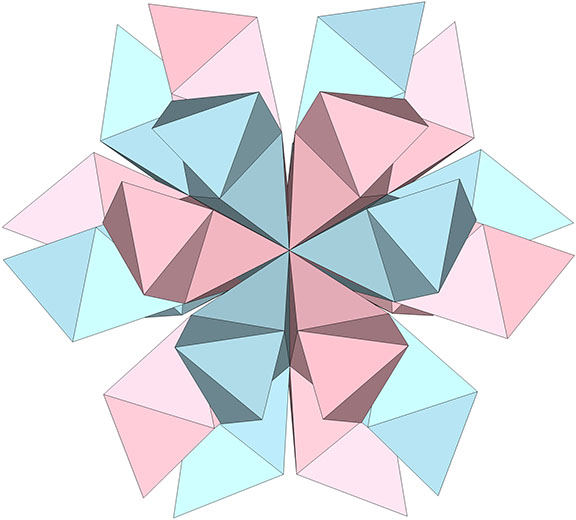

“These helical columns of tetrahedra, which we call the tetrahelix, explain the structuring of DNA models of the control of the fundamental patterning of nature’s biological structuring as contained within the virus nucleus. It takes just 10 triple-bonded tetrahedra to make a helix cycle, which is a molecular compounding characteristic also of the Watson-Crick model of the DNA. When we address two or more positive (or two or more negative) tetrahelices together, they nestle their angling forms into one another. When so nestled the tetrahedra are grouped in local clusters of five tetrahedra around a transverse axis in the tetrahelix nestling columns. Because the dihedral angles of five tetrahedra are 7° 20′ short of 360°, this 7° 20′ is sprung-closed by the helix structure’s spring contraction. This backed-up spring tries constantly to unzip one nestling tetrahedron from the other, or others, of which it is a true replica. These are direct (theoretical) explanations of otherwise as yet unexplained behavior of the DNA.”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, caption to fig. 933.01

Regular tetrahedra do not combine to fill all space. They can however be face-bonded to form a helical structure Fuller called the “tetrahelix.”

The tetrahelix can be constructed as a single, double, or triple helix, oriented either clockwise or counter-clockwise. The single helix completes about 10 cycles per 30 tetrahedra; the double helix completes about 5, and the triple helix completes about 1 cycle per 30 tetrahedra.

The single helix is folded from a ribbon of equilateral triangles, with alternating folds in the same direction of 2arctan(√2/4) ≈ 38.931629° and 2arctan(√2) ≈ 109.471221°.

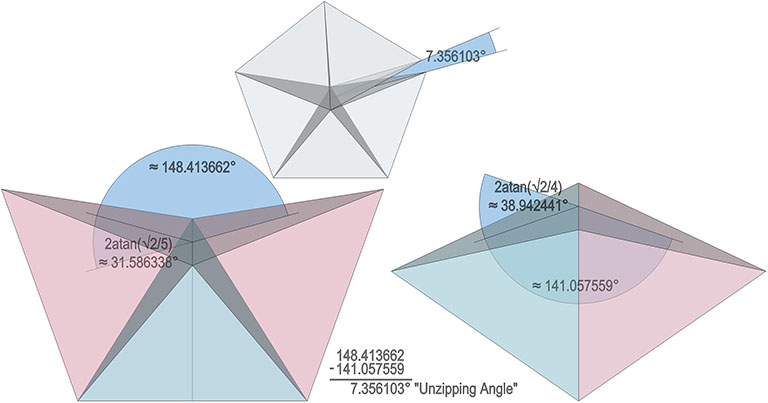

The double helix is folded from 2-panel-wide ribbon. The two panels are folded inward at 2arctan(√2/4) ≈ 38.931629°, and the individual triangles are folded in an alternating pattern of 2arctan(√2/5) ≈ 31.586338° away, and 2arctan(√2) ≈ 109.471221° away.

The triple helix is folded from 3-panel-wide ribbon. Each panel is folded the length of the ribbon at 2arctan(√2) ≈ 109.471221°. The individual triangles are folded in an alternating pattern of 2arctan(√2/4) ≈ 38.931629° away, and 2arctan(√2/5) ≈ 31.586338° toward.

A casual assessment of the triple helix might lead to the assumption that the two angles between which the three helices oscillate, i.e are folded in a repeating pattern of one fold up, and one fold down, etc., are the same angle. They are not. As a consequence, one tetrahelix cannot be nested with another. There is always a gap of approximately 7.356103°, which causes them to spring apart. Fuller called this gap the “unzipping angle”, and thought it might explain the behavior of replicating DNA molecules.

The models of the tetrahelix so far discussed are constructions that result in only the outer shell of the tetrahelix, i.e., a hollow tube with no interior faces. The interior faces can be folded from a separate strip. In the illustration below, two strips of triangles are folded and combined as a double helix that constitutes the surface of the tetrahelix, and a third strip of triangles is folded to constitute its internal structure. The third strip which is enclosed by the other two is is folded at angles of arctan(2√2) ≈ 70.528779° alternately toward and away. Its striking similarity to the structure of the DNA molecule, i.e. a double helix with paired connections, was not lost on Fuller.

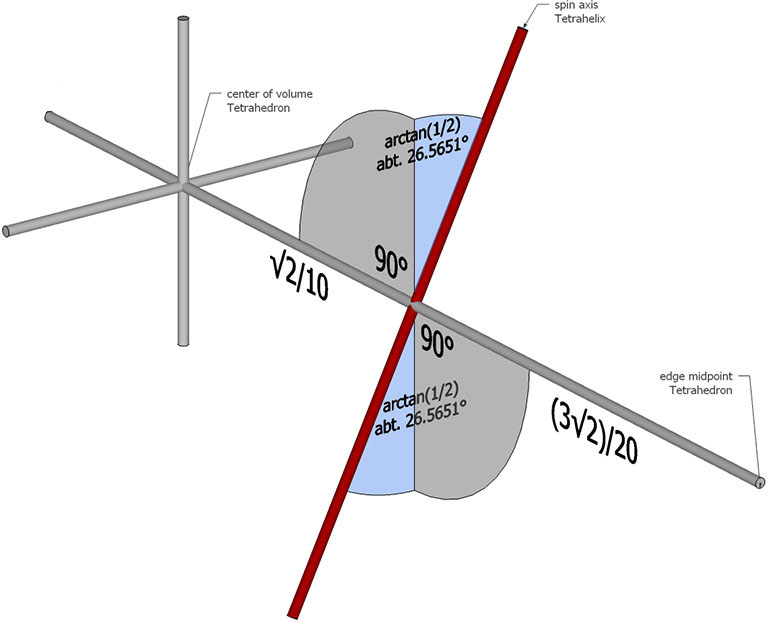

The helical axis does not pass through through the center of volume of any of its constituent tetrahedra. With the edge length taken as unity, the spin axis of the tetrahelix crosses an edge-to-edge axis of each tetrahedron perpendicularly at a distance of √2/10 from its center of volume, and is tilted at an angle of arctan(1/2), about 26.565051°.

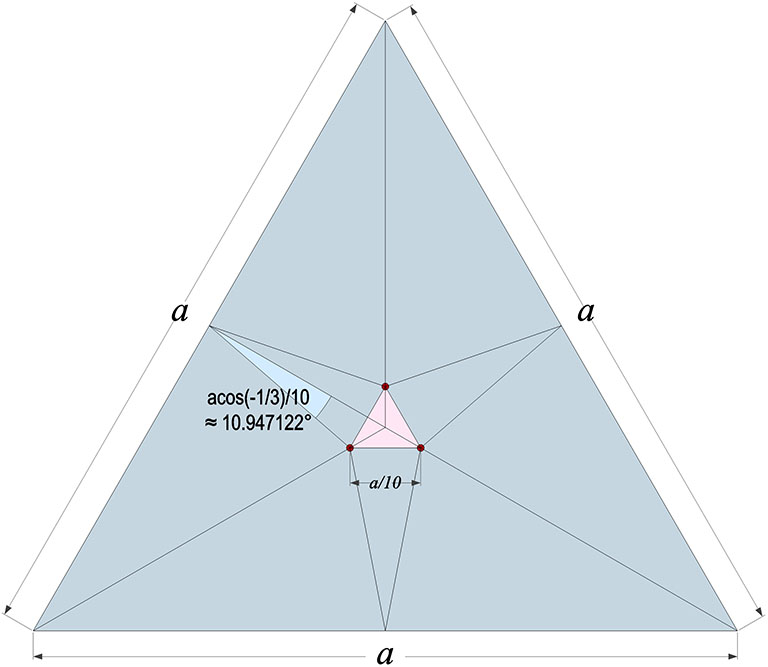

The point at which all possible spin axes pass through the tetrahedron’s faces appears to be precisely arctan(√2)/5, or about 10.947122° off-center along lines drawn from a vertex to the midpoint of the opposite edge. Their points of intersection form an equilateral triangle centered on the face with edge length 1/10th that of the face.

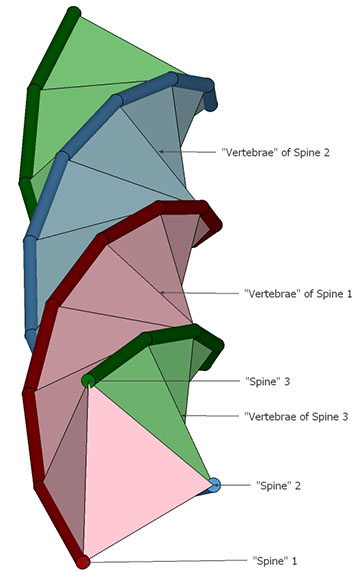

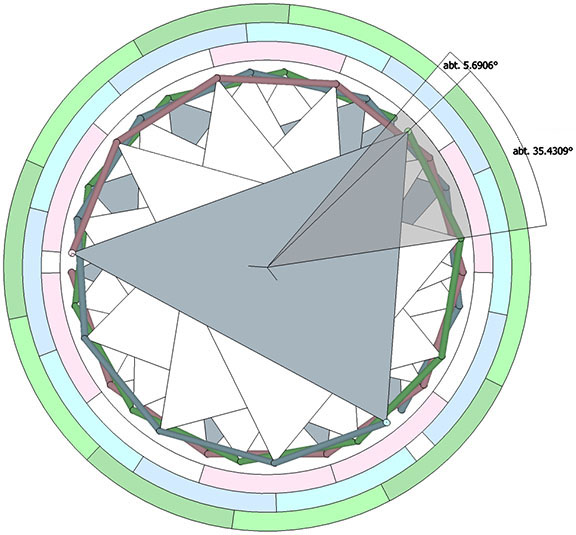

Each tetrahedron is rotated about the helical axis at an angle of arctan(2/√5)+90°, or arccos(-2/3), about 131.810315°, from the one below it. Every third tetrahedron constitutes a “vertebra” of one of the three “spines” of the tetrahelix.

Curiously, the number of tetrahedra is not rationally commensurable with the helical cycle. The helix appears to complete one cycle every 30 tetrahedra, but careful measurement shows the rotation to be just short of 360°. Each vertebra is rotated at an angle of 3arctan(2/√5) – 90°, about 35.430945° from the previous. Ten vertebrae almost, but not quite, complete one 360° cycle. With r being the rotation per vertebra, the difference is 360-(10r) ≈ 5.690553°.

One might assume that one and only one helix may be formed from each of the four faces of the tetrahedron, i.e., that there are four (4) possible helical constructions. Further consideration may allow for clockwise and counter-clockwise helices, making for a total of eight (8) possibilities. Actually, there are twelve (12) unique axes upon which the helix can be constructed.

Each of the twelve axes can be illustrated with a cube placed inside a regular tetrahedron and sized such that four of its eight corners intersect the four faces of the tetrahedron as an equilateral triangle of edge length 1/10th that of the tetrahedron. Each of the twelve axes is described by lines connecting the vertices of the triangle with the center of the cube’s face with which it intersects.

The twelve unique helices alternate between clockwise and counter-clockwise constructions.

Given the fact that the number of tetrahedra is incommensurate with helical cycle, and the fact that its angles are all individually and mutually irrational, the number of configurations possible from serial inside-outing of tetrahedra, including the number of possible orientations of the individual tetrahedra in a fixed coordinate system, may be infinite.