a transformative model for the tetrahedron’s fundamental and inseparable duality.

Note: Fuller often remarked on the tetrahedron’s unique ability to turn itself inside out, i.e., any one of its vertices may be passed through its opposite face, thereby exchanging inside for outside like a rubber glove. For me, however, this process isn’t so much an oscillation between positive and negative tetrahedra, which is a four-dimensional phenomenon of the jitterbug transformation, but rather, a linear (or helical) phenomenon in two dimensions. See: Tetrahelix.