In Fuller’s energetic geometry, the great circles of the VE and icosahedron model energy transference and containment. Fuller described them as “railroad tracks” which either move energy from one domain to another, or divert energy into into loops or holding patterns. (See: Great Circles: The 31 Great Circles of the Icosahedron, and; Great Circles: The 25 Great Circles of the Vector Equilibrium (VE).) What interested Fuller in his bow-tie models was their resolution of this idea with the apparent contradiction of no two vectors able to pass through the same point simultaneously. As bow-ties, the great circle energy loops would simply deflect off one another at the vertices, keeping to their own holding patterns without the need to cross paths. All seven of the great circle sets of the VE and the Icosahedron are recapitulated in the bow-tie models described here and in Great Circle Bow-Ties of the Icosahedron. Both, I think, serve as quiet validation of Fuller’s intuitions.

If the paper strips unfolded from a polyhedron suggest wave propagation, or the conversion of mass to energy, the alternative construction of folding paper disks into great-circle bow ties perhaps suggests the inverse, the conversion of energy to mass, a beautiful model for the wave-particle duality of energy.

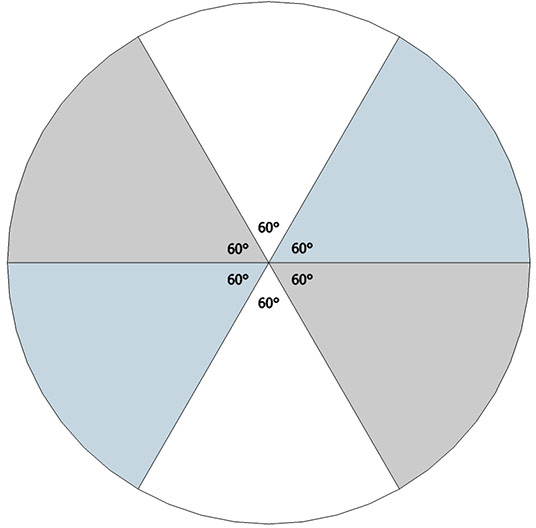

The spherical Vector Equilibrium (VE) is disclosed by the set of 4 great circles described by the 4 axes of spin through the VE’s eight triangular faces. The spherical VE can also be constructed from the folding of the four disks described by these same great circles. These four disks cross each other at 60°, the central angle of each of the VE’s 24 edges.

The disks may be folded along these central angles to form bow-ties and recombined into the same configuration as that formed by the four flat disks. For the bow tie construction of the VE, inscribe its central angles onto four disks as shown, with three fold lines crossing the center at 60°.

The bow tie’s fold lines are the radii of the VE, and the resulting construction discloses the spherical and planar angles shown below.

The VE is constructed from four bow ties. It is no coincidence that the four disks have the same surface area as the sphere they describe, i.e.. four times the area of a great circle. But just as each disk has two surfaces (front and back), a sphere has two surfaces, one convex (the outside) and one concave (the inside). Both are beautifully represented in the bow tie construction of the spherical VE.

In the illustration below, one side of the four disks is exposed in the inside surfaces (colored pink) of the the VE’s eight tetrahedra. The other side (colored blue) is exposed in the inside surfaces of the VE’s six half-octahedra.

The six great circles of the VE, those described by hemispherical rotations about its vertex to-opposite-vertex axes, disclose the spherical rhombic dodecahedron, as well as the spherical cube, and the positive and negative spherical tetrahedron.

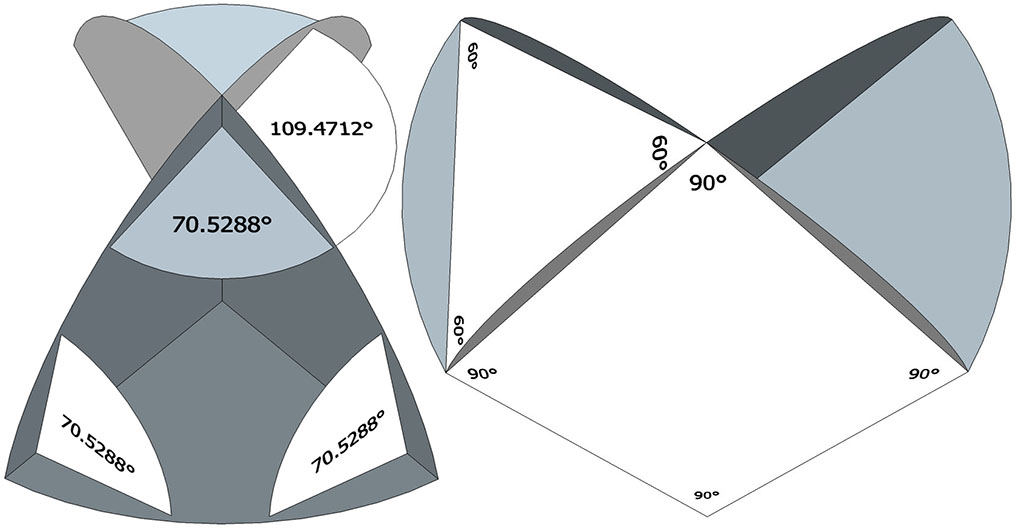

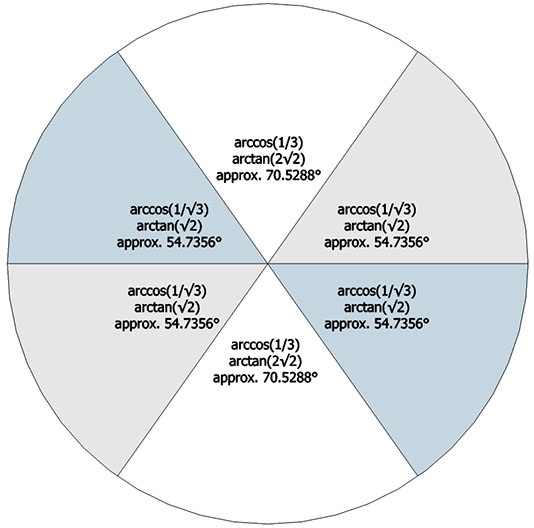

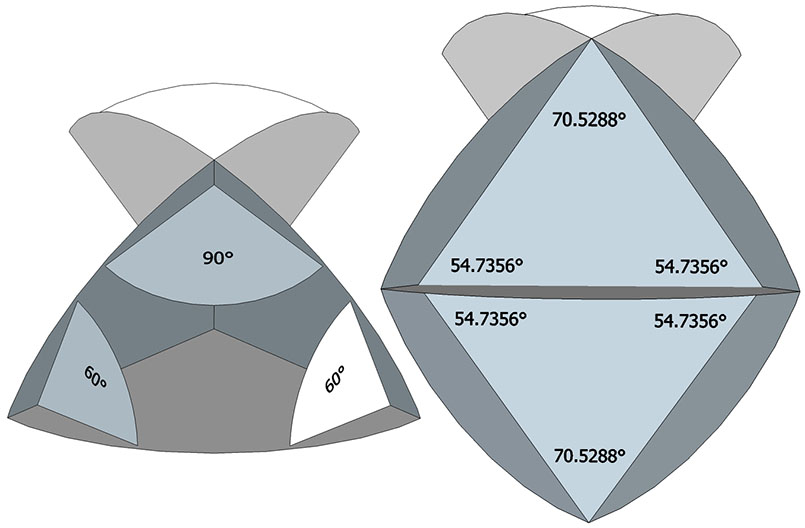

For the bow tie construction of the rhombic dodecahedron, inscribe its central angles onto six disks as shown, with fold lines crossing at arctan(√2) ≈ 54.7356°, and arctan(2√2) ≈ 70.5288°.

The bow tie’s fold lines are the radii of the rhombic dodecahedron, and the resulting construction discloses the spherical angles and planar angles shown below.

The rhombic dodecahedron is constructed from six bow ties.

We can remove the extra arc along the short diagonal of each rhomboid face to further clarify the rhombic dedecahedron. Coincidentally these extra arcs are those which disclose the spherical cube.

The bow tie construction of the rhombic dodecahedron with extra arcs removed is the equivalent of two spherical tetrahedra, the same two tetrahedra, one positive and one negative, disclosed by the diagonals of the spherical cube.

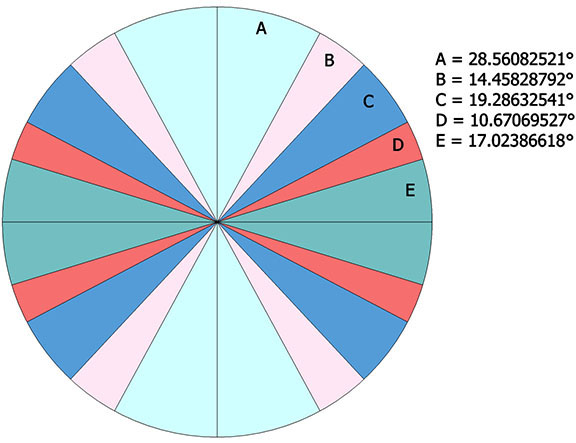

The 12 great circles of the VE, those described by hemispherical rotations about its edge-to-opposite-edge axes, is constructed from great circle disks as follows. The first step is to identify all of the unique surface arcs and calculate their central angles. The central angles are laid out on the circle so that edges which share a common vertex are either adjacent to one another, or can be made so by folding. Each of the four right-angle quadrants is scribed with fold lines at the the following angles in alternating sequences: A ≈ 28.56082521°; B ≈ 14.45828792°; C ≈ 19.28632541°; D ≈ 10.67069527°, and; E ≈ 17.02386618°.

The folding of each of the twelve great-circle disks is rather complex.

The assembly is achieved by 90° rotations about the centers of six octagons arranged, conveniently, on perpendicular axes.

So far we’ve covered the bow tie constructions of the common polyhedra derived from the folding of the 4, 6, and 12 great circles of the VE, the axes of spin through the eight triangular faces, the twelve vertices, and the twenty-four edges. One axis of spin remains, the three running through the VE’s square faces and which defines the spherical octahedron. The three axes are perpendicular to one another and the central angles are therefore all 90°.

The recapitulation of the octahedron though the folding of its 3 great circle disks is not possible. The bow tie construction of the octahedron requires 6 great circle disks, the same number used in the the rhombic dodecahedron. These are folded into two half-circles which are folded again into quarters at 90° to form an L shape. Each edge of the final octahedron is therefore doubled. Note that this doubling is also present in the vector model of the jitterbug when the 24 edges of the VE contract to the 12 edges of the octahedron.

The folded units are then arranged around a common center to form the complete octahedron.

Note that only one face from each of the six disks is displayed. The other is hidden inside the folds. In the vector model of the isotropic vector matrix, the octahedron defines the space between spheres. A space has contact with only the convex surfaces of its adjacent spheres and has no concavity of its own. The exposure of just one face of its great circle disks therefore makes sense for the octahedron.