The third shell of radially close-packed, unit-radius spheres around a common nucleus consists of 92 spheres, a number that Buckminster Fuller did not consider coincidental. (See: Close-Packing of Spheres.) The Periodic Table of Elements, with its 92 stable elements ranging from hydrogen to uranium is after all the close packing of neutrons and protons. Also intriguing is the emergence, in the third shell, of eight new potential nuclei at the centers of the eight triangular faces.

If these eight spheres are added to the second shell’s 42 spheres, they constitute the corners of the first nucleated cube to emerge in the isotropic vector matrix.

And if each is given its own shell of 12 spheres, we can see clearly their nuclear character.

In the close-packed spheres model of the isostropic vector matrix, every sphere is surrounded by twelve others. Whether or not a given sphere in the close-packed array is a nucleus is an arbitrary choice. But the selection of one determines the the regular distribution of all the others.

Connecting the centers of unique nuclei forms a grid of rhombic dodecahedra, fourteen around one, not twelve, as might be expected.

Spherical domains close-pack as rhombic dodecahedra, twelve around one. Nuclear domains close pack like soap bubbles and foams, fourteen around one, and their domain is identical with the solution to the Kelvin problem: How can space be partitioned into cells of equal volume with the least area of surface between them? Fuller noted that the Kelvin truncated octahedron, initially proposed as the solution to the Kelvin problem, encloses nuclear domains.

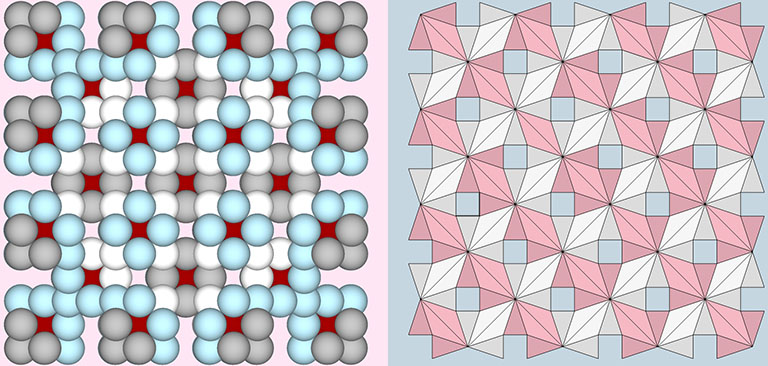

Presently, the best solution to the Kelvin problem is the Weaire-Phelan matrix consisting of Tetrakaidecahedron and Pyritohedron of equal volume. The distribution of nuclei in the isotropic vector matrix coincides beautifully with the Weaire-Phelan matrix, with unique nuclei (shown in red in the figure below) enclosed by pyritohedra, and nuclei whose shells are shared with their surrounding nuclei (shown as pink in the figure below) are enclosed by pairs of tetrakaidecahedra.

This distribution is perhaps easier to conceptualize if we separate out the pyritohedra and the tetrakaidecahedra.

As noted earlier, unique nuclei are distributed on a grid of rhombic dodecahedra. The nuclei whose shells are shared with surrounding nuclei, however, are distributed on a grid of vector equilibria.

If the non-unique nuclei are removed from the matrix, they leave holes that run through the matrix along orthogonal paths. These are likely the same holes seen in the icosahedron phases of the jitterbug.