“All structures, properly understood, from the solar system to the atom, are tensegrity structures. Universe is omnitensional integrity”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 700.04

All structures, from the quantum to the cosmological, consist of islands of compression held together by a continuous web of tension. Continuous surfaces and solids are emergent properties of scale. At cosmological scales, the islands of compression are clusters of matter—dust clouds, planets, galaxies, etc.— in which inertial forces (and, perhaps, something called “dark energy”) provide the resistance in opposition to universal gravitation, the continuous web of tension that is mass attraction. At the microscopic level, the islands of compression are atoms and molecules in which radiant energy provides compressive resistance against the electromagnetic and nuclear forces providing the continuous web of tension that binds molecules and atoms together.

Gravity and inertia, the electromagnetic force and electromagnetic radiation, and tension and compression are all as inseparable from one another as the the push and pull of steel spring. Each pair, though often presented as fundamentally distinct phenomena, are really two views of the same thing, like the convex and concave surfaces of the sphere.

“Tensegrity” is a portmanteau of tension and integrity. It refers to standalone structures that would have as much integrity in the vacuum of space as on the earth’s surface. In its purest form, a tensegrity structure consists of isolated rigid elements, struts, suspended in an unbroken web of tension, tendons. Fuller’s geodesic domes constitute a special case of tensegrities, which constitute the more general class, and the way to an intuitive understanding of geodesic domes is to understand tensegrities first.

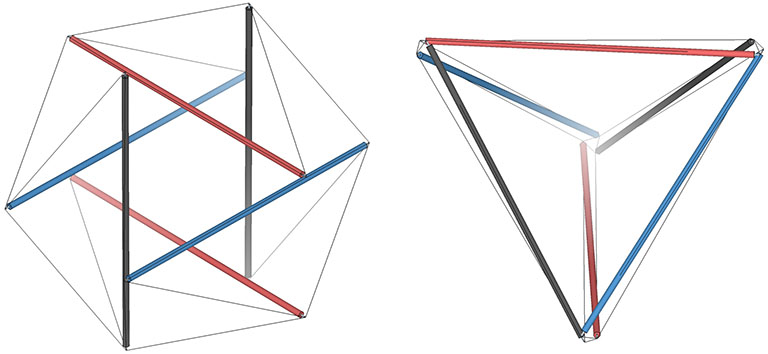

The three basic structural polyhedra, the tetrahedron, octahedron, and icosahedron, can be constructed using these principles. The struts comprising their edges do not touch, but are held in place by the tendons that form a continuous tension web.

Though perhaps not immediately apparent, the three tensegrity polyhedra are transformations of the three tensegrity spheres; the 6-strut Jessen icosahedron, the 12-strut cuboctahedron, and the 30-strut icosidodecahedron.

The transformation involves the clockwise or counter-clockwise torque of the struts. All transformations between the spherical and polyhedral phases are stable. However, the 12- and 30-strut tensegrities are configured as either right- or left-handed and will transform in one direction only. Only the 6-strut tensegrity is ambidextrous; the same spherical condition transforms into either a positive or a negative (right- or left-handed) tetrahedron depending on whether the struts are torqued to the right or to the left. This is in keeping with the unique duality of the tetrahedron. See: The Dual Nature of the Tetrahedron.

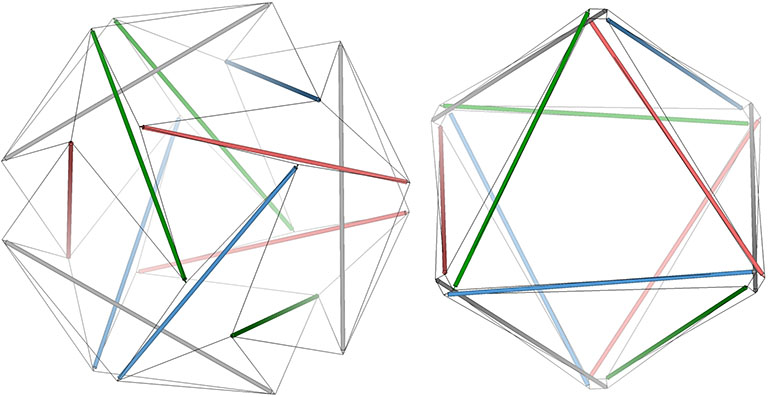

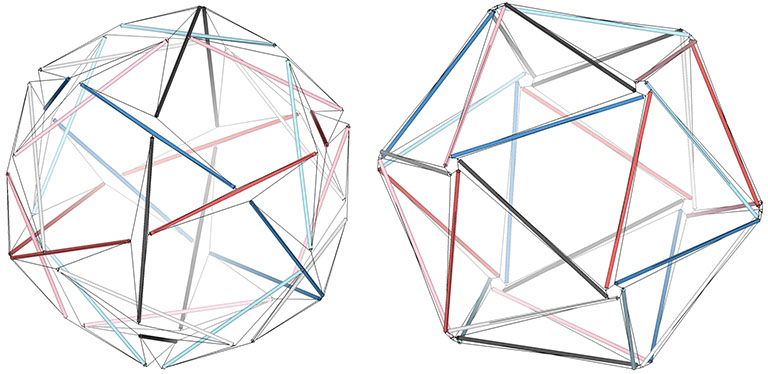

The struts of the three spherical tensegrities are arranged in a pattern of intersecting great circles, or geodesics, each of which divide the sphere into two equal halves: the six-strut tensegrity sphere consists of three intersecting great circle rings of two struts each; the twelve-strut spherical tensegrity consists of four great circle rings of three struts each; and the thirty-strut tensegrity consists of six intersecting great circle rings of five struts each.

This suggests an alternative construction of the tensegrity spheres that has the great circles forming discrete tension loops with the tendons emerging from the strut ends and passing directly under (or through) the cross struts, or “danglers”. The great circles intersect in a stable basket-weave pattern. This strut-and-sling alternative emphasizes the equilibrium state of the spherical tensegrities, as opposed to their more disequibrious, semi-polyhedron states. See: Tensegrity Equilibrium and Vector Equilibrium.

In the transformation from tensegrity sphere to polyhedron, the struts forming the great circles diverge along the path of their danglers. Their paths encircle the polyhedron in zigzag patterns that constitute a geodesic or equatorial “wave” consisting of the primary struts and their danglers.

Note that the great circles of the 12- and 30-strut tensegrities incorporate one dangler each from all of the other great circles. That is, all their great circles intersect each of the others. The great circles of six-strut tensegrity, however, are unique; the struts from only one of the two other great circles serve as danglers in any given great circle. That is, each great circle incorporates all the struts from two and none from the third. This, again, points to the dual nature of the tetrahedron.

In the figure below, the three great circles of the six-strut tensegrity sphere are arranged as follows in its tetrahedron counterpart:

- red-blue-red-blue (red great circle incorporates only blue danglers);

- blue-black-blue-black (the blue great circle incorporates only black danglers);

- black-red-black-red (the black great circle incorporates only red danglers).

The four great circles of the twelve-strut tensegrity incorporate struts from each of the others to form six-strut equatorial bands around the face-to-face poles of the octahedron. Note that the four-strut equatorial bands of the octahedron’s three vertex-to-vertex poles incorporate one strut each from all four great circles.

In the figure below, the four great circles of the 12-strut tensegrity sphere are arranged as follows in its octahedron counterpart:

- red-gray-red-blue-red-green

- blue-red-blue-green-blue-gray

- green-blue-green-red-green-gray

- gray-blue-gray-green-gray-red

The six great circles of the thirty-strut tensegrity incorporate struts from each of the others to form ten-strut equatorial bands around the vertex-to-vertex poles of the icosahedron. Note that six-strut equatorial bands of the icosahedron’s five face-to-face poles incorporate one strut each from all six great circles.

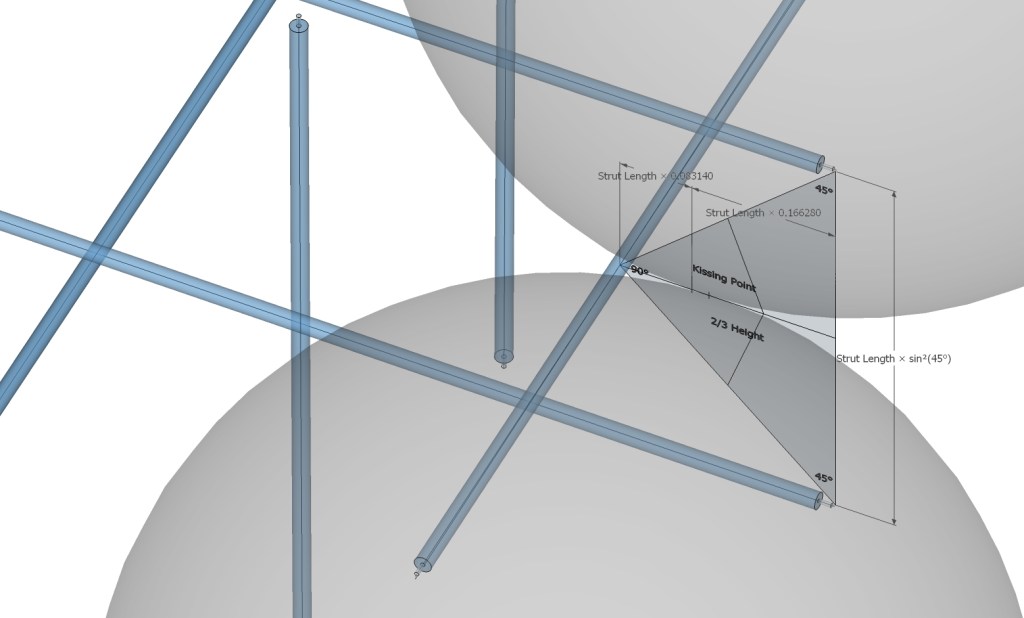

The spherical tensegrities relate to the close packing of spheres. In their “relaxed” states, the strut ends straddle the points of contact between the spheres, what Fuller called the “kissing points.” The kissing points lie on the plane connecting the midpoint of the dangler with the endpoints of its two supporting struts.

In the 12-strut tensegrity, this forms an equilateral triangle whose base edge length (the distance between the supporting struts’ endpoints) equals the strut length multiplied by sin²(30°), or 0.25. The distance from the midpoint of the dangler to the kissing point is approximately 0.066987 times the strut length.

In the 30-strut tensegrity, this forms an 36° 72° 72° isosceles triangle whose base edge length (the distance between the supporting struts’ endpoints) equals the strut length multiplied by sin²(18°), or about 0.095492. The distance from the midpoint of the dangler to the kissing point is approximately 0.03956 times the strut length.

In the 6-strut tensegrity, this forms an 90° 45° 45° isosceles triangle whose base edge length (the distance between the supporting struts’ endpoints) equals the strut length multiplied by sin²(45°), or 0.5. The distance from the midpoint of the dangler to the kissing point is approximately 0.083140 times the strut length.

In their polyhedron states, the strut ends approach the sphere centers. In the twelve-strut tensegrity, the strut ends move from the kissing points to the centers of the six spheres defining the octahedron:

In the thirty-strut tensegrity, the strut ends move from the kissing points to the centers of the twelve spheres defining the icosahedron:

In the six-strut tensegrity, the strut ends move from the kissing points to the centers of the six spheres defining the tetrahedron. Because the six-strut tensegrity can be twisted to form either a positive or a negative tetrahedron, it can oscillate between the two in an uninterrupted transformation.

This unique ability of the tetrahedron to turn itself inside out provides another model of the the sphere-to-space, space-to-sphere oscillations of the jitterbug. If we replace the tetrahedra in the vector model with the six-strut tensegrity, its oscillations between the positive and the negative tetrahedron alternately define the nuclear sphere at the the center of the VE, and the concave VE at the center of the octahedron.

Sphere centers and interstices are identified by tendon loops in the spherical tensegrities. In the figure below, the red polygonal (square) loops of the relaxed 12-strut tensegrity are coincident with the sphere centers, and the yellow triangular loops are coincident with the interstices. See Spheres and Spaces.

If we apply a counter-clockwise torque to a clockwise (and vice versa) 12-strut tensegrity, we force the tensegrity into the unstable* configuration of the cube.

The counter-clockwise torque of a clockwise (and vice versa) 30-strut tensegrity forces it into the unstable* configuration of the pentagonal dodecahedron. Because the 12- and 30-strut tensegrities must always and only be either right- or left-handed, and never both simultaneously, nature disallows these operations.

* “Unstable” may be too strong a word. The tensegrities of otherwise non-rigid (i.e., non-triangulated) polyhedra, like the cube and the pentagonal dodecahedron do hold their shape. However, their strength decreases as the diameter of their vertex loops shrink to points.

Fuller described tensegrities as balloons evacuated of all the supporting gas except for those molecules actively careening around the inside surface on trajectories that are the chords of geodesics. The underlying structure is disclosed by replacing those careening molecules with static struts, and then removing all of the balloon’s skin except for a continuous web of tensile fibers holding the struts in place. A very high frequency tensegrity sphere with all redundancy and non-essential components removed could, in theory, be reduced to molecular bonds, atomic bonds, and ultimately disappear entirely into highly organized quantum fields.

There is another class of tensegrities commonly called tensegrity prisms. The simplest in this class consists of three struts and nine tendons, and has the shape of a triangular prism with the top triangle twisted at 30° from the bottom triangle. Any number of tensegrity prisms are possible. Each is defined by the number of struts which corresponds to the number of sides in the polygon on which is based. In the figure below are tensegrity prisms based on polygons with 3, 4, 5, 6, and 10 sides.

The angle at which the top polygon is twisted in relation to the bottom polygon is a constant and is given by the formula,

90°-(180°/n)

where n is the number of struts, or sides of the polygon on which it is based.

Tensegrity prisms have been combined to form columns, lattices, and complex hyperbolic surfaces. They have also been employed in multi-layered geodesic domes. The possibilities are practically unlimited.

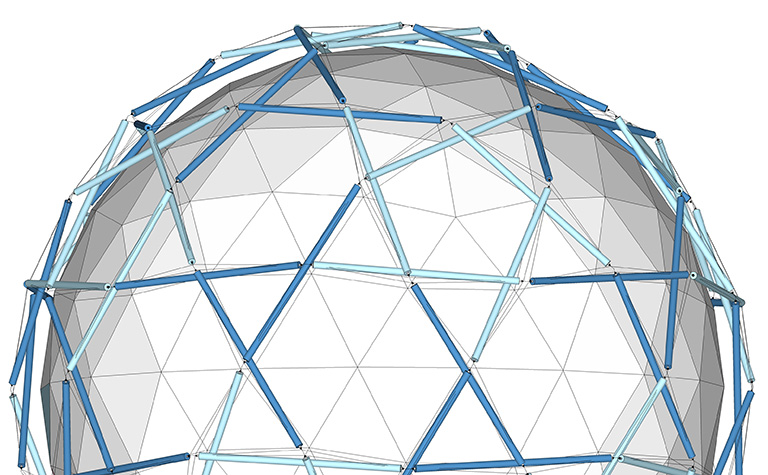

Though building codes assessed Fuller’s geodesic domes as conventional truss networks, they were designed and engineered as tensegrity structures. Redundancies were then added to please the inspectors, and to satisfy the clients’ desire for something that looked substantial. Most were based on the icosahedron, with the 30-strut tensegrity sphere serving as the base model. Regular, triangular subdivisions of the icosahedron create the primary faces of the geodesic polyhedra, all of which (if based on the icosahedron) will have 12 vertices with 5 members, and a larger number of vertices with 6 members. In the spherical tensegrities, these form tension loops of pentagons and hexagons.

All the spherical tensegrities can be reduced to geodesic polyhedra. If we draw in to a point the pentagonal and hexagonal loops in the 120-strut tensegrity sphere above, its 80 triangles enlarge to form the 2F Class 1 geodesic polyhedron.

As frequency and the number of struts increases in the spherical tensegrities, the distance between the struts decreases and the tension and compression elements begin to merge in accordance with the following identities:

dig angle (Φ) = 180°/n

gap = sin²(Φ/2)

dip= 1/2 × sin(Φ/2)

where n = the number of sides in the great (or lesser) circle being assessed. It is the case with most of Fuller’s geodesic domes that the tension web runs through the struts and is therefore implied rather than explicit.

Fuller saw great engineering potential in the understanding of structure as tensegrity:

“As the world’s high-performance metallic technologies are freed from concentration on armaments, their structural and mechanical and chemical performances (together with the electrodynamic remote control of systems in general) will permit dimensional exquisiteness of mass-production-forming tolerances to be reduced to an accuracy of one-hundredth-thousandths of an inch. This fine tolerance will permit the use of hydraulically pressure-filled glands of high-tensile metallic tubing using liquids that are nonfreezable at space-program temperature ranges, to act when pressurized as the discontinuously isolated compressional struts of large geodesic tensegrity spheres. Since the fitting tolerances will be less than the size of the liquid molecules, there will be no leakage. This will obviate the collapsibility of the air-lock-and-pressure- maintained pneumatic domes that require continuous pump-pressurizing to avoid being drag-rotated to flatten like a candle flame in a hurricane. Hydro-compressed tensegrities are less vulnerable as liquids are noncompressible.

“Geodesic tensegrity spheres may be produced at enormous city-enclosing diameters. They may be assembled by helicopters with great economy. This will reduce the investment of metals in large tensegrity structures to a small fraction of the metals invested in geodesic structures of the past. It will be possible to produce geodesic domes of enormous diameters to cover whole communities with a relatively minor investment of structural materials. With the combined capabilities of mass production and aerospace technology it becomes feasible to turn out whole rolls of noncorrosive, flexible-cable networks with high-tensile, interswaged fittings to be manufactured in one gossamer piece, like a great fishing net whose whole unitary tension system can be air-delivered anywhere to be compression-strutted by swift local insertions of remote-controlled, expandable hydro-struts, which, as the spheric structure takes shape, may be hydro-pumped to firm completion by radio control.

“In the advanced-space-structures research program it has been discovered that—in the absence of unidirectional gravity and atmosphere—it is highly feasible to centrifugally spin-open spherical or cylindrical structures in such a manner that if one-half of the spherical net is prepacked by folding below the equator and being tucked back into the other and outer half to form a dome within a dome when spun open, it is possible to produce domes that are miles in diameter. When such structures consist at the outset of only gossamer, high-tensile, low-weight, spider-web-diameter filaments, and when the spheres spun open can hold their shape unchallenged by gravity, then all the filaments’ local molecules could be chemically activated to produce local monomer tubes interconnecting the network joints, which could be hydraulically expanded to form an omniintertrussed double dome. Such a dome could then be retrorocketed to subside deceleratingly into the Earth’s atmosphere, within which it will lower only slowly, due to its extremely low comprehensive specific gravity and its vast webbing surface, permitting it to be aimingly-landed slowly, very much like an air-floatable dandelion seed ball: the multi-mile-diametered tensegrity dome would seem to be a giant cousin. Such a space- spun, Earth-landed structure could then be further fortified locally by the insertion of larger hydro-struttings from helicopters or rigid lighter-than-air- ships—or even by remote-control electroplating, employing the atmosphere as an electrolyte. It would also be feasible to expand large dome networks progressively from the assembly of smaller pneumatic and surface-skinning components.

“The fact that the dome volume increases exponentially at a third-power rate, while the structural component lengths increase at only a fraction more than an arithmetical rate, means that their air volume is so great in comparison to the enclosing skin that its inside atmosphere temperature would remain approximately tropically constant independent of outside weather variations. A dome in this vast scale would also be structurally fail-safe in that the amount of air inside would take months to be evacuated should any air vehicle smash through its upper structure or break any of its trussing.

“In air-floatable dome systems metals will be used exclusively in tension, and all compression will be furnished by the tensionally contained, antifreeze-treated liquids. Metals with tensile strengths of a million p.s.i. will be balance-opposed structurally by liquids that will remain noncompressible even at a million p.s.i. Complete shock-load absorption will be provided by the highly compressible gas molecules—interpermeating the hydraulic molecules—to provide symmetrical distribution of all forces. The hydraulic compressive forces will be evenly distributed outwardly to the tension skins of the individual struts and thence even further to the comprehensive metal- or glass-skinned hydro-glands of the spheroidally enclosed, concentrically-trussed-together, dome-within-dome foldback, omnitriangulated, nonredundant, tensegrity network structural system.“

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, sections 785.03-07, (1975)