“The geometrical model of energy configurations in synergetics is developed from a symmetrical cluster of spheres, in which each sphere is a model of a field of energy all of whose forces tend to coordinate themselves, shuntingly or pulsatively, and only momentarily in positive or negative asymmetrical patterns relative to, but never congruent with, the eternality of the vector equilibrium. […] Synergetics is comprehensive because it describes instantaneously both the internal and external limit relationships of the sphere or spheres of energetic fields; that is, singularly concentric, or plurally expansive, or propagative and reproductive in all directions, in either spherical or plane geometrical terms and in simple arithmetic.”

— R. Buckminster Fuller, Synergetics, 205.01

The point in conventional geometry is replaced by the sphere in Fuller’s geometry. Vertices are the geometric centers of spheres, and vectors connect sphere centers. There are no continuous lines. Surfaces and volumes are point populations, i.e., close-packed spheres or the vertices that define the sphere centers. The minimum point is defined as a vector equilibrium (VE) of zero frequency, i.e. the nuclear sphere. The shell volume of the zero-frequency VE is give by the shell-growth formula for radially close-packed spheres, 10F²+2, as “2,” i.e., the inside surface, plus the outside surface. Unity is plural and at minimum two.

Every sphere has two surfaces, one convex and the other concave. The concave (interior) surface resists compressive forces while the convex (exterior) surface resists tensile forces.

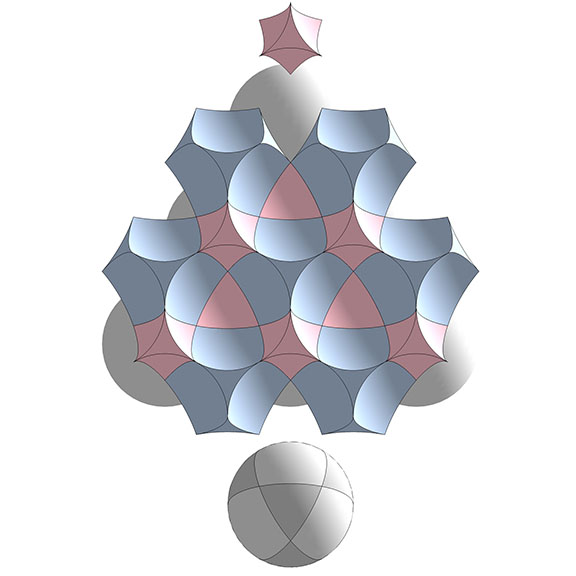

In the following illustration, cutaways of the sphere show the concave interior surface (pink) under compression, and the convex exterior surface (blue) under tension.

These two forces can be modeled as the radials and circumferential vectors of the vector equilibrium (VE). In the following illustration the radials are represented by rigid struts which resist the compressive force provided by the circumferential vectors represented by elastic bands which in turn resist the tensile force provided by the rigid struts.

The tensegrity model clearly represents the inter-dependence of the two forces, with the convex tension represented by continuous tendons, and the concave compression represented by the discontinuous struts.

In the bow tie model, concave and convex are disclosed as opposite sides of the four great-circle disks that comprise the spherical VE. The combined surface areas of the four disks is the same as the surface area of the sphere they describe. In the illustration below, the two sides are distinguished by color, one pink and the other blue.

In the quanta model, the two forces are represented by the integrative A modules and the dis-integrative B modules. The close packed spheres and spaces which exchange places in the jitterbug, are represented by two rhombic dodecahedra, one being the inside-out version of the other.

The first of the two rhombic dodecahedra has at its core a concave octahedron made entirely of B modules. This core is completely enveloped by A modules, first forming a regular octahedron, and then the rhombic dodecahedron. It suggests an implosive, integrative event.

The second of the two rhombic dodecahedra exposes all of its modules, both A and B, on its surface. None are entirely contained by the others, and it suggests an explosive, dis-integrative event.

In the jitterbug transformation of the quanta model, the two rhombic dodecahedra exchange places, suggesting one is the explosive space (the expanding octahedron) which takes the place of the imploding nucleus (the contracting VE). This concept may be more clear if we look at the transformations of the core in isolation from the shell.

The B modules are arranged in arrow-like shapes that point their faces inward in the transformation from VE to octahedron (contracting nuclei), and outward in the transformation from octahedron to VE (expanding spaces). Fuller’s intuitions about the energy characteristics of the two modules, entropic for the B quanta modules, syntropic for the A quanta modules, seem all the more inspired the more deeply we look into the geometry.

In the interstitial model of the isotropic vector matrix (see Spaces and Spheres Redux), the two forces are made self-evident in the literal exposure of the of the concave interior and convex exterior surfaces of the spheres, represented here as blue concave VE “spaces”, gray convex VE spheres, and pink concave octahedra interstices.