“Because the 120 basic disequilibrious LCD triangles of the icosahedron have 2 l/2 times less spherical excess than do the 48 basic equilibrious LCD triangles of the vector equilibrium, and because all physical realizations are always disequilibrious, the Basic Disequilibrium 120 LCD Spherical Triangles become most realizably basic of all general systems’ mathematical control matrixes.”

—R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 901.18

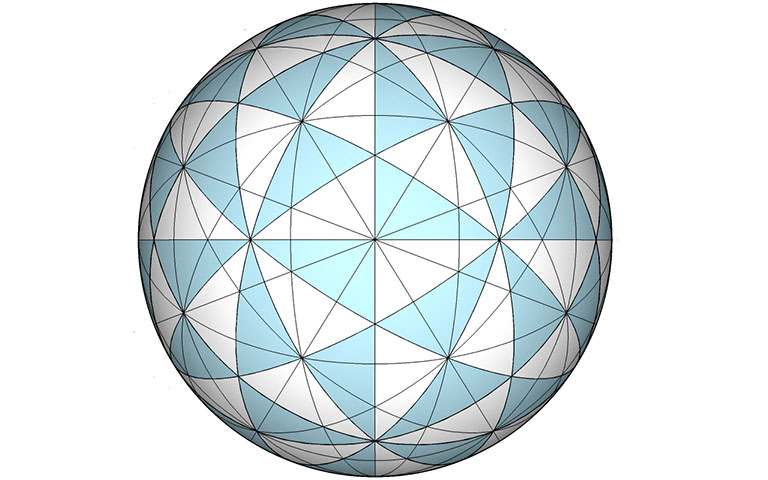

The 15 great circles that define the basic disequilibrium LCD triangle are constructed by spinning the icosahedron on its 15 edge-to-edge axes. It can be shown by spherical trigonometry that further subdividing of the surface would only result in dissimilar triangles. The Basic Disequilibrium LCD Triangle constitutes the lowest common denominator (LCD) of the sphere’s surface, just as the A and B quanta modules constitute the lowest common denominator of polyhedral systems. The trigonometric data for the Basic Disequilibrium LCD Triangle includes the data for the entire sphere and is the basis of all geodesic dome calculations. (See Geodesics.)

The 120 basic disequilibrium LCD triangles represent unit whole subdivisions of the spherical octahedron, icosahedron, pentagonal dodecahedron, icosidodecahedron, rhombic triacontahedron, and VE. (See Icosahedron: Spherical Polyhedra Described by Great Circles.

The sum of all the angles around the vertices of any polyhedral system multiplied by the number of vertices is always 720° less than the number of vertices multiplied by 360°. That is to say that any polyhedral system projected onto the surface of a sphere will have a spherical excess of 720° over its polyhedral counterpart. It is no coincidence that 720° is also the sum of all the surface angles of a tetrahedron.

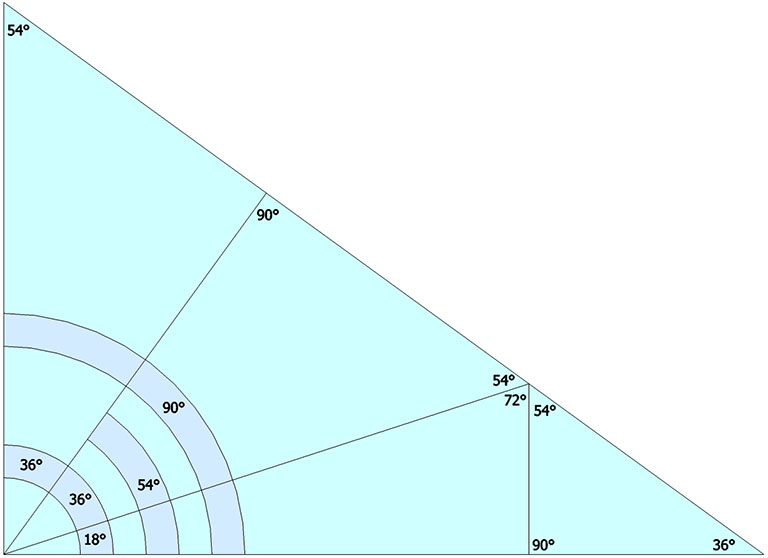

720° distributed equally among the 120 LCD triangles is 6° per triangle. The surface angles of the spherical LCD triangle are: 90°, 60°, and 36°. The surface angles of the spherical LCD triangle projected onto the face of the regular icosahedron are: 90°, 60°, and 30°. Note that all of the spherical excess of 6° is allotted to just one of its angles, i.e., 30° + 6° = 36°.

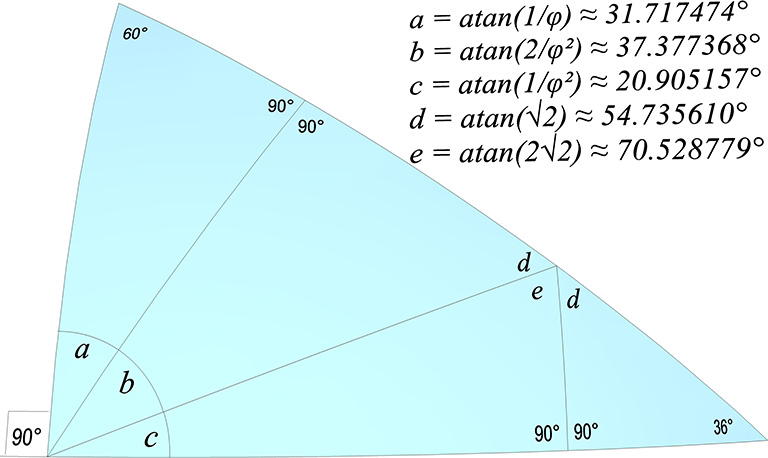

The sets of 10 and 6 great circles of the icosahedron subdivide the LCD triangle into 4 smaller right triangles. Their non-right angles are:

a = arctan(1/φ) ≈ 31.717474°

b = arctan(2/φ²) ≈ 37.377368°

c = arctan(1/φ²) ≈ 20.905157°

d = arctan(√2) ≈ 54.735610°

e = arctan(2√2) ≈ 70.528779°

The angles a, b, and c add to 90° and constitute the LCD triangle’s right angle. The angles d(×2) and e add to 180°.

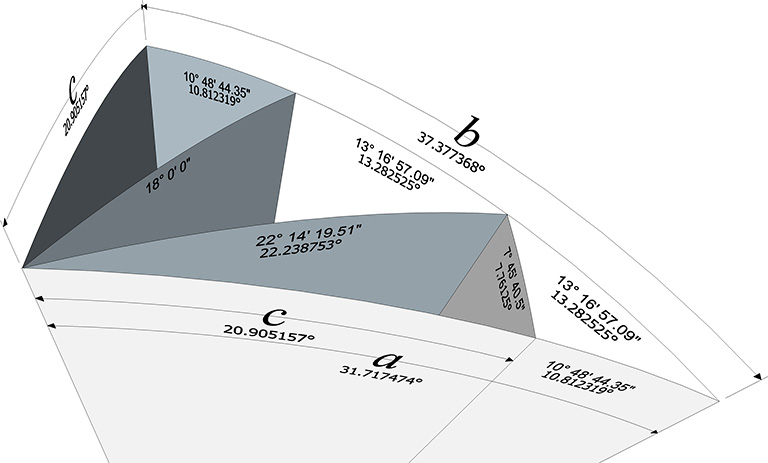

In a surprising and beautiful coincidence, the central angles of the Basic Disequilibrium LCD Triangle add up to exactly 90° and correspond exactly to the surface angles subdividing its 90° corner: atan(φ) ≈ 31.717474° ; atan(2/φ²) ≈ 37.377368″, and; atan(1/φ²) ≈ 20.905157°. It follows that the triangle may therefore be folded along these surface angles to form a tetrahedral cone exactly proportional to that formed from its central angles.

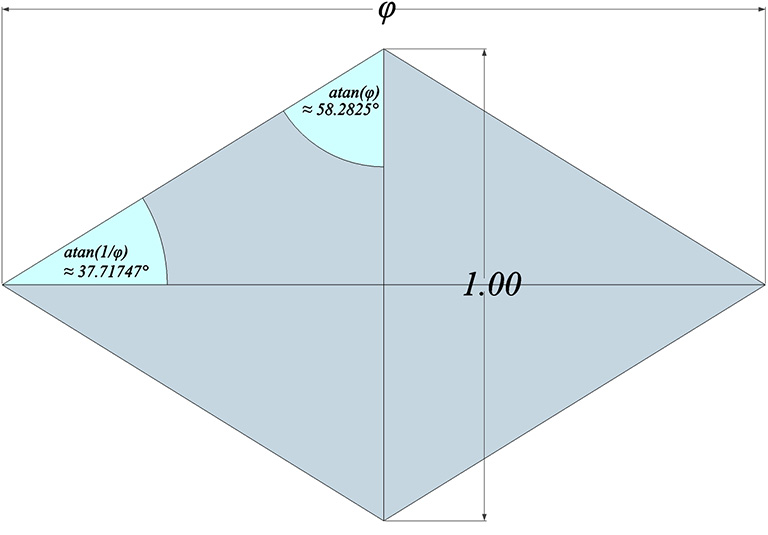

The three angles subdividing the LCD’s 90° corner—the same three angles that constitute the central angles of the LCD’s edges—also relate to the golden rhombus (see The Golden Ratio.) The first angle, atan(1/φ) ≈ 31.71747°, and the other two, atan(2/φ²) ≈ 37.377369° and atan(1/φ²) ≈ 20.905158°, add to atan(φ) ≈ 58.2825°.

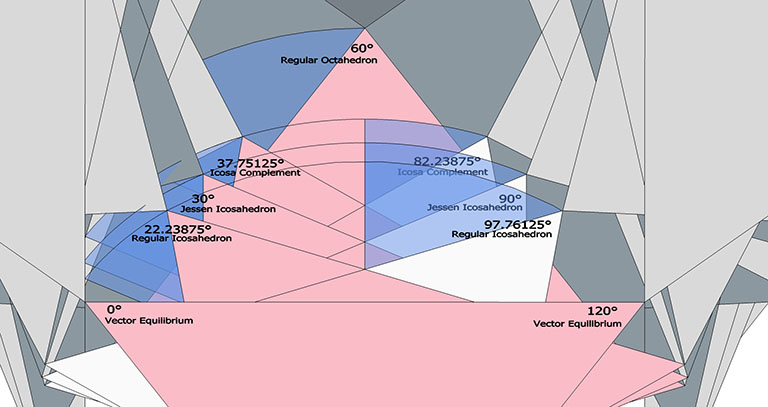

Another surprising coincidence is that the central angles of the interior arcs, 22.238753° and 7.76125° add to 30°, and are equivalent to the angles of rotation that separate the icosahedron phases of the jitterbug.

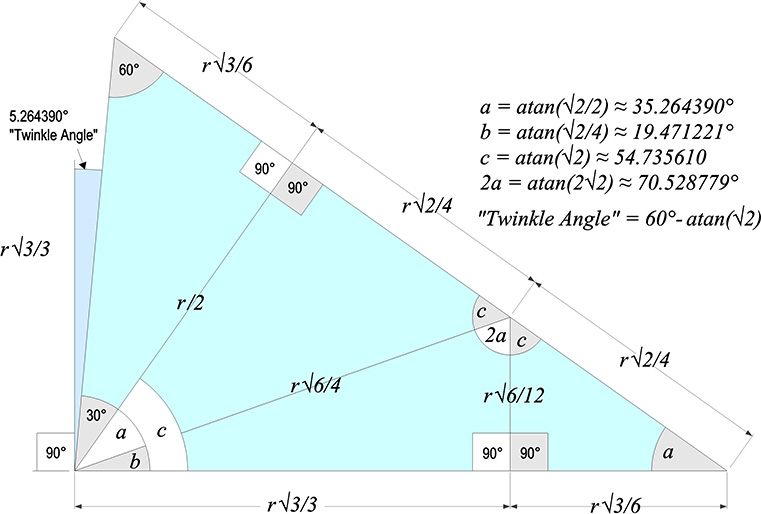

The basic disequilibrium LCD triangle bears a striking resemblance to the unfolded A quanta module. The six degrees of spherical excess are subtracted from the angles in the A quanta module which correspond to the 36° and 90° angles of the Basic Disequilibrium LCD Triangle. In the A quanta module the 36° angle is reduced to to 35.2644° (atan(√/2/2). The 90° angle is reduced to 84.7356° (atan(√2) + 30°), for a difference of approximately 5.264390° which Fuller called the “Twinkle Angle.” The Twinkle Angle’s asymmetry in respect to the isotropic vector matrix is discussed further in The Minimum All-Space-Filling Tetrahedon: “MITE”.

All the other angles of the A quanta module are identical with those of the spherical LCD triangle. The correlation is intriguing. Both are least common denominators—one for surfaces and one for volumes—and both are derived from the basic operational mathematics and constructive geometry of the close packing of spheres.

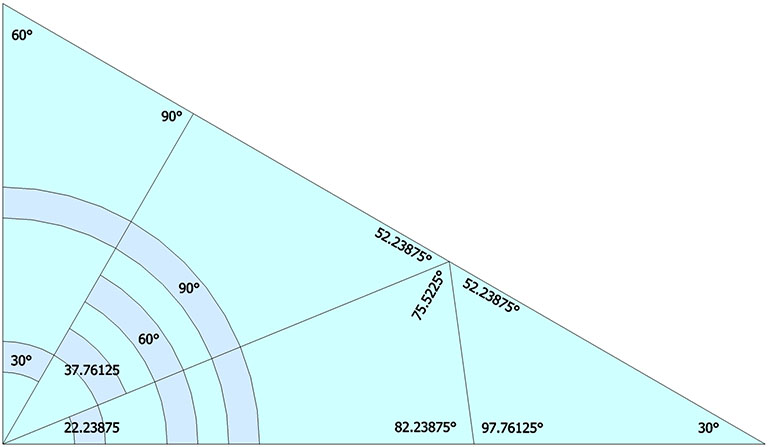

The planar counterpart of the spherical LCD triangle derived from the regular icosahedron is used in most geodesic dome calculations. As already noted, the three corner angles are reduced from 36°, 60°, 90° in the spherical triangle, to 30°, 60°, 90° in the planar triangle. That is, the six degrees of spherical excess is carried entirely by the 36° angle.

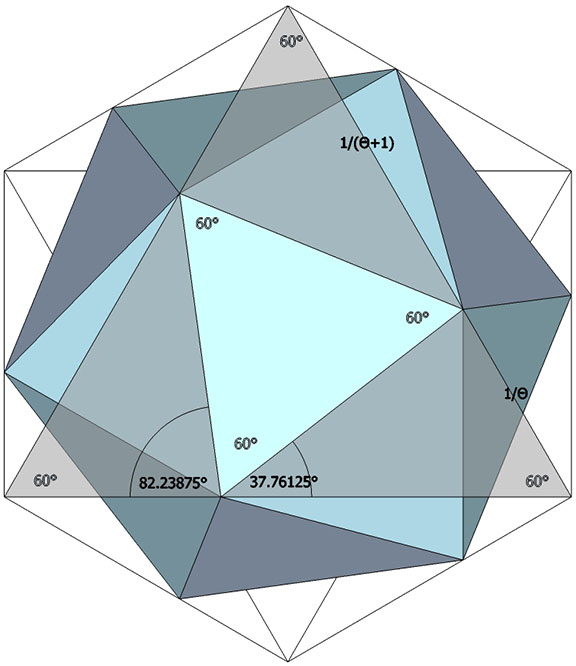

As with the spherical LCD triangle, The coincidence of spherical angles and surface angles also shows up in this planar projection. The central angle of 22.23875° in the spherical LCD is the same as the angle from the base to the the chord of that arc in its planar projection. Three others are sums of the central angles previously noted as coincident with the angles of rotation in the jitterbug: 30° + 22.23875° = 52.23875°; 60° + 22.23875 = 82.23875°; 30° + 7.76125° = 37.76125°; and 90° + 7.76125° = 97.76125°.

The interior angles in the icosahedron projection of the LCD triangle are identical with the rotations of the icosahedron phases of the jitterbug.

The angles 37.76125° (arctan(√(3/5)) and 82.23875° (arctan(√(5/3)) + 30°) also show up in the icosahedron inscribed inside the octahedron. They are the same angles at which the face of the icosahedron is skewed from the face of the octahedron into which it is nested.

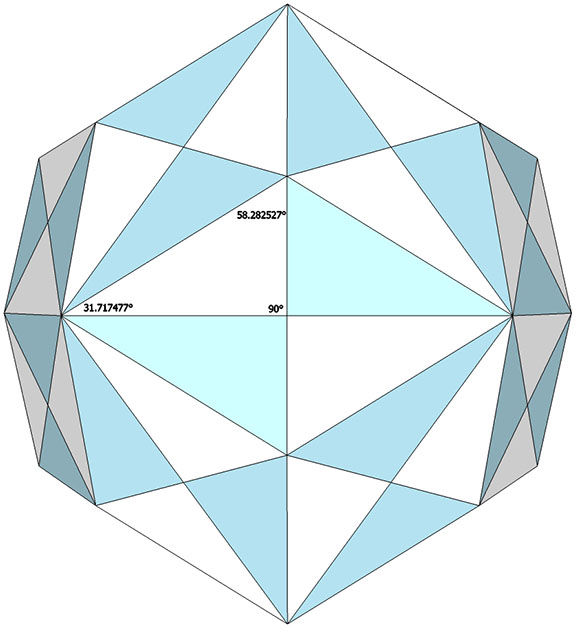

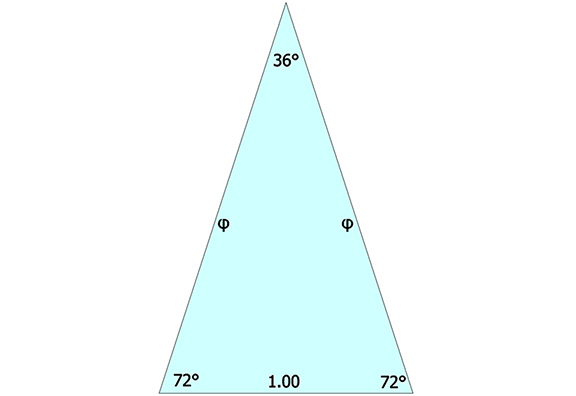

The planar angles of the of the Basic Disequilibrium LCD Triangle may also be derived from the rhombic triacontahedron whose faces are identical with the golden rhombus (see above, and The Golden Ratio.) Instead of subdividing the twenty triangular faces of the regular icosahedron into six identical triangles, we can subdivide the thirty rhomboid faces of the rhombic triacontahedron into four. In this case the planar angles are: 90°, 58.282526° (atan(φ)), and 31.717474° (atan(1/φ)). The six degrees of spherical excess is distributed between the two non-right angles: 4.282526° from smaller of the two (31.717474° + 4.282526° = 36°), and 1.717474° from the larger (58.282526° + 1.717474° = 60°).

Note that both angles are 1.717474° removed from the angles of the planar projection of the LCD onto the icosahedron (30° and 60°) , as well as 4.282526° removed from the angles of planar projection of the LCD onto the pentagonal dodecahedron (36° and 54°) which is described later.

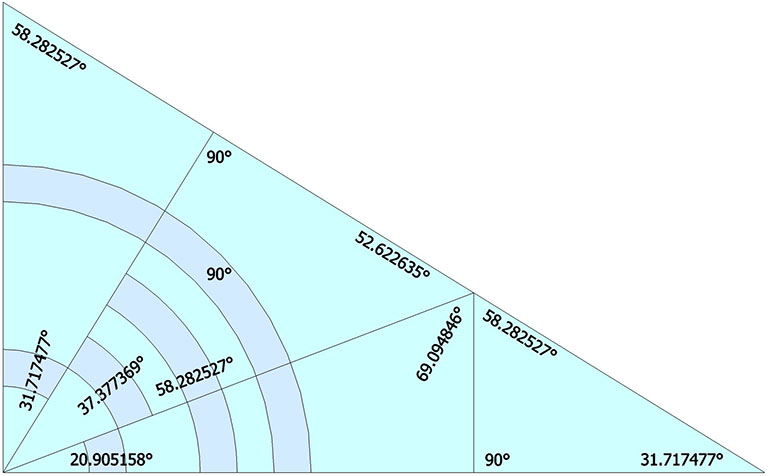

The angles of the planar projection of the LCD onto the rhombic triacontahedron also correspond to the central angles of the spherical LCD triangle. The larger of the two non-right angles of the planar LCD, atan(φ) (≈ 58.282527°), is the sum of 37.377369° and 20.905158°, the central angles of the spherical LCD’s hypotenuse and the smaller of its two legs. The smaller of the two non-right angles in the planar LCD, atan(1/φ) (≈31.717477°) is the also the central angle of the spherical LCD’s base. It is obvious in the planar LCD that these two angles add to 90° as the sum of the angles of any planar triangle must add to 180°. But it is not at all obvious with reference to the spherical LCD triangle alone.

In fact, all of the surface angles of the spherical LCD triangle projected onto the face of the rhombic triacontahedron correspond with the spherical LCD’s central angles. You’ll recognize all but two of the angles in the figure below: 69.094846°, and 52.622635°. These are sums of the LCD triangle’s central angles, 58.622635° + 10.812319°, and 31.717477° + 20.905158°, respectively.

The T and E quanta modules are derived from the projection of the LCD onto the rhombic triacontahedron. See: T and E Quanta Modules.

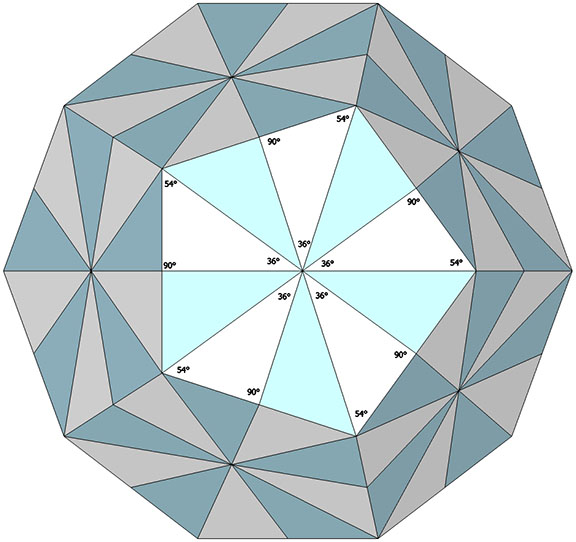

A third option is to derive the planar angles of the of the basic disequilibrium LCD triangle from the pentagonal dodecahedron. Its twelve pentagonal faces are subdivided into ten planar triangles whose angles are 36°, 54°, and 90°.

When projected onto the face of the pentagonal dodecahedron, it is perhaps surprising at this point to discover that all of the angles corresponding to surface angles of the of the spherical LCD triangle are whole rational numbers.

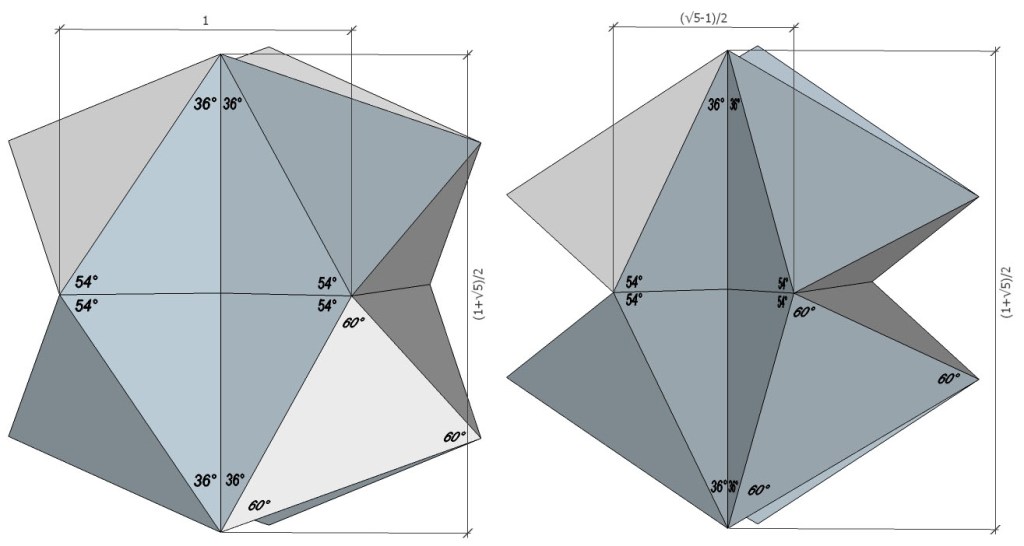

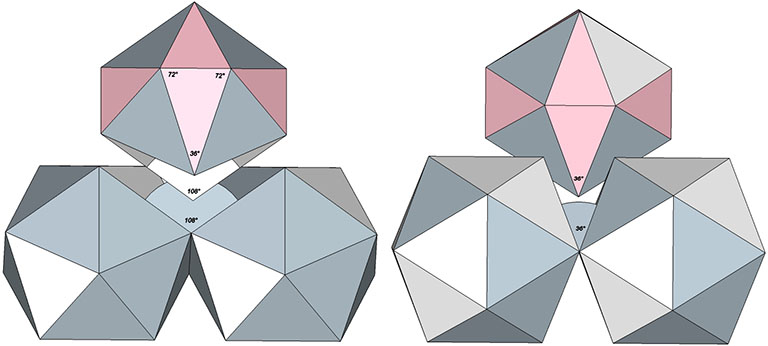

These angles correspond neatly to the face angles of the concave regular icosahedron and its space-filling complement.

The face angles and dihedral angle of the space-filling complement to the regular icosahedron nest with edge-bonded regular icosahedra: 72° and 36°, the same angles, incidentally, of the golden triangle.

The surface angles of the LCD triangle projected onto the surface of the pentagonal dodecahedron match these angles precisely. This and the foregoing suggests an intriguing relationship between the Basic Disequilibrium LCD Triangle and the jitterbug transformations of the isotropic vector matrix. (See also: Icosahedron Phases of the Jitterbug.)

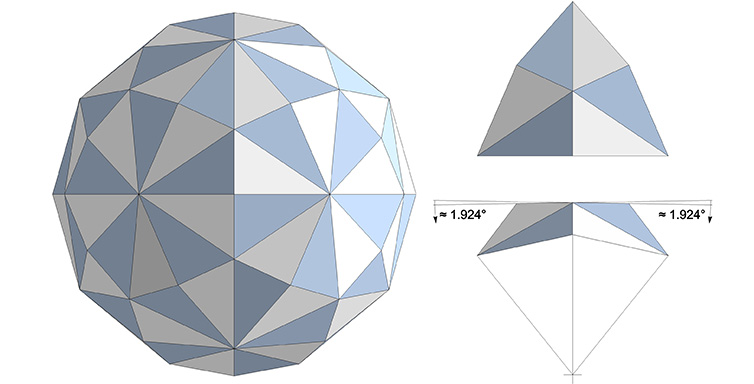

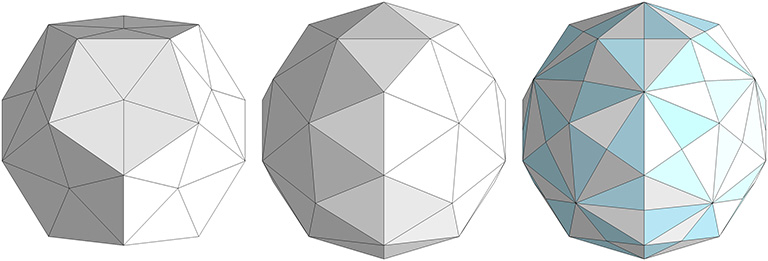

A fourth option is to derive the planar angles of the of the basic disequilibrium LCD triangle from the 60-faceted geodesic polyhedron based on the pentagonal dodecahedron. Each of its 12 pentagonal facets is divided into five isosceles triangles. The shared vertex at the center of the pentagon is then projected outward to the circumsphere radius. (Note: This polyhedron is identical with a 2F Class 2 geodesic icosahedron. See Geodesics.)

Each of the 60 facets of this geodesic polyhedron consists of one positive and one negative LCD triangle bonded on the right angle’s long leg.

We can go one step further and project all the vertices of the LCD triangle out to the same circumsphere radius. On first inspection, this appears to produce a 60-faceted polyhedron with each face consisting of two LCD triangles bonded on their hypotenuse. Closer inspection, however, shows their planes to be rotated about two degrees from the other.