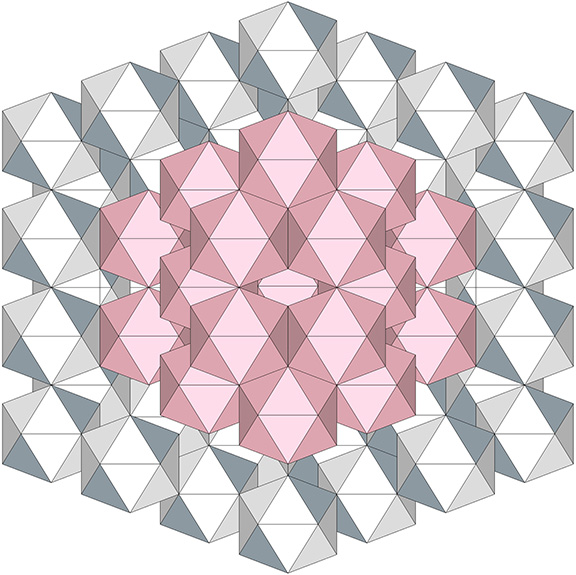

Regular icosahedra will not close pack to fill all space. They can however be edge-bonded to form continuous icosahedral shells which thoroughly isolate the interior from the outside. It is interesting that this recapitulates the 12-around-1 in the close packing of unit-radius spheres, as it does the 12-around-1 arrangement of rhombic dodecahedra in the quantum model of the isotropic vector matrix. This means that the shell volume formula for icosahedra is the same as for the radial close packing of spheres:

Icosahedron Shell Volume = 10F²+2

At the center of the F1 shell (12 regular icosahedra of unit edge length around a common center) is a concave pentagonal dodecahedron, a sort of exploded (inside-outed) version of the vertex-truncated icosahedron.

At its center is an icosahedron with edge length (√5-1)/2, or the golden ratio (φ) minus 1, approximately 0.618034.

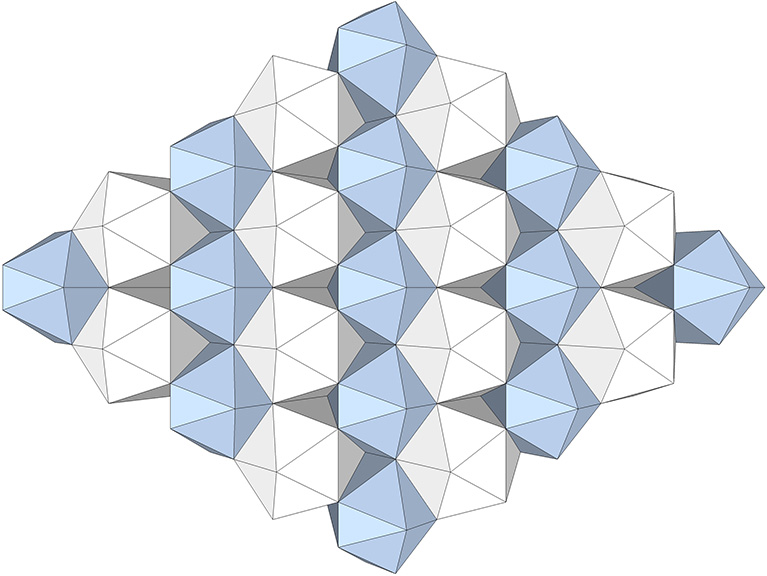

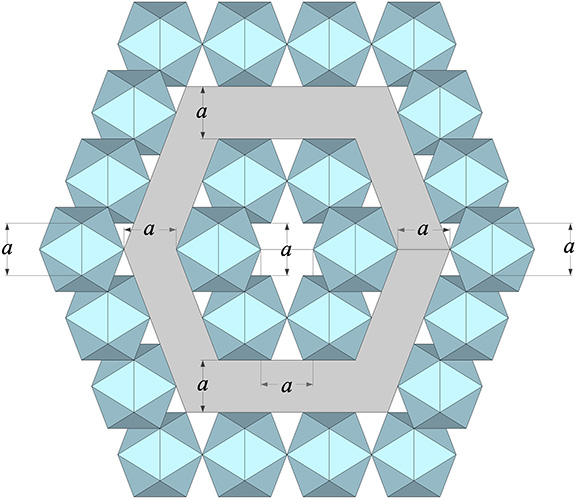

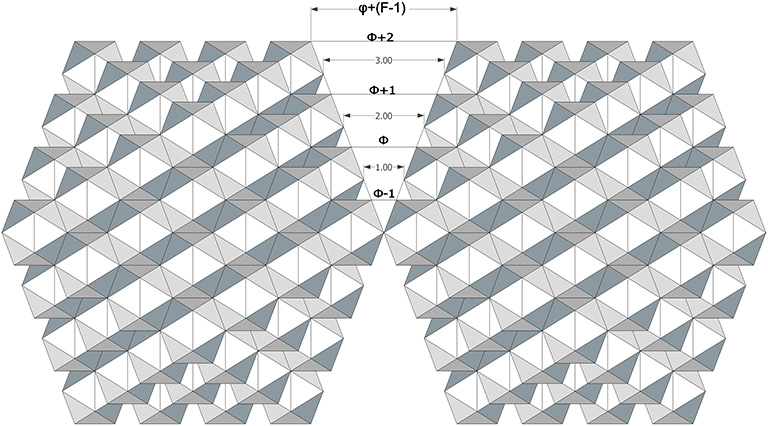

Edge-bonded icosahedra can also form lattices of repeating hexagons.

Note that this lattice is different from the lattices formed in the jitterbugging of the isostropic vector matrix. There, the lattices are formed of regular icosahedra and its space-filling complement. See: Icosahedron Phases of the Jitterbug.

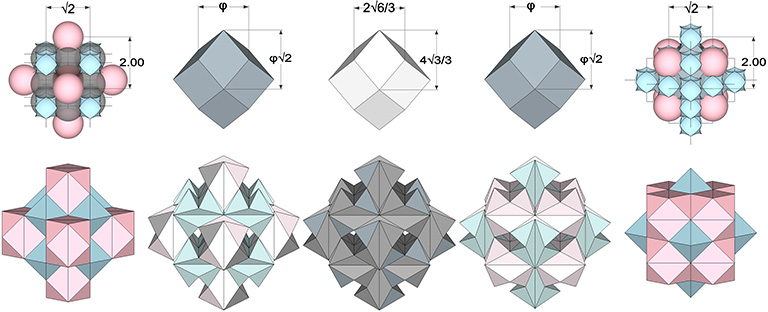

The regular icosahedron and its complement (as well as the Jessen orthogonal icosahedra at tensegrity equilibrium) close pack radially as well as laterally—naturally, as they constitute phases in the jitterbug transformations of the isostropic vector matrix. Note the difference between the close packing of icosahedra as they co-occur in the jitterbug, and the close packing of regular icosahedra around a common center. Here it is 14-around-1, not 12-around-1. Fourteen is the number of faces of the VE, and the number of VEs and octahedra surrounding the central VE in the jitterbugging matrix: six VEs face-bonded to its square faces; plus eight octahedra face-bonded to its triangular faces.

Vector equilibria and octahedra close pack as rhombic dodecahedra that expand and contract during the jitterbug transformation. Maximum expansion coincides with the phase which I call tensor (or tensegrity) equilibrium. It occurs at the precise midpoint of the transformation, when the vector equilibria and octahedra have both transformed into the Jessen orthogonal icosahedron which, not coincidentally, has the same shape as the six-strut tensegrity sphere. (See: Tensegrity.)

The short axis of the rhomboid faces increases from √2 at vector equilibrium, to φ at the icosahedron phases, and to 2√6/3 at tensegrity equilibrium. The long axes increase from 2.0 at vector equilibrium, to φ√2 at the icosahedron phases, and to 4√3/3 at tensegrity equilibrium.

The icosahedron and its complement exchange places twice per cycle as the matrix enters and exits tensegrity equilibrium.

The angles of the rhombic lattice formed from the regular icosahedron and its complement correspond with the face angles of the rhombic dodecahedron and the dihedral angles of the regular tetrahedron, arctan(√2) and arctan(2√2)) or approximately 54.7356° and 70.5288°.

Regular icosahedra can form icosahedral shells of any frequency, but the shells do not nest inside one another. Note further that the shells do not occur as subdivisions of the lattice. That is, the regular icosahedron may form indefinite lattices or definite shells, but never both in the same matrix.

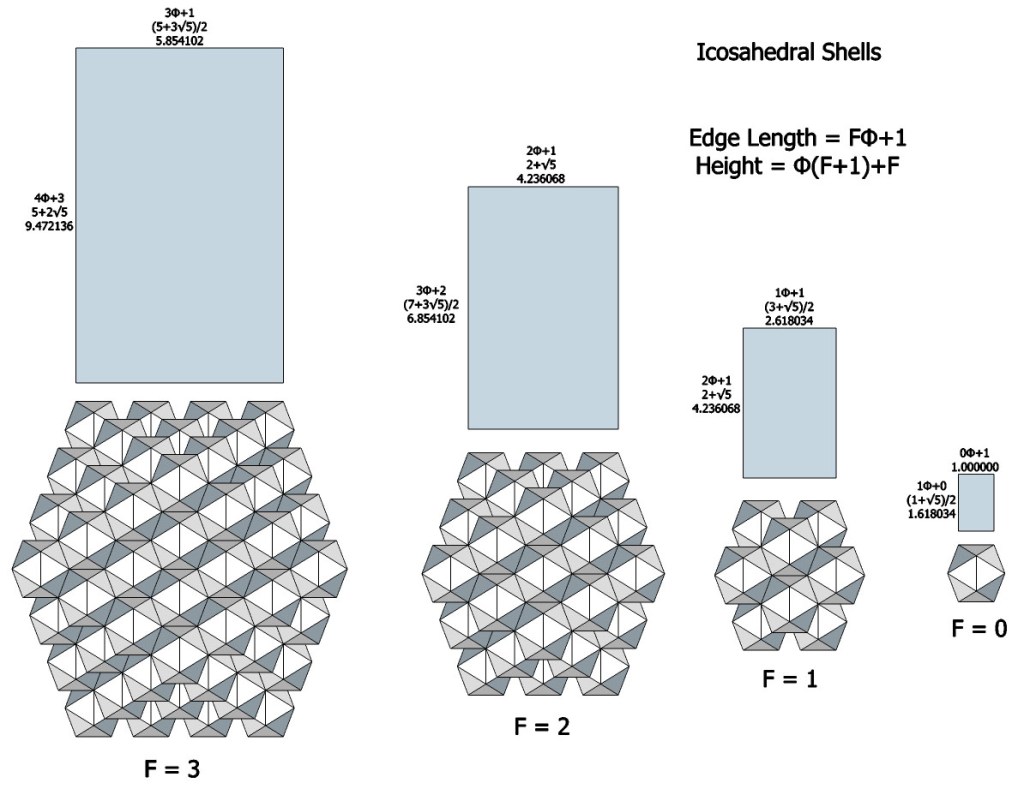

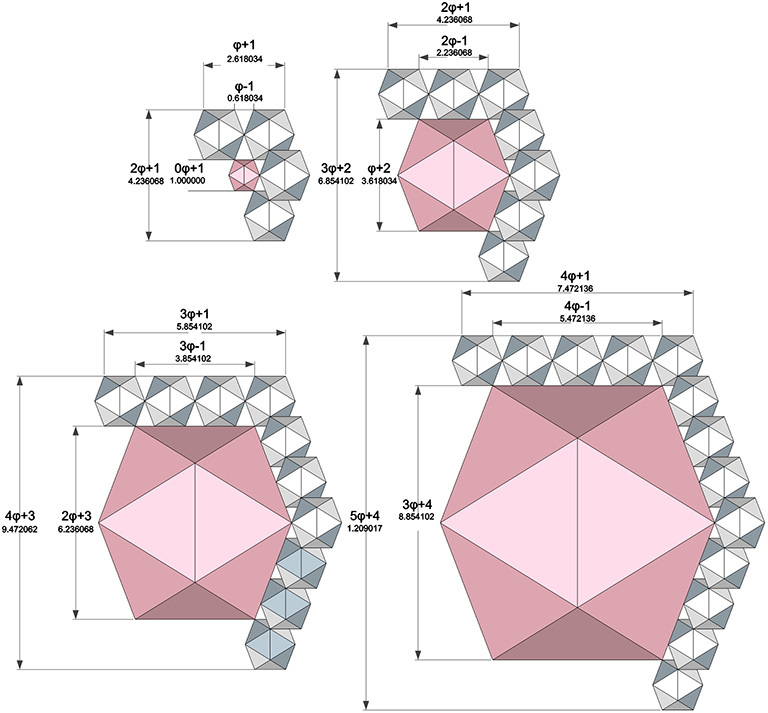

Given icosahedra of unit edge length, the edge length of any icosahedral shell is φ(F)+1, where φ is the golden ratio, (√5+1)/2, and F is the shell frequency. The height of the icosahedron, i.e. the linear dimension of its cubic domain, divided by its edge length is always φ, so the height of any icosahedron shell is φ times its edge length, that is, φ × [φ(F)+1], or φ²F+φ. But since φ²= φ+1, the equation can be rewritten as φ(F+1)+F.

Icosahedron shell edge length = φ(F)+1

Icosahedron shell height = φ(F+1)+F

The height times with width of any icosahedral shell is always the golden ratio

The inside dimensions of the shells follow similar formulas. A regular icosahedron filling the space inside a a shell of frequency F would have the following dimensions:

Interior icosahedron edge length = φF – 1

Interior icosahedron height = φ(F-1) + F

Note the pattern. The formulas for exterior and interior dimensions differ only by the plus and minus signs.

The largest icosahedral shell that can be enclosed within a shell of frequency F has a frequency of F-2. The gap between the two nested shells is always the same of the constituent icosahedron’s edge length. For example, given an edge-length of a for the constituent icosahedra, an F1 shell can fit inside an F3 shell with a gap of a between the F1 shell’s outer surface and the F3 shell’s inner surface.

The F1 shell consists of 12 icosahedra. But if we allow for asymmetry, that is, if we allow the icosahedra to be slid out of alignment and into the cavities between adjacent icosahedra, it is possible to squeeze at least 31 icosahedra inside the F3 shell. The F1 shell is free to rattle around freely inside the F3 shell, but the motion of the 31-icosahedra aggregate seems to be restricted to, at most, just one axis.

You can, of course, construct shells from shells, but the resulting shell would have holes. That is, the interior of the larger shell would not be fully isolated from the outside.

The opening between edge-bonded icosahedral shells is a rhombus whose short diagonal is φ+(F-1).

The study of icosahedron shells may have implications for and resonance with the behavior of cell membranes and other semi-permeable barriers between systems.